As I was growing up in New York state—where the residents want you to know they don’t live in “The City”—the Revolutionary War, Civil War, Woodstock, and the music of The Band were all entangled in the region’s mythology; on occasion, the boundary between the distant and recent past blurred completely. The Redcoats moved through our town during the Revolutionary War, 109 of our residents served in the Civil War, The Band’s music—made a familiar 100 miles away—was a ubiquitous presence, and Woodstock took place on a farm down the road from a house our family used as a hunting cabin. In my young mind, Ulysses S. Grant and Robert E. Lee, Levon Helm and Max Yasgur all seemed to be of the same era, one far removed from my own.

Life as a child is surreal anyway, but my hometown of Pound Ridge was like re-enactment bootcamp, with the adults hell-bent on making little anachronisms of us all. Fife-and-drum corps was a rite of passage for most, and Memorial Day, Labor Day, and Fourth of July events all ended with gunfire at the village cemetery set on a beautiful hillside in the middle of town: “Burial Hill,” they appropriately named it, where the graves seemed like museum installations. As kids, it seemed unfathomable to think that you could be set on that hillside for eternity, lying beside strangers who had died in ways that we couldn’t comprehend.

Most of the homes in the area were hundreds of years old, and came with incredible stories. But more important, they came with ghosts. Even the newer houses seemed haunted, and we kids were sure they were built on Native American burial grounds. My first meaningful kiss was on the “pound” that Pound Ridge was named for—the flat, long hill where the Native Americans kept their game animals. Roads ran through these ridges: “Pound Ridge Road,” “High Ridge,” “Long Ridge.” These ridges, with their dark winding roads, held secrets, waged bets, mercilessly took lives on blind curves, and provided boundless beauty and depth of field. If you listened, there was the sense that they were willing to reveal their secrets.

Our fifth-grade teacher, Ms. Levine—a Liz Taylor look-alike in her 40s, with a bit of Gloria Steinem thrown in—taught science, was tough as nails, and was so unlike the other teachers who had long ago morphed into that strange state prevalent among grade-school teachers in the 1970s, where they began to take on characteristics resembling birds of prey, with their strange bodies and elongated beaks taking precedence over their more-human traits. I was smitten with her—we all were. We were a bit scared, too.

Every time we were about to take off for a school holiday, Ms. Levine brought out a guitar and we would sing songs. The one I always remember singing is “The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down,” from The Band’s self-titled record in 1969. I had no idea the song was recorded after I was born—it could have been from the Civil War. It felt timeless, yet far away from the post–Brady Bunch era that I was weaned in. When we sang it, it was as if it and we had always existed, and things were as they had always been. We sang it at day camp, too, along with “This Land Is Your Land” and “On Top of Old Smokey,” of course. I remember those brown-bag lunches of soggy PB&J sandwiches and warm Mott’s Apple Juice, and the counselors, aged 14 or 15, with their long hair parted in the middle and hip-huggers. “Virgil Caine is my name,” they’d sing out, almost certainly after smoking pot in the woods.

Though they’d been with me in a sense since grade school, in my teens The Band was one of the first groups I fell in love with. As budding teenagers, each of us has such a strange mixture of ingredients that need to be activated. For me, The Band was one of the vehicles that helped me connect with what was churning inside me. I needed something that connected me to nature and allowed more space for my imagination to fill—allowing my own vision to percolate within its confines. It had to look and feel a certain way, have a metaphysical structure I’ll never understand to this day, to speak to my soul. It was the beginning of a journey away from alienation—one still unfolding today.

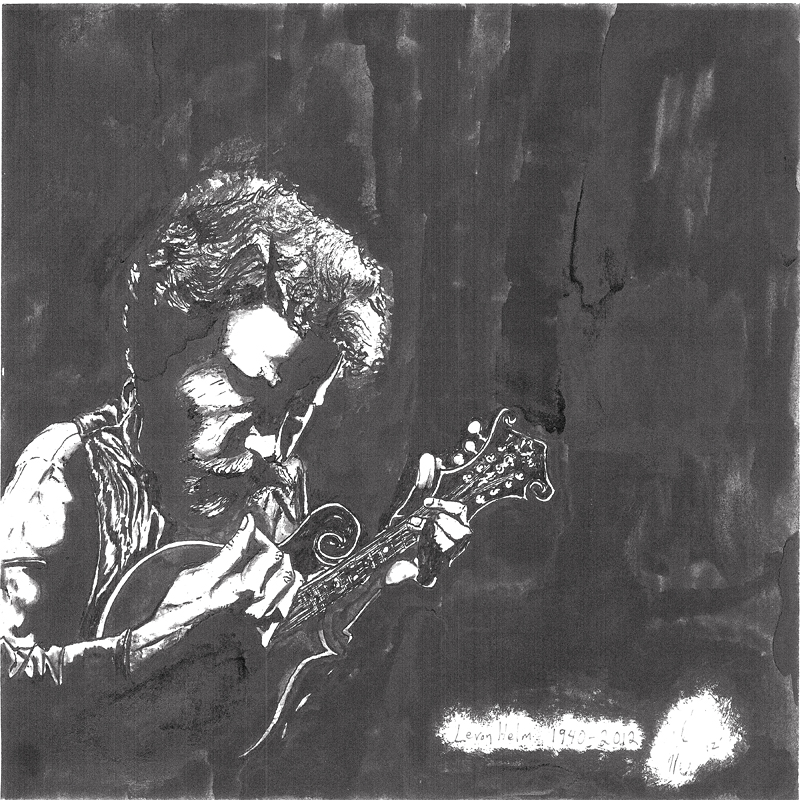

The Band’s voices—in particular that of Levon Helm, the drummer, and often lead singer, who died on April 19, and was the voice behind “The Weight,” “Up on Cripple Creek,” and “The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down,” among many others—had a familiarity and a depth of spirit that made me feel safe during a time when darkness seemed to be baiting me around every narrow passageway, cutting through the Northeastern woods.

We all know there is no way to fight what we need. Just like falling in love with a human, we fall in love with our music. As a teenager, the process can be intense, even painful. It happens in one of those riptide moments, when all chemicals converge—those that hover in the ether and those that ignite internal sparks, making that precise moment ripe for burgeoning hormones and primeval yearnings to come forth.

It’s in that pinnacle moment that music becomes something that isn’t just a void-filler that could make you feel good, distracted, even joyful—this time it presents itself as a vehicle that could take you down through the depths of spirit and soul, make you aware you have a soul. It’s the beginning of a true love affair that cannot happen until we gain enough footage under our belt so that the ability to reflect takes on a life of its own; music becomes not just the present and future, but for the first time the past, too. And it becomes personal.

I didn’t need to know Levon Helm to feel like I knew his soul, his spirit. Maybe that’s what I loved about The Band, why to this day I still need their music in my life. It’s as if they were characters from a time beyond, yet the sorrow in their voices is eternally poignant.

As a kid, I didn’t know who was singing which of The Band’s songs or who had written which—it didn’t matter. They seemed like they were all haunted by the same ghost, a ghost I was familiar with.

My family had a little house in Bethel, New York, a town in the Catskills, right down the road from Yasgur’s farm where the Woodstock festival was held. It had once belonged to a great aunt who left it to my grandma when she passed away. By the time I was born, it was mostly used as a hunting shelter, not suitable for living. Its decrepit state may have had something to do with the fact that my grandmother’s sister had committed suicide in that house via gas oven. My grandma always told us kids “She died of a broken heart,” and for many years I believed a broken heart to be no different than a heart attack or cancer. It was something that could happen to any of us.

I remember the shot-out windows, the half moon on the outhouse door, the metal porch chairs, and the complete silence. The house stood in a meadow surrounded by 150 acres of deep woods. I was too young to remember, but my dad always liked to tell the story of how Max Yasgur supposedly held me in his arms when I was a baby. As a teenager, my dad would take me to the field where Woodstock all went down, and I recall feeling an intense ache in my chest and throat, a sweet kind of sadness. I had not been there, yet I felt I had.

Until recently, I never thought much of the fact that I carried a copy of The Band’s debut, Music From Big Pink, in my purse to the studio for the making of each of our records. During playbacks I’d stare at the pictures in the booklet for inspiration, sort of like carrying a rabbit’s foot—something to anchor me to my earliest emotional connections. There’s something about that famous black-and-white photo of The Band, looking like young Civil War soldiers, standing before the mountains of West Saugerties, New York—taken just a couple of counties away from my childhood home—that brings me great comfort.

I still have dreams where I am slipping back into the quiet pastoral beauty of that region, where I get to revisit the mountains, those ridges, the woods, and those narrow roads lined with stone walls. In these dreams I never know if I’m leaving for the first time or coming home for the last. They are always unsettling that way.

I have friends lying on Burial Hill now, people who died much too young. It brings me a peculiar pleasure knowing it’s not just strangers buried there anymore. Now my story is as embedded within those ridges as the ones told to me as a kid. I don’t know if I’ll ever make it back there, but when I see that hillside cemetery in my head, it’s Levon Helm’s voice I hear.