It’s a Saturday night in early March, and chef Tarik Abdullah is madly dishing up plates in the kitchen at Bannister in the Central District. At the register, Matt Watson, an MC and hip-hop producer who performs as Spekulation, rings up customers while Jamil Suleman serves plates of chicken-curry sliders to the growing mass of people, a blend of African-American, East Indian, and Arabic artists, families, and neighbors. Before the night ends, filmmaker Aaron Jacob will arrive at the wine bar to DJ.

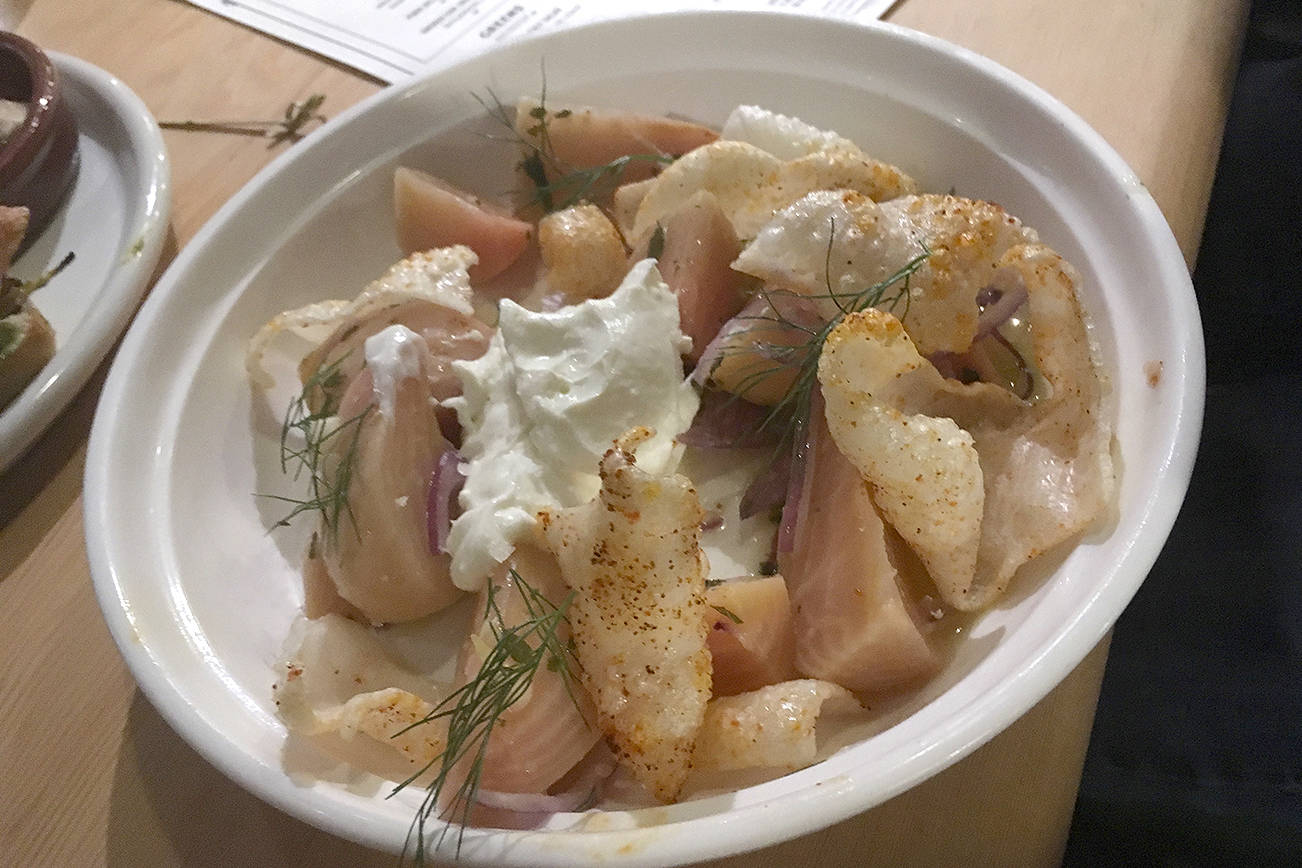

The vibe at this pop-up dinner is celebratory, and the occasion is the first anniversary of “Curry NA Hurry,” a campy hip-hop video, produced by the four friends, that recalls Suleman’s broke college days when he subsisted mostly on curry. The video, featuring cameos from chef Pam Jacob of Pam’s Kitchen, was a modest regional hit, logging 11,000 views. It was also the beginning of a much larger project for Suleman.

A teacher, rapper, and activist, Suleman typically takes on tougher issues than curry: for instance, our failing school system, climate change, and white privilege in songs like “Back to School” and “Dear White Folks.” He’s performed on Russell Simmons’ All Def Poetry channel and has produced singles with local outfits including Ramon Stephens of CHI Music and the EP C.A.T.S.

Curry NA Hurry, though, is important to his mission. The proceeds from the pop-up are helping to fund the Graffiti Village tour that kicks off on March 25 in Bellingham. The two-month tour, which will coincide with the release of Suleman’s forthcoming EP, Araya, will take all four collaborators, plus local award-winning artist Ari Glass and spoken-word poet Jeffon Seely, to states all over the West Coast and Canada. The tour will mix food and entertainment in an effort to promote the idea of a local food economy, in which people would spend their money at, say, a Curry NA Hurry pop-up in their neighborhood instead of at McDonald’s. But the group also has in mind a second, loftier goal: to find—and tell—stories from indigenous people.

“We’re going to have shows, meet up with and interview community organizers and youth workers, visit and link with Native Americans on reservations, and go to National Parks,” says Suleman. “Abdullah will do some pop-up dinners here and there.”

The stories the four collaborators collect will serve as the backbone of Indie Genius Media, a new media company, helmed by Suleman, that will pass the mic to indigenous and independent artists around the world, allowing them an opportunity to tell their stories in their own way—whether through music, spoken word, videos, or visual art. Talking about his new venture, Suleman brings up multimedia juggernaut Vice and the inspiration he’s drawing from its immersive style of journalism and effectiveness in reaching out to millennials. And while IGM is a far cry from the surging international media outlet Suleman hopes to model it on, there is reason to believe that IGM could make some impact, largely due to the talents of his collaborators.

Watson in particular has shown a kind of sixth sense when it comes to viral content. His first brush with Internet fame came after he was fired for posting snarky comments to his Bitter Barista Twitter handle. A book followed. Always happy to instigate through his production skills, Watson later found a wide audience for his remix of a Marshawn Lynch soundbite, and saw his track “’Bout That Action” rack up hundreds of thousands of views and earn notice from the NFL and national news. Abdullah had some time in the spotlight as well, appearing last year on ABC’s The Taste with Anthony Bourdain; he currently makes videos for Vice while not hosting wildly popular pop-ups or volunteering his time to teach south-side kids how to cook.

For his part, Suleman hasn’t gained a national audience, but he has proven an effective organizer. As a mentor for The G.O.O.D. Girls and B.A.D. Boyz program, he brought together kids from Rainier Vista—mostly immigrants and refugees from East Africa—and empowered them to create their own songs and music videos, eventually culminating in a festival in Rainier Valley’s Central Park.

He is also a dogged performer. In the past month alone he has performed at a Syrian refugee benefit at Hollow Earth Radio, the Vera Project, and a Bernie Sanders rally in addition to hosting the Curry NA Hurry pop-up. On March 27 he will put on a benefit for the Graffiti Village tour at the Crocodile before hosting yet another Curry NA Hurry pop-up at his home in the Mount Baker Lofts on March 30.

He is clearly a man on a mission— a mission that extend beyond IGM’s current project.

“It’s a movement of socially conscious people, young people of color, immigrants, children of immigrants, refugees, people with one foot in and one foot out, one back home and one in America,” he says. “And we’ll have great music and camera work. We want to help our folks get attention without objectifying.”

Suleman is the perfect vessel for those who feel like outcasts due to their cultural or ethnic background. As a Muslim-American born to East Indian parents from Africa, he knows what it’s like to get attention for the wrong reasons, or to get no attention at all. Though he was born in the United States, his family struggled to assimilate. It was hip-hop that saved him—“not the mainstream stuff,” he says, “but the culture of hip-hop.”

He is now paying that forward, using hip-hop and spoken word to help others: not just indigenous folks on his tour, but the kids he works with in Rainier Vista as well as youth in prison—again, mostly refugees, who he feels are being failed by the system, by the schools. As part of the Creative Justice mentor program (a King County 4Culture program), he’s helping kids in jail record a full-length hip-hop album.

Education is clearly a topic that gnaws at him. In fact, he wrote two rap songs addressing systemic problems in schools: one called “Blame College” (with the accusation “They sold us all a dream/A life full of debt and misery”) and one about last summer’s teachers’ strike that takes on everything from overtested kids to underfunded schools.

The tour is a continuation of everything he’s been doing for the past few years—specifically, using his art to make the world a better, more inclusive place. “Politics are only going to get us so far,” Suleman says. “But music and food are universal.”