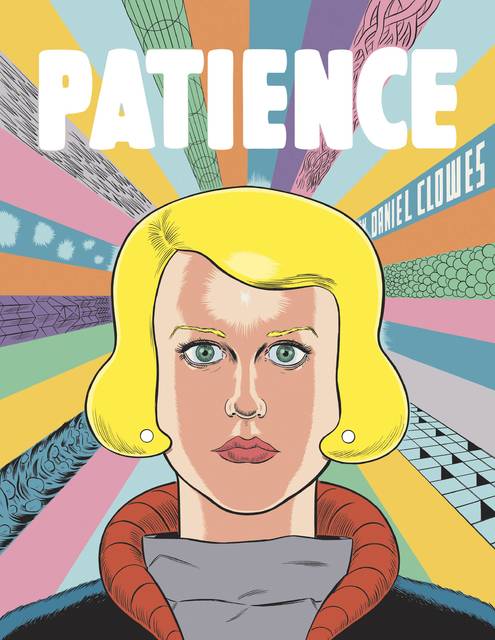

Daniel Clowes says that his new 180-page book, Patience, is the most “comic-like” comic he has ever done.

It’s an interesting comment coming from Clowes, given that nearly everything written about him credits his work as a historical turning point for the comics medium in general. His classic 1997 Ghost World—still Seattle comics publisher Fantagraphics’ best-selling title ever—was one of the first comics marketed as serious “literature” to a mainstream audience in conventional bookstores—a watershed in the now-widely-enjoyed world of “graphic novels” in the West. His oeuvre gets the kind of treatment most artists don’t receive until they’re dead: he’s got a monograph (The Art of Daniel Clowes: Modern Cartoonist), a “critical edition” of Ghost World featuring 12 accompanying essays by authors and scholars, and retrospective gallery shows.

Having to revisit pages and pages of his old work for these commemorative projects—including last year’s 25th anniversary collection of his classic early-career series Eightball—inadvertently plunged the artist, 54, deep into his past. Coincidentally, Patience, his longest graphic novel, is about time travel. “It felt like I was in the world of 1991–2000 while also living in 2010, 2012, 2015, so it very much felt like I was in the world of the story,” Clowes laughs. He says his vibrant science-fiction thriller, five years in the making, is in part his most “comic-like” book because it’s also his most maximalist.

“I think in past work I’ve tried to pare things down to the barest minimum,” he says.“In this one I freed myself up to give as much space to things as I wanted. I tried really hard to make all the rhythms and imagery work very specifically as a comic in the way only a comic can.”

Wiedling comics’ unique power to tell stories via space and sequencing, the book bursts with brilliantly timed “Oh, snap” moments. You turn a page and boom, an enormous spread punches you in the face with a completely unexpected development. Patience is one of the first works Clowes created considering each two-page spread as a single unit, and that sense of scale, combined with the gorgeous full-color treatment, immerses you in its weird world immediately.

The book begins in the year 2012 as Jack, a self-loathing loser, finds out his beloved girlfriend Patience is pregnant. Moved by his deep love for her and the prospect of being a father, he decides to turn his life around and finally deal with his emotional (and financial) hang-ups. When he returns home to tell Patience about his personal revelation, he finds her dead on the floor. As the police investigate him for murder, Jack conducts his own unsuccessful investigation searching for the mysterious killer.

Flash forward to 2029 (rendered in a refreshingly non-apocalyptic fashion—part Jetsons and part Fifth Element): Jack, now a husk of a man, is still wandering around looking for answers when he stumbles upon a blubbering, pizza-loving, jumpsuit-wearing weirdo named Bernie. Bernie happens to have invented a time machine. And thus begins Jack’s insane, decade-spanning cosmic adventure, on which he gets in a number of fistfights and nearly kills a baby with a ray gun in 1985.

Even though time travel is the device that moves the story forward, Clowes purposefully did not research any theories of relativity or quantum mechanics during the writing. “The concerns of making things work out scientifically aren’t at all matched up with what I’m interested in doing in the comics,” Clowes says. “I’m interested in putting these characters in these dreamlike situations and having them deal with that in as realistically and grounded a way as I can.”

Almost never removing his sunglasses, Jack wanders through much of the book as a sort of grizzled, self-destructive vagabond—think Liam Neeson in Taken but with way less action-hero prowess and way more cursing. Despite his best attempts to alter the course of history using logic and planning, he succumbs to his punch-first instincts far oftener than he should, painting himself into a slew of theoretical time-continuum corners in the process. “I’m so goddamn sick of all the science-fiction mind-fuck bullshit,” he thinks halfway through the story.

Despite that disregard for rigorous science-fiction mechanics, Clowes spent six months perfecting the plot line and making sure the myriad of possibilities time travel presents didn’t poke a hole in the story. “Working with all the timelines was really tricky,” he says. “Even as I was drawing the very last page, I was still convinced that the first person who read it was going to say ‘But hey, why didn’t he just do this?’ ”

Not miring the time-travel convention in physics allowed Clowes to put his own interesting metaphysical spin on it. Some of the book’s more stunning two-page spreads are the ones depicting Jack slipping through time—rendered in trippy geometric crystal-structures, goopy organic blobs, and infinite celestial fibers. During these episodes, Jack utters Terence McKenna-like realizations about universal consciousness and “hyper-vivid macro-vision of the secret workings of the universe.”

“In many ways I was trying to write my own religion,” Clowes says. “If I had to imagine what the fabric of the universe was like, what you would see behind the curtains of reality, this was it.”

Although the psychedelic spiritualism is subtle, combined with Jack’s palpable, intense love for Patience throughout the story, the book is one of Clowes’ least nihilistic works yet. There’s some serious heart and sneaking optimism here. It’s a refreshing turn for Clowes, whose sarcasm and self-effacing style came to define Gen-X ennui. Even after his success with Ghost World, Clowes frequently shrugged off his reputation as a “respected cartoonist,” something he regarded as a strange, paradoxical title, and his characters often embodied that malaise. But now, Patience seems to reflect a new Clowes: happily married, a father, and revered as a living master of his craft—as all these recent commemorative projects have reminded him. Instead of scrapping through the void, he suddenly has a lot to fight for. And—despite the huge chip on his shoulder—so does Jack.

“[The story] is based on the sense of how much I know I’d be shattered if something happened to break up my family,” Clowes says. “I can certainly relate to that part.”

Kelton Sears is Culture Editor for Seattle Weekly. He can be reached at ksears@seattleweekly.com. Follow him on Twitter. Get more from your favorite writers with our weekly newsletters.