In July 1937, a new play hit the boards of the Metropolitan Theatre on University Street. • It was entitled Power, and it told the story of the Tennessee Valley Authority, the massive dam and irrigation project built under the auspices of President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s New Deal programs. • It had, a reviewer in the Seattle Daily Times sniffed, “the subtlety of a sledgehammer and the restraint of a groundswell,” with musical numbers that featured high-voltage couplets: “All up and down the valley, they heard the glad alarm,” one song went. “The Government means business, it’s working like a charm. Oh, see them boys a-comin’, their Government they trust. Just hear their hammers ringin’, they’ll build that dam or bust!”

To add to the fanfare of opening night, Seattle City Light lent the production company several large transformers to adorn the stage, and a favorable audience packed the seats and cheered on the dam’s construction. It’s no secret that the public had simpler demands of their entertainment in the days before Marvel Studios, but the notion of Seattleites packing a 1,600-seat theater to watch a musical about public infrastructure may seem to the modern reader to verge on parody.

However, the excitement for Power in Seattle speaks to the populist fervor many Americans were feeling during the 1930s. As this fervor pertained to electricity, New Dealers were adamant that the people would best be served if electricity was produced and distributed by government-run utilities as opposed to private power trusts—a debate not unlike today’s fight over whether medical insurance should be a service provided by public or private entities.

In 1930, 10 companies owned 75 percent of the United States’ electrical supply. Leading those companies was a who’s-who of American capitalism: John D. Rockefeller Jr., J.P. Morgan Jr., Samuel Insull. Typically, favorable state governments would grant these trusts exclusive access to rivers that they’d dam to generate power—crony capitalism wrapped in a free-market guise.

The Pacific Northwest, and Seattle in particular, had long been ahead of the curve when it came to busting this system. The citizens of Seattle got into the public-power business in 1890 when the city created the Department of Lighting and Water Works, the precursor to Seattle City Light. The city began construction of its first power-producing dam in 1902. In many ways, what Roosevelt had in mind would take the public-power model formed in Seattle, Tacoma, and other progressive cities to a massive scale, and plays like Power, written for the Federal Theatre Project of the New Deal’s Works Progress Administration, would help sell the public on it.

“People will say it’s propaganda,” WPA director Harry Hopkins told the cast following the first production of Power, according to Federal Theatre historian Hallie Flanagan. “Well, I say what of it? If it’s propaganda to educate the consumer who’s paying for power, it’s about time someone had some propaganda for him. The big power companies have spent millions on propaganda for the utilities. It’s about time that the consumer had a mouthpiece. I say more plays like Power and more power to you.”

And while the play focused on the Tennessee Valley Authority, there’s little doubt that the Seattle audience had another project in mind that dwarfed both City Light and the TVA: the Grand Coulee Dam, under construction as the chorus sang.

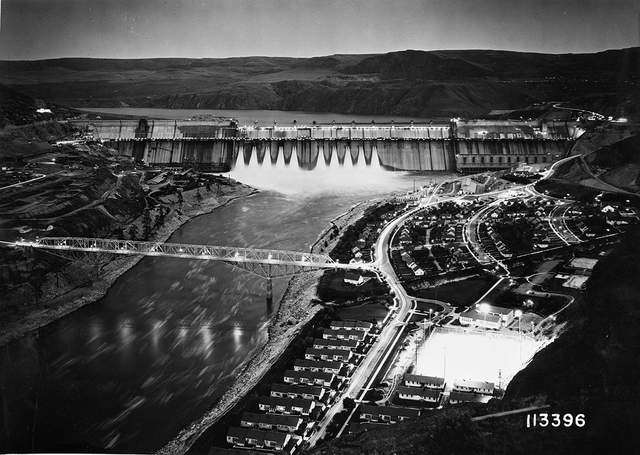

Four thousand feet wide at its crest and 550 feet tall at its lowest bedrock, the dam in central Washington was being billed as the largest structure ever built by man. The enormous amount of potential energy created by restraining one of the great rivers of North America would spin turbines that pumped electricity onto a grid owned and operated by a new federal agency called the Bonneville Power Administration, headquartered in Portland. The electricity would cost a fraction of what private-owned utilities sold it for, a fact touted by New Dealers as proof that the government took better care of the people than the free market did. Beyond the power, the dam would also create a reservoir large enough to irrigate 2.5 million acres of dry Central Washington scrubland, potential homesteads for the hordes of dispossessed Dust Bowl farmers then wandering the land; the reservoir itself would measure 150 miles long, stretching all the way to the Canadian border.

The Government means business, and how.

It was into this tableau—of Rockefeller wheeler-dealers vs. Roosevelt New Dealers, of wasteland imagined as farmland, of unabashed propaganda being staged to packed playhouses—that Woody Guthrie would enter, driving a busted up Pontiac. It was 1941, and the folk singer was 28.

Much as the musical Power made the TVA case through song, the BPA wanted to produce a film documentary explaining the benefits of the Grand Coulee Dam and the Bonneville Dam farther downstream. In search of someone who could write songs on the theme, BPA public information officer Stephen Kahn reached out to Alan Lomax, the ethnomusicologist wunderkind at the National Archives in Washington, D.C. Woody Guthrie wasn’t yet famous, but he’d impressed a lot of heavy hitters in the folk scene. Lomax, 26 at the time, would later say he nearly jumped through the line to recommend the folk singer.

Kahn reached out to Guthrie about the job. However, as Kahn would later tell it, Guthrie hadn’t yet been hired when he showed up unannounced in the Portland offices carrying a guitar. Still, recognizing an opportunity, Kahn arranged an audition then and there with the agency’s administrator. Kahn told him to just sing, not talk. “If you talk, you’ll lose the battle.”

About 30 minutes later, he walked out with the job: a one-month stint as an “informational consultant” for the Bonneville Power Administration.

Guthrie, who would become, arguably, the most influential folk singer of the 20th century, had a particularly fortuitous relationship with the Pacific Northwest throughout his career. In one trip through the region shortly after his employment with the government, he and Pete Seeger stayed with Ivar Haglund in Seattle, and Seeger claimed the duo taught Ivar the old folk tune “Acres of Clams,” which would later become the name of Ivar’s famous restaurant. It was also in Seattle that Guthrie and Seeger learned the word “hootenanny,” which they brought back to New York and popularized as a term for rowdy, folky get-togethers. Guthrie opens his semifictional autobiography Bound for Glory on a freight train headed for Seattle; there’s no evidence he ever actually hopped a train to our city, but the passage shows his affinity for the place.

However, none of these experiences compared to his brief time with the BPA, which would prove one of the most fertile months of the prolific songwriter’s career, and leave an indelible mark on our region’s music history.

He was all but forced to make music. One term of his employment was that he was required to produce a song a day—weekends not included—which his boss Kahn justified by saying it was comparable to Hollywood’s requirements that screenwriters turn three pages a day into the studio. Guthrie came away with 26 songs, many of which turned out to be among his most enduring: “Roll On, Columbia,” “Pastures of Plenty,” “The Grand Coulee Dam.”

Guthrie’s son Arlo Guthrie told documentary filmmaker Michael Madjic that the project was life-changing for his father. “He saw himself for the first time as being on the inside of a worthwhile, monumental, world-changing, nature-challenging, huge-beyond-belief thing. It was bigger than him, and frankly there weren’t many things he considered bigger than him. Most people are the center of their own universe, and it’s rare you get a chance to participate in something that you know is bigger than you and your country. He saw this as a big deal.

The Grand Coulee Dam was indeed a big deal, and continues to be an integral element of life in the Pacific Northwest by producing an enormous amount of electricity for the region and helping to irrigate more than 600,000 acres of farmland. However, it is also today recognized as part of a troubled legacy of stopping up America’s wild rivers, much to the detriment of the wildlife and first peoples who have coexisted with the natural streams for millennia. The effect of the Grand Coulee Dam has been particularly acute, as it cut off 1,100 miles of the river’s salmon spawning habitat. As environmentalists have pressed for the removal of dams in the Pacific Northwest, business organizations—which the communist-sympathizing Guthrie actively loathed, once refusing to play music for the Spokane chamber of commerce—have invoked Guthrie’s music to defend the dams, no doubt recognizing that the region’s large industrial farms and heavy industry rely on the power and irrigation. “One verse of Guthrie’s song talks about the electricity generated by the dams as ‘turning our darkness to dawn,’ ” Don Brunell, president of the Association of Washington Business, wrote in an op-ed in 2012. “Some activists want to remove the dams—but consider what our lives would be like without them.” Meanwhile, some environmentalists have written off Guthrie’s music as “no-brainer” “industrial river ditties.”

But both these assessments miss the true spirit of Guthrie’s Columbia River songs—no doubt in part because the vision that Guthrie bought into when he signed on with the BPA never fully came to pass.

By acreage and cubic yards of concrete alone, Grand Coulee Dam and the irrigation project represented the New Deal at its most ambitious. But those physical feats of engineering paled in comparison to the social engineering the federal government hoped to achieve in the Columbia River Basin’s newly irrigated farmland. As originally envisioned, farms irrigated and electrified by the Grand Coulee Dam would be organized around townsites placed by federal planners and limited to 80 acres to prevent the benefits from going to large landowners.

The journalist Richard Lowitt coined a term for Roosevelt’s Pacific Northwest: The “planned promised land,” a 20th-century synthesis of Biblical deliverance and careful civil engineering, where farmers could relocate, work for themselves, and never again worry about the weather’s whims. For Woody Guthrie, this represented the most concrete solution yet put forth by the government to help the masses of Dust Bowl refugees still feeling the ravages of the Great Depression.

While in Southern California, Guthrie had visited and was impressed by the federal work camps set up for migrant farm workers, which were also celebrated in The Grapes of Wrath. Similarly, Guthrie in his Columbia River songs makes clear his hope that the farms watered and electrified by the Grand Coulee Dam would go to help his Oklahoma kinsmen, who were wandering the country looking for a new place to settle.

In perhaps the collection’s strongest song, “Pastures of Plenty,” Guthrie conveys the deep bitterness felt by the migrant masses toward the country they thought had abandoned them as the economy fell into tatters. “Out of your Dust Bowl and westward we rolled,” he sang. “And your deserts were hot and your mountains were cold.”

The version of the song recorded for the BPA was a minor-key adaptation of the traditional standard “Pretty Polly,” which, Alan Lomax later wrote, has a “starkly brooding melody” that “endows ‘Pastures of Plenty’ with somber melancholy.” Yet the final stanzas are hopeful for the promised benefits of the Grand Coulee: “The lights for the city, for factory, and mill/Green pastures of plenty from dry barren hills.”

Arguably, no government report, study, or memo ever captured the intent of the Columbia Basin Project better than “Pastures of Plenty.”

Yet ultimately it wasn’t to be. Within a year of Guthrie’s employment with the BPA, the bombing of Pearl Harbor thrust the United States into WWII. The Grand Coulee Dam played a major role in the war effort. The electricity it produced was vital to the production of aluminum, allowing Boeing to ramp up its bomber production in Seattle. It also, secretly, began supplying electricity to Hanford Engineer Works for the manufacture of enriched plutonium.

That the dam went to the war effort probably didn’t bother Guthrie much. War was on the horizon even as Guthrie visited the region, and some anti-Hitler rhetoric entered a few of his Columbia River songs. He liked to say his guitar killed fascists, but he must have recognized that a B-17 Flying Fortress would get the job done just as well.

But the war ended up dooming the New Deal vision for the Columbia Basin. It drew millions of Americans to urban industrial centers for work, and following the allies’ victory, the country enjoyed a postwar economic boom unprecedented in human history. By the 1950s, the prospect of grubbing out a living on a small farm in rural America was unattractive to most Americans now enjoying a decent living in the cities. Attempts to draw farmers to the region failed, and the federal government slowly began to loosen its regulations on the size of the farms that used Columbia River irrigation. Today, the water in large part goes to massive industrial farms that bear little resemblance to what the New Dealers had in mind.

As historian Paul Pitzer put it, the so-called planned promised land was a “19th-century plan for a 20th-century economy.”

And yet Guthrie’s Columbia River songs endure to this day as some of the most popular folk tunes in the American canon. It’s easy to understand why. Regardless of their history, there is a hard-bitten optimism in Woody Guthrie’s Columbia River songs that remains inspiring. Taken together, the songs present a powerful thesis: The American worker, given the opportunity, has the power to turn deserts into orchards and rivers into a force strong enough to defeat Nazi Germany. These songs are a refutation to anyone who suggests that the government doesn’t have any business helping the common man.

And while the mass relocation of Dust Bowl farmers to the Columbia Basin never came to be, the ideals of public power that were celebrated at the Metropolitan Theatre have hardly waned.

Throughout the Northwest, public utility districts and municipal power systems like Seattle City Light continue to supply millions of homes with electricity. Many towns today hang highway signs telling travelers that they are “Another Public Power Community,” and the region as a whole boasts more publicly owned utilities than any other in the nation. The area has also enjoyed over the past 75 years some of the cheapest power rates in the country, just as Roosevelt had all but promised it would when promoting the dam projects.

That’s just as Woody would have wanted it. As he put it in one of his tunes, “’Lectric lights is mighty fine,/If you’re hooked on to the power line.” E