If life-negating political structures are the result of the suppression of imagination, utopias are visions as pushback. At the University of Washington’s Jacob Lawrence Gallery (The Jake), three new curators, Nadia Ahmed, Sarah Faulk, and Anqi Peng, with support from former director Scott Lawrimore and project assistant Justen Waterhouse, have organized an exhibition series on the conceptions and present-day stakes of utopia. On the 100th anniversary of Jacob Lawrence’s birth, Utopia Neighborhood Club contextualizes utopia within his life. Faulk states, “My hope for the relationship between utopia and the institution this show is happening within is that it can foster a community that encourages imagining radical futures.”

Utopia is literally nowhere; the word comes from the Greek roots not and place. Often an ideal against which we compare current reality, utopias imagine societal overhauls into structures where the subjects’ lives are easier. They are fantastical, such as an island nation where queer women live free from men (but with giant kangaroos) in William Moulton’s Themyscira, or an alternate reality in which native populations in the Congo had learned about steam technology before Belgium’s colonization, as imagined in Seattle author Nisi Shawl’s Everfair. Utopia as a political premise asks us to imagine something radically outside what we know, like universal basic income and prison abolition, and from there sets direction for programmatic goals. Utopias are multifarious, simultaneous, and even contradictory. When Thomas More wrote Utopia almost exactly 500 years ago, reducing the workday to nine hours was one of his farfetched visions.

“Shelter-wear prototypes.” Tad Hirsch and Mae Boettcher. Photo Courtesy of Jacob Lawrence Gallery.

“Utopias are completely relative,” Ahmed tells me. “Everyone envisions something different for a ‘perfect’ world.” The exhibition series and public programs demonstrate this expansiveness of perspectives. The first iteration of the series exhibited Tad Hirsch and Mae Boettcher’s “shelter-wear prototypes” for homeless people, a versatile poncho formed from Tyvek construction material, which suggested the role of the artist in an idealized society as that of social interventionist. In contrast, Zhi Lin’s quotidian drawings of a kitchen and bedroom during China’s Cultural Revolution demonstrated the artist’s preferred embrace of “art for art’s sake, to stay away from the intervention of the communist government.”

How might Jacob Lawrence’s life inform our understanding of utopia? With a large exhibition at Seattle Art Museum, his profound impact on this city is experiencing a surge of recognition. Lawrence is celebrated for his depictions of 20th-century black Southern life, specifically for his documentation of the Great Migration, the relocation of more than six million black Americans from the South to the industrial North between the late 1910s and the 1970s. As Ladi’Sasha Jones writes in Temporary Art Review, “If we can understand the Great Migration at the turn of the 20th century as a radical spatial imaginary, through this lens, the Black city can be framed as an active collective imagining of utopia.” During that era, the many arms of racism were still being flexed via brazen laws such as restrictive housing covenants. In response, Jones writes, “Organized networks sprang up all across expanding Black urban enclaves and became a part of the fabric of Black survival and ascension in the city.”

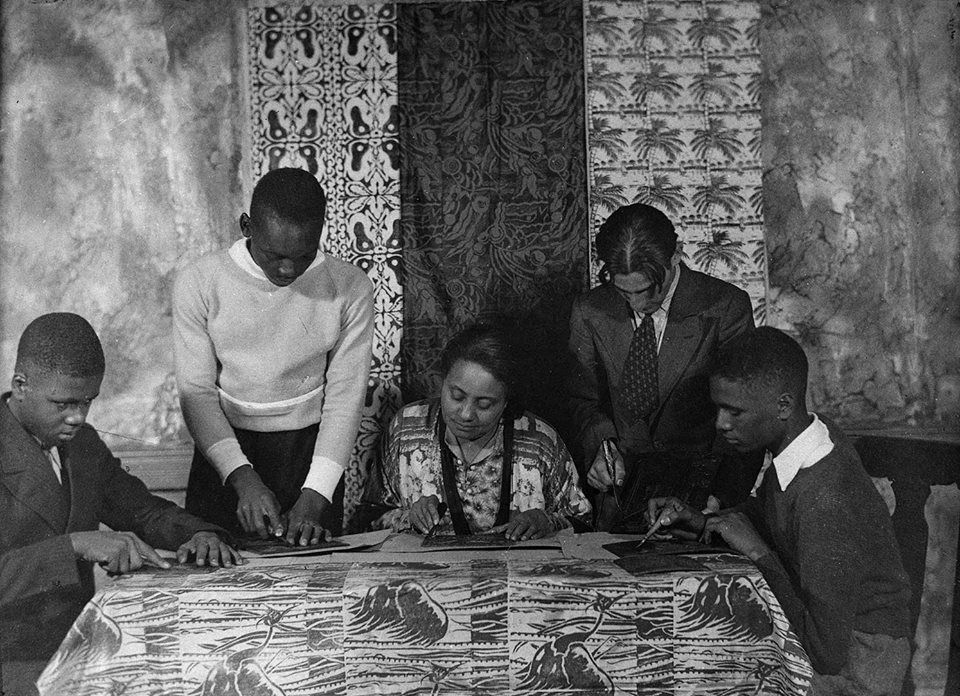

It was at Utopia House in Harlem, a community center started by three black women, that young Lawrence took painting classes. Building a utopia involves rearranging social codes to either change laws or sidestep them, and this art club, where Lawrence laid the foundation for his training, was one example of the many outerworlds within the country built for and by black people.

Jacob Lawrence (second from left), Harlem, 1933-34. Photograph by Kenneth F. Space. National Archives, Harmon Foundation, College Park, Maryland

In early 2016, Lawrimore brought in as the Jake Legacy Artist-in-Residence artist Steffani Jemison, whose work is inspired by Utopia House; her show Promise Machine, Jones writes, “utilizes utopia as a discourse of abstraction within Lawrence’s work and a century of imagining the Black city.” Jemison drew the connection between Lawrence’s work and the utopian impulse in collective migration and community network-building: within her project, Jemison created reading groups around books such as Black Utopia: Negro Communal Experiments in America by William Pease, Black Empire by George Schuyler, and Light Ahead for the Negro by Edward A. Johnson.

On the Utopia Neighborhood Club website, a quote from cultural critic Stephen Duncombe reads “Utopia is No-Place, and therefore it is left up to all of us to find it.” It is clear that the curators placed emphasis on “all of us.” Public programs pack the exhibition series’ calendar, such as multiple forums on the meanings of “neighborhood” and “club”; “How to Organize a Public Library” with Professor Michael Swaine; and a workshop on “DIY Venue Harm Reduction” with architect and curator S. Surface. The exhibition series ends with works by Lawrence, including The Legend of John Brown, a “22-part serigraph series depicting the life and contribution of the important abolitionist,” and features a gallery talk by Royal Alley-Barnes, former executive director of Langston Hughes Performing Arts Institute and Jacob Lawrence’s first graduate student.

“Utopia Neighborhood Club” Opening reception. Courtesy Jacob Lawrence Gallery

Utopianism may seem naive as we question the viability of creating societies separate from the ones we’ve already clumped together with the bulky shrapnel of history. In recent decades techno-utopianists have dominated the discourse with their zealous belief that technology could bring forth a just society, promising that we can invent our way out of our social problems and that new-media technologies and the Internet contain portals to non-hierarchal cybersocieties. As we’ve seen this pipe dream rust and corrode, its spirit persists in political partnerships, product marketing, and even art exhibitions that promise disruption of the status quo through invention-solutions.

Nadia Ahmed states her hope that many students outside of the art program will join the conversation: “People do not take enough advantage of the Gallery, which is why we wanted to ask what people want from it. What could The Jake become to make itself a more accessible space?” This receptiveness to input, instead of a patronizing assertion of solutions, is the first step toward collective accountability.

I’m struck by the relationship between the utopian no-place and no-place as a geographic negation, a term for an absence of a national identity by law or faith. There are those with no place in America: the fugitive, the refugee, the immigrant; for these, no-place is the purgatory state of inhabiting a country that has denied your legal stake in it. Utopian thinking carries varying weight depending on whether you believed you ever had a country to lose. When no inhabitable places are in sight, devising new social orders is less an indulgent fantasy exercise than a means of survival.

In America 2017, these ideas are highly relevant. How will Jacob Lawrence Gallery continue to account for the utopian tradition of Lawrence’s life after this exhibition is over? How can the rich trajectory of utopian thought extend our capacities for imagining and acting beyond what we have known to be possible?

“It’s useful for me to think of a utopian mindset as one committed to hope, creating new possibilities, and new landscapes,” Sarah Faulk says, “but with the knowledge an end is probably never going to be in sight. The work never ends.” A Student Response Part II – The Jake Legacy Residency and The Legend of John Brown + Other Works, Jacob Lawrence Gallery, 1915 N.E. Chelan Lane, jacoblawrencegallery.hotglue.me. Through Sat., March 4. Gallery Talk with Royal Alley-Barnes, 10 – 11 a.m. Wed., Feb. 15.