Fratres was a surprise—a shock, even—for a naive grad student in music to discover in 1988. Though by then we’d more or less stopped believing that Schoenberg-style twelve-tone composition or its later refinements were the One True Path, it was still an eye-opener—or ear-opener—to hear a piece so assured, so principled in its eschewal of surface complexity.

Even though it’s scored for the common combo of violin and piano, and even though its form is perfectly simple (inventive variations on a largely triadic chord progression, essentially the passacaglia form we’d all studied in music-theory class), Fratres was—is—like nothing I’d heard. Its extreme contrasts between intensity and quiescence leave expectations unmoored. In its severity and purity, it evokes the Middle Ages without sounding at all like that era’s music; it’s not mere pastiche, a time-travel tourist jaunt to a musical renaissance festival. In fact, its chugging sewing-machine patterns for violin seem to be lifted straight out of a Vivaldi concerto from centuries later.

How does it do this? “Chord progression” is not even an idea applicable to medieval music, whose conception and construction were entirely linear, but somehow Fratres suggests medieval architecture. Gonglike bass notes for piano, followed by stillness, separate the variations; these periodic emptinesses suggest space, open archways, stone pillars, with each variation a separate cell—a monastery, perhaps. The title, Latin for “brothers,” reinforces the reference.

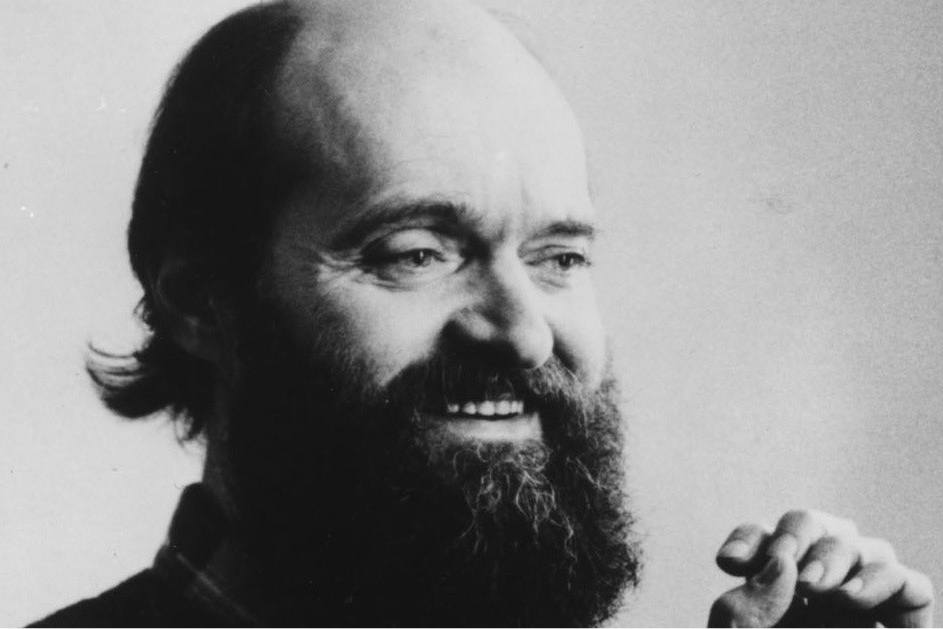

The composer is Arvo Pärt, and the 1984 ECM New Series recording that shook me up, with violinist Gidon Kremer and pianist Keith Jarrett, was his introduction to a far wider audience than he had yet reached in his native Estonia, then part of a Soviet Union whose doctrinaire view of art was slowly thawing. But Pärt’s relative isolation had enabled him to develop a distinctive, even revolutionary voice, backed by a compositional technique of his invention dubbed tintinnabulation: a way of deploying the notes of a scale against the notes of a chord to create a subtly shifting interplay of dissonance and consonance. This technique, plus the courage to use notes sparingly when complication was the fashion, resulted in works of pared-down eloquence and, for many, spiritual profundity in an age when the gap between questing composers and reticent audiences often seemed unbridgeable.

Pärt’s music has bridged it; now 81, he’s the single most frequently performed living classical composer of recent years. Saturday night at On the Boards, violinist Luke Fitzpatrick, cellist Rose Bellini, and pianist Brooks Tran will perform Fratres and other chamber music of his—works that, like Fratres, captivate out of all proportion to the economy of their material. The solo string line in Spiegel im spiegel (“Mirror in the mirror”) follows a completely schematic path: A simple scale rises and sinks in long notes of absolutely even duration, lengthening one note at a time at each end upon each repetition. Pure major chords, these too in an unvarying rhythm, make up the background piano part. The piano piece Für Alina is even sparer: 15 bars and a tiny handful of stemless notes that look like a pinch of poppy seeds sprinkled on the page. The piano solo Variationen zur Gesundung (“Healing”) von Arinuschka further explores the meditative properties of non-intricacy—never more than one note at a time in each hand—while Mozart-Adagio opens up the texture of a Mozart piano sonata’s slow movement by distributing its notes among three instruments and adding discreet, moody commentary.

The feeling of timelessness in Pärt’s music applies to both its echoes of the past and to the trancelike experience of listening to it. (His quantities of liturgical choral works share these qualities; sample those this weekend, too, as Cappella Romana hosts a four-day Pärt festival in Portland.) As Fitzpatrick puts it, “There is a haunting, expressive quality to his music that is difficult to describe in words. He is able to achieve and evoke so much with very minimal musical material. Beyond that, Pärt also does something to the experience of time for both the listener and performer that is very special. Time seems to slow down and expand.” On the Boards, 100 W. Roy St., ontheboards.org. $20. 7 p.m. Sat., Feb. 12. gborchert@seattleweekly.com