On July 11, 2008, the price of oil rose to $147 per barrel, a record high. Gas stations engaged in hot pursuit as the price of a gallon rocketed past $4. All hell was about to break loose.

The country’s largest banks had already begun to implode through arrogance and ineptitude. Now the oil market had moved in with a thundering uppercut. Airlines and trucking firms watched their costs punch through the roof. So did every other business great and small, since 90 percent of American goods are shipped in some form or another.

“That was the breaking point of the economy,” says Tyson Slocum, director of the energy program at Public Citizen, a Washington, D.C., government watchdog group. “That’s when businesses said they could no longer fuel their trucks, and that fuel costs were overwhelming their payroll.” So began a surge of layoffs that would push well into the next year.

America’s political leaders could only muster a simpleton’s response. Demand had outstripped supply, they claimed. And it was all the fault of radical environmentalists. If they’d only let us drill for more riches offshore—or on protected lands in Alaska—we could all go back to cranking Toby Keith in our Chevy Tahoes.

It was a fabulous, made-for-TV narrative. Who can forget Sarah Palin shaking her fist at the Republican convention that September, exhorting the legions to “Drill, baby, drill!” What began as a rallying cry soon became an article of faith at cafes and kitchen tables, executive suites and editorial meetings.

There was just one tiny problem: Absolutely none of it was true.

In four short years, the price of oil had risen nearly 400 percent. For this to be a natural occurrence, it would have required a sudden, massive increase in world oil consumption, coupled with equally massive shortages in production. None of which had happened.

“I asked the senior official at Goldman [Sachs] at the time. There were no supply-and-demand issues that could remotely explain the doubling and doubling again of oil prices,” says Dennis Kelleher, a former international securities lawyer. “In order to justify that, it would literally take the discovery of China on the demand side, or the loss of Saudi Arabia on the supply end.”

And those politicians who were bleating about environmentalists? What they conveniently forgot to mention was that millions of acres had already been approved for drilling in the U.S., but remained untouched. The demand just wasn’t there.

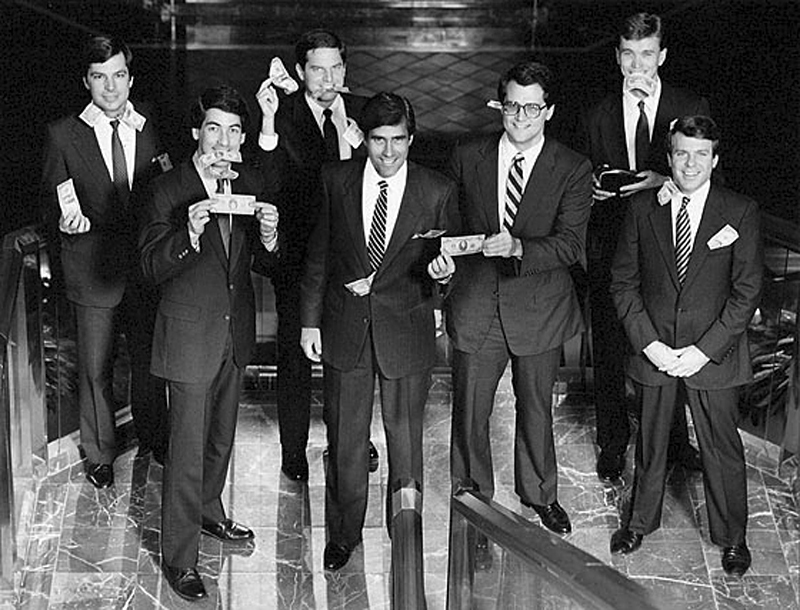

The boys on Wall Street must have had a hearty laugh over this. After all, they knew oil prices had ceased to have anything to do with supply and demand. Eight years earlier, they’d been granted the right to make huge, unregulated bets in the oil markets. Now they’d driven gasoline to the brink, just as they had with the mortgage industry.

The funniest part: All those finger-pointing politicians were their accomplices. This was an inside job.

It happened on the night of December 15, 2000. The country was in tumult over the Bush-Gore election. This diversion offered Republican Senator Phil Gramm of Texas an exquisite opportunity to push American financial stability back 100 years.

That evening, Gramm inserted a 262-page amendment into the Commodities Futures Modernization Act. Leaked e-mails would later reveal that it had been written by lobbyists for Enron, Goldman Sachs, and the Koch brothers, Kansas billionaires who would later fund the Tea Party movement.

Gramm had turned his office into a subsidiary of Wall Street. From 1997 to 2002, the securities and banking industries had lathered him with $640,000 in campaign contributions. His biggest sugar daddies weren’t from Texas; they were Credit Suisse, Morgan Stanley, Bank of America, and Goldman. And he was more than willing to step-and-fetch-it on their behalf.

Big oil, big banks, and big speculators like the Kochs wanted to make monster bets in the futures markets. But they wanted to do it in secrecy—without any government regulation.

The futures markets are where the world trades its raw materials, from wheat to oil, coffee to cattle. They were designed not as toys for banks or speculators, but for merchants who actually use those products. Before a farmer plants his oats in the spring, he can agree to sell them to Kellogg’s at a set price come fall, just as Southwest Airlines can lock in a price now for a delivery of fuel in January. This allows companies to set their costs and income long-term, so their businesses—and their customers—aren’t regularly blown up by wild price swings. Everyone has a stake in keeping prices stable.

Which is why futures had been heavily regulated since the 1930s, when Wall Street last incinerated the U.S. economy. Until then, speculators had regularly terrorized the country by artificially driving up prices and hoarding things like grain.

But the stock-market crash of 1929 offered Congress a teachable moment. The men of Wall Street could not be trusted. It wasn’t just their eagerness to screw their fellow countrymen. Their occasional bouts of breathtaking incompetence made them dangerous to themselves as well. So rigorous laws were enacted to protect both the nation and the banks that ran it.

The futures market would be policed for the next 70 years—until that night in 2000, when Phil Gramm handed the keys to Enron, Goldman, and the Kochs. The amendment passed without hearings or public notice. Democrats, practicing their patented brand of acquiescence, were happy to ride shotgun. President Bill Clinton signed it into law.

Congress members were “bipartisan, effete snobs who thought they knew better than everybody,” says Mark Cooper. He’s the director of research for the Consumer Federation of America, among the many who warned Washington that it was playing with matches near dynamite. He’d soon be proven spectacularly correct.

Gramm’s amendment became known as the “Enron Loophole,” named for the criminal empire that was then America’s seventh-largest company. Though Enron would soon crumble in a heap of avarice and fraud, Gramm & co. had unleashed the parasites, allowing them to prey on American commerce.

Prior to the change, speculators were generally kept to no more than 30 percent of any given market. Anything beyond that became dangerous. That’s because they have no concern for the things they’re buying or the people who use them. They’re simply betting on price swings. The more volatile the market, the more money they make. Most sell well before they’ll ever take delivery of, say, a load of sugar.

Yet Congress had set them free. Banks like JP Morgan and Lehman began to rally large, institutional investors to bet on oil. It took them just five years to pervert the market’s very purpose. By 2005, they’d set off a buying frenzy that launched prices into the stratosphere.

Sherri Stone, vice president of the Petroleum Marketers Association of America, likens it to buying a home. Under normal conditions of supply and demand, you might have a few other people bidding for the same house. “But with speculation, now you have 200 other people bidding for that house. You’re going to pay an enormous price for this house.”

By the time the economy began to collapse in the summer of 2008, speculators had cornered a stunning 81 percent of the oil market. Some had even begun to hoard fuel, just as robber barons had done a century before. Olav Refvik, a top trader at Morgan Stanley, became known as the “King of New York Harbor” because he was leasing so much storage space.

Yet the bankers’ incompetence would once again prove dangerous to themselves and everyone else. They’d already sabotaged the housing market. Artificially high fuel prices were the second prong of their attack.

The U.S. economy was officially in free fall.

Think of Wall Street banks as not much different than your neighborhood bookie. After all, there’s little difference between betting on Starbucks stock or a Dodgers game. The smart ones realize they can make a handsome living just sitting back, wisely setting odds, and making a killing off the transaction fees.

But what separates the two is that bankers violate a cardinal rule of the bookmaking trade: They’re degenerate gamblers themselves. And history says they’re very much in need of adult supervision.

In just the past 25 years, the financial industry has gone from the savings-and-loan crisis to the tech-stock bubble to the accounting-fraud scandals to the mortgage-industry collapse. Pepper in a ceaseless string of criminality—from Drexel Burnham Lambert to MF Global—and you realize the industry has routinely set off large bombs in the U.S. economy for a quarter-century.

Worse: The pattern is accelerating.

This reign of depravity just happens to correspond with deregulation, the legacy of Ronald Reagan. Surely he was right to reduce the red tape and paperwork garroting small business, the nation’s largest and most stable employer. But his disciples took it as a one-size-fits-all theory. The people benefiting most were those who could afford to buy senators like Phil Gramm.

Deregulation of the futures markets would solely serve America’s greatest welfare queens, Big Oil and Big Finance. Over the years both had purchased competitive advantages from Congress, making a mockery of the free market. America’s five largest oil companies receive $20 billion in welfare annually, largely through tax breaks afforded to no other industry. Big Financiers pay half the personal tax rates of their brethren at community banks. Even after buying off the umpires, they still couldn’t stand on their own two feet.

“Nine of the largest financial institutions in the world failed” in 2008, says William Black, a former bank regulator-turned-economist at the University of Missouri-Kansas City. “That should petrify people. All of them pulled the pin on their own grenades.”

When the economy collapsed, speculators found themselves with a small problem: No one could afford to buy gas. In just a few short months, the price plunged from $147 to $30 a barrel.

Some good came from this. President Barack Obama would soon follow Sarah Palin’s charge, increasing drilling in the U.S. He also strong-armed Detroit into producing more fuel- efficient cars as part of their bailout.

Finally, the simple fact that we’re still broke four years later has caused U.S. consumption to steadily decline. Today, America exports more oil than it imports for the first time since the 1940s.

Yet the heirs to Phil Gramm have done their best to protect speculators, hosing the nation in the process. “Every time the economy starts to show signs of rising, the oil speculators jump in,” says Joseph Kennedy II, a former congressman from Massachusetts. “They suck the life out of the economy.”

As analysts spoke of recovery in April 2011, the price of gasoline approached the $4 mark. The wicked swings had resumed. Last spring, it topped out once more at $3.96 a gallon.

But this time it had become difficult to screech about environmentalists or supply and demand with a straight face. Even the banks were confessing their sins. An analyst for Goldman Sachs admitted that banks like his had added an artificial 40 percent to the price of a barrel. Everyone from the Federal Reserve to the CEO of ExxonMobil has conceded much the same.

That led Bart Chilton to do a little math. He’s a commissioner with the Commodity Futures Trading Commission, which is supposed to oversee oil trading. By his calculations, the owner of a Honda Civic is sending $7.30 to JP Morgan and men like the Kochs every time she fills her tank. For an F-150 pickup owner, the banker fee is $14.56 a tank.

Chilton believes the annual cost to the trucking industry is a whopping $29.1 billion. For airlines: $9.8 billion. That means every time you fly, every time you buy an apple or a beer, the nation’s thirstiest welfare queens take a cut.

Stone, of the Petroleum Marketers Association, which represents 8,000 convenience stores and oil wholesalers, says your neighborhood gas station doesn’t get a piece of anything. Typically, a gas station makes just seven cents a gallon, all of which is eaten up by credit-card fees.

Yet it’s the elderly who take the greatest beating. In 1979, Joe Kennedy founded Citizens Energy, a nonprofit that provides heating oil to the poor and aged in 22 states. Three years ago, it cost $1,200 per winter to heat a normal house. Today it’s $4,000, he says. To hear Kennedy tell it, Gramm’s amendment shouldn’t be called the “Enron Loophole.” It should be known as the “Let’s Try to Starve Grandma Act.”

Osama bin Laden could only have dreamed of causing such widespread damage to the U.S. economy. But both parties in Congress remain willing to protect Wall Street at all costs—even if it means terrorizing the country.

“We’re going right back to the robber-baron days,” says Kennedy. “And it’s eating away at our heart and soul.”

The late 1980s were a quaint period, when admirals of finance were still eligible for punishment under criminal law. Savings and loans were collapsing, just as their larger counterparts would 20 years later, pillaged by executive incompetence and fraud.

So federal prosecutors did something that would never happen today: They convicted 1,000 of the biggest and worst offenders. They also filed some 800,000 civil suits, and banned sleazebags from ever working in banking again.

But Washington didn’t grasp the bloodbath’s obvious lesson: Bankers still couldn’t be trusted. Reagan’s “Government Bad, Private Sector Good” mantra had become the nation’s official business plan. Instead of watching the wicked more closely, deregulation allowed Big Finance to rampage untethered.

By the time George W. Bush reached office, the philosophy was so entrenched that, without fanfare or any official change in law, the feds decided that Wall Street basically had immunity under fraud statutes.

That was clear by the early 2000s, when accounting fraud became the height of fashion in executive suites across the land. The feds would prosecute the most egregious chieftains at WorldCom, Tyco, and Adelphia. But some of the country’s biggest names were caught rigging their books as well, firms like Merck, Halliburton, and AOL. All were allowed to walk. The game had become fully rigged.

Economist Black, author of The Best Way to Rob a Bank is to Own One, says there are one million law enforcement officers in America today. Only 1,300 are devoted to white-collar crime. Most police departments don’t have a single detective working the country-club set. When Enron imploded under the largest fraud in Texas history, the Houston PD was busy rousting check-bouncers.

With local investigations rare and the feds purposefully averting their gaze, bankers were allowed to take down the housing market in a scheme 70 times the magnitude of the savings-and-loan collapse.

“Wall Street is a high-crime area in which we basically have no cops on the beat,” says former securities lawyer Dennis Kelleher, head of Better Markets, a nonprofit devoted to protecting taxpayers from the too-big-to-fail crowd.

One might expect this to have occurred under George W., who made no bones that his presidency was all about aiding his fellow trust-fund swells. But it would only get worse under the self-styled change agent, Barack Obama.

The appointment of Attorney General Eric Holder said it all. He’d been a partner at the law firm of Covington & Burling, whose clients included Goldman, JP Morgan, Citigroup, and Bank of America. The year before he joined the Obama administration, he made $2.5 million through fees from the very people he was supposed to prosecute.

Even more comical: Lanny Breuer was named head of the Justice Department’s criminal division. He’d previously chaired the white-collar defense unit at Covington. Prosecutions on Wall Street slammed to a halt.

Black estimates that at the height of the mortgage crisis, two million fraudulent loans were being written each year, largely through lenders inflating buyers’ incomes. But not a single major figure was ever prosecuted. Had those 1,000 savings-and-loan criminals from the 1980s practiced their larceny under Bush II or Obama, they would have been given million-dollar bonuses and retired to beach homes in the Hamptons.

It was under these pleasant skies that oil speculators launched their attack on America. In 2008, when their assault became evident, even some Republicans called for investigations. But that quickly ended when Obama became president. Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell, not one for subtlety, announced that his party’s Mission One was sabotaging Obama.

Democrats managed to pass the Dodd-Frank Act in 2010. One of its goals was to hand the oil market back to actual users and allow the feds to crack down on excess speculation. Kennedy believes this alone would have reduced the price of gas by $1 a gallon. But after Congress announced its great triumph over Wall Street, it quietly teamed with bankers to gut the law. The Commodity Futures Trading Commission, which was supposed to spearhead the crackdown, saw its budget slashed. Speculators filed suit, essentially arguing that they had the inalienable right to violate the country.

The financial industry would eventually spend $100 million to stave off regulation, buying congressmen, setting up fake public-interest groups, and funding academics to produce laughable studies. Two years after Dodd-Frank passed, the feds have yet to touch a single hair on a speculator’s head.

The propaganda campaign has worked. “What they’ve really won is the intellectual struggle,” says Black. “People can’t conceive of a world without these massive institutions, and can’t believe they’re a negative influence.”

Take the Tea Party movement. Its followers are largely concentrated in the red states, statistically the nation’s poorest and thus most easily damaged by high gas prices. Yet their greatest benefactors, the Koch brothers, have boasted of being among the top five speculators in the world. So while Tea Partiers rally against regulation and government interference, the Kochs steal $14 from them every time they fill up their Fords.

“This is all part of the same formula of lower taxes and less regulation,” says Kennedy. “That formula wins elections and ruins the country.”

As gas prices neared $4 this spring, Republicans reprised their Great Campaign of Idiocy from 2008. Once again environmentalists and liberals were to blame, this time for blocking construction of the Keystone Pipeline, a massive project that would allow the shipping of oil from Canada to Texas.

Presidential aspirants Newt Gingrich and Michele Bachmann claimed they’d lower gas prices to $2 if elected, presumably by magic. Congressman Paul Ryan of Wisconsin, considered the party’s brightest financial mind, proposed cutting the Commodity Futures Trading Commission’s staff by two-thirds, just in case they might decide to grab coffee in the general vicinity of Wall Street. Mitch McConnell said he’d be happy to address speculation—but only if Democrats agreed to allow drilling on environmentally sensitive lands.

“They believe nothing was wrong with the markets in 2008,” says Cooper of the Consumer Federation.

Obama, meanwhile, was doing an inverse impression of Teddy Roosevelt: Instead of walking softly and carrying a big stick, he brayed noisily and brandished a twig.

When gas prices approached $4 in April 2011, the president announced the creation of the Oil and Gas Price Fraud Working Group. This was Obama’s grand plan to finally strike a blow against our enemies within. But while the announcement came with fireworks, these new crimefighters would meet just a few times over the next year. Malevolence uncovered: zero.

“Anybody who looks at the non-activity of that working group knows that the only fraud was in naming it,” says Kelleher. “I think their non-record speaks for itself.”

Some senators like Sherrod Brown of Ohio and Bernie Sanders of Vermont have pushed earnestly for the feds to step in. But Republicans say they’ll block any move against Wall Street—with swing-state Democrats there to serve the appetizers.

“There’s a free-market philosophy that continues to exist,” says Mark Williams, a former Federal Reserve examiner now at Boston University. “If you’re a trader, you should have the right to trade. But if the greater community is harmed, you shouldn’t have that right. We still live in a democracy, right?”

Michael Greenberger, a law professor at the University of Maryland and a former director at the Commodity Futures Trading Commission, is among the few who believe a reprieve is in store. He believes Wall Street’s relentless ineptitude may finally do it in. Two months ago, JP Morgan was the latest to set itself aflame. One of its traders managed to gamble away $2 billion in just a few weeks. The damage is expected to reach $7 billion or more by the time the cinders go out. “The JP Morgan episode really struck at the nerve of the American psyche about banks and what kind of damage they can do,” says Greenberger. “These people who are doing nothing productive for the economy are walking away and, even in failure, collecting millions and millions of dollars.”

Then again, the same people have been doing the same thing for 25 years. Yet regulation just keeps getting weaker. “You will know that somebody’s serious when they put 500 FBI agents and a dozen of our best prosecutors on Wall Street,” says Kelleher.

In the meantime, it could all get a lot worse if Mitt Romney is elected. Even after the JP Morgan fiasco, he reiterated his plan to repeal Dodd-Frank, which also contains measures guarding against future bank bailouts.

Writes Politico: “Romney’s reaction is the equivalent of putting out a small fire in your house, then deciding that the lesson is you need to stuff your house with matches, throw out your fire extinguisher, and cancel your fire insurance. And doing all this after the house nearly burned to the ground less than four years ago.”

These days, the oil market has again begun to dive—through no help from our leaders. A stalled Chinese economy plus fears of serial bank crashes in Europe have caused speculators to scatter. Prevailing theory: The world may soon be too broke to buy gas.

But at some point, the economy will show signs of recovery. And Washington has ensured that the speculators will return, there to suffocate it in its infancy.