EDDIE GALE

Eddie Gale’s Ghetto Music

(1968, Water)

Black Rhythm Happening

(1969, Water)

Eddie Gale played for Sun Ra in the early ’60s, and following up on the notices he got for his work on Cecil Taylor’s Unit Structures, he cut these two albums for Blue Note; he’s still working, but there’s not much else in his discography. Ghetto Music and Black Rhythm Happening are so specific to their era that they’re startling today—1968–69 was a time, after all, when black jazz musicians were still tied to a ghetto that was surging with black pride if not necessarily black power. The German label Trikont’s pair of Black & Proud comps (2002) give a taste of the times from the pop end of the spectrum; on the other end, free jazzers like Albert Ayler (Music Is the Healing Force of the Universe) and Archie Shepp (Attica Blues, The Cry of My People) fortified their attack with gospel singers. Gale, too, rounded up a choir, but he made it much more central to the music, which was driven forward by rolling rhythms (Ghetto Music) and funk chants (Happening), while his trumpet, bright and frisky as a bebop-addled mariachi, carries the day. The first album is a tour de force: the sort of grand gestures that AACM might have had in mind when they coined the term “Great Black Music—Ancient to the Future.” The second is funkier but runs into some strange ether when the lyrics start channeling Sun Ra.

EARL SCRUGGS

The Essential Earl Scruggs

(1946–84, Columbia/Legacy)

When Mike Seeger cut his encyclopedic Southern Banjo Sounds, he started in the 19th century and closed with an example of “Scruggs-style.” Bill Monroe is credited with inventing bluegrass, but his mandolin and whine were only half of the formula. The other half came from Lester Flatt’s finely picked guitar and Earl Scruggs’ driving banjo. Monroe’s Blue Grass Boys split in 1948, with Monroe going higher and lonesomer while Flatt & Scruggs played harder and faster. The first disc starts off with three Monroe songs and then follows Flatt & Scruggs up to 1957, focusing sharply on Scruggs, who turned 80 this January, and it’s all you really need to know about bluegrass banjo. The second disc is dicier, with Flatt vanishing after the overexposed “Ballad of Jed Clampett,” replaced with Scruggs’ progeny and random guests. The best, no surprise, is Johnny Cash, who starts off with a story.

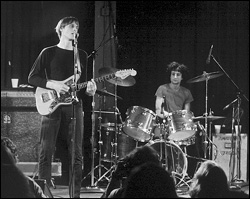

TELEVISION

Marquee Moon

(1977, Elektra/Rhino)

Adventure

(1978, Elektra/Rhino)

Live at the Old Waldorf

(1978, Rhino Handmade)

By the mid-’70s, rock’s newfound intelligentsia was worried. The golden age of hard-rock expansion had decayed to dull heavy metal. The golden age of black pop had fractured into rote funk, disco, and crossover pabulum. The industry was awash with lame “me decade” singer-songwriters. Gram Parsons gave way to the Eagles. The very notion that good and popular correlate in any way had become suspect. Critics scoured the land for any sign of salvation, and in New York many embraced a cluster of new bands working at a Bowery dive named CBGB. The major CBGB bands (Television, Blondie, Talking Heads) were as differentiated as the major pop-art painters of the ’50s; what they had in common (aside from time, locale, and audience) was how they aestheticized the idea of pop. Television was the first of the CBGB bands to get notices, and after two albums adored by critics and ignored by everyone else, it was the first to fold. People tend to pigeonhole Television as a harbinger of the punk and new wave just around the corner, but they don’t sound like anything that came later. If anything, with their grand gestures they recall classic rock: Tom Verlaine and Richard Lloyd were worthy successors to the twin-guitar attack of Eric Clapton and Duane Allman on Layla, but darker and more demotic, which was pretty much where progress seemed to be heading. Marquee Moon was their debut and masterpiece. Adventure was their swan song, softer and more songwriterly, in retrospect a stepping stone to Verlaine’s solo career. The bonus tracks are more of the same, except for “Little Johnny Jewel”—an early, Velvets-influenced single that might have pointed them in a different direction. Live at the Old Waldorf is a welcome complement to the two studio albums: a newly released 1978 San Francisco concert, spanning both albums plus “Little Johnny Jewel,” revving up the guitars and encoring with “Satisfaction.” Too bad it’s being sold as sucker-priced

collectorama.