If modern gay history started at Stonewall, the 1981 identification of HIV/AIDS began its postmodern chapter. Thirty years later, when safe(r) sex and drug cocktails have at least contained that menace (with a vaccine possibly on the horizon), it may be hard for kids born in the ’80s and ’90s to understand the panic and confusion that crushed the ’70s spirit of a gay (or pansexual) utopia from Greenwich Village to the Castro. Most of the programming at this year’s Seattle Lesbian & Gay Film Festival is celebratory and affirmative, in keeping with the times. (Musicals! Dancing! Comedy! Boy cheerleaders!) Gay marriage is on the march. And, apart from certain Republican primary battlegrounds, tolerance seems to be rising in states both red and blue.

But we have to look back, as two strong new documentaries at SLGFF explicitly do. One comes from the east, the other from the west. One profiles a famous film scholar and activist who succumbed to AIDS, the other features ordinary folks on the front lines, now middle-aged, who somehow survived. In both, there’s the poignant contrast between snapshots of young, healthy men in the ’70s—who wore their mustaches proudly and their cut-off shorts tight, as God intended—and video testimonials from decades later, when lined faces and gray hair hint at all the funerals and hospices behind them.

A guy who studied silent movies—and all cinema—for hidden queer clues, Vito Russo spent nearly a decade touring his clip-and-lecture show The Celluloid Closet just like the road shows of pre-nickelodeon-era cinema. What he discerned, especially during the pre-code era, was “a secret language” of male glances and hysterical outbursts, of intense female friendships that seemed to exclude leading men. But such characters—think of Robert Walker in Strangers on a Train—were usually bound for the standard “cure or kill” resolution.

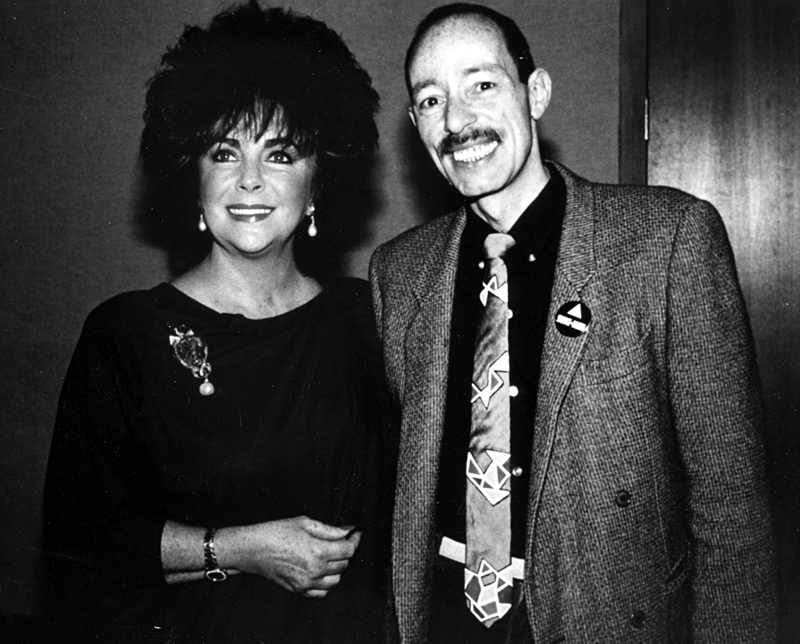

Russo finally published The Celluloid Closet in 1981, and it’s now in the canon of cinema studies. Bound for HBO next year, Vito (Cinerama, 6:30 p.m. Sun., Oct. 23) pulls back the dust jacket on Russo, who vowed at 18 to leave New Jersey for Manhattan and never go back. Never during his mid-’60s youth was he uncertain about his sexual identity or rejection of Catholic notions of sin. “I never bought any of it,” says Russo (1946–1990). “I knew they were full of shit.” (His Italian-American family, contrary to the usual clichés, accepted him as he was.)

After moving across the Hudson, Russo remembers tartly, part of the indignity of being gay pre-Stonewall meant suffering regularly raided bars that served watered-down cocktails, because patrons had nowhere else to drink. After Stonewall, Russo was busy as an independent film scholar, TV host, and journalist who profiled his friends Bette Midler and Lily Tomlin for The Advocate. Then came the ’80s, the AIDS crisis, and a return to activism, which consumed the last decade of his life.

Likewise during that decade, the Bay Area was initially slow to recognize the “gay cancer” that, one subject recalls in We Were Here, was greeted with a kind of DIY epidemiology. He remembers reading a flyer in a drugstore window, illustrated with Polaroids of the poster’s Kaposi’s sarcoma lesions, warning his fellow gay men about this unnamed new malady. A nurse—the five interview subjects are identified only by first name—tells how AIDS wards and clinical trials were developed ad hoc, as the medical community struggled to understand and treat the fast-spreading virus. A counselor remembers how he was a failure at anonymous sex—here he hilariously demonstrates his best come-hither look—but a success as a hospice worker, providing intimate support and friendship to the afflicted.

If Vito is about the man, We Were Here is about the many, the community in microcosm and not its individual heroes. (Harvey Milk is only briefly glimpsed in old TV footage and headlines.) By reducing the AIDS epidemic to a few speakers, and distilling those speakers to near-anonymous voices, the doc both personalizes and generalizes the catastrophe. Speaking with no small share of survivors’ guilt, the five get to represent the roughly 15,000 who died before effective drug treatments were introduced in the late ’90s. It’s a terrible responsibility, eloquently served. (The film screens at the Egyptian, 5 p.m. Sat., Oct. 15.)

We Were Here ends on a sad but settled note. Certainly things are better today than they were 30 years ago when, as Russo bitterly notes in Vito about Reagan-era indifference to the AIDS crisis, “The right people are not dying. It’s only fags and junkies, and no one gives a shit.”