Two years after being hired as the assistant program director at 107.7 The End, Marco Collins was holding down the evening shift at the most important alternative rock station in the city when an ecstatic friend called from L.A. to tell Collins about an obscure 12-inch single he’d just picked up.

The track was a bizarre hodgepodge of acoustic slide guitar and sloppy beats with slurred rhymes dropped on top. The artist was a 22-year-old coffeehouse denizen.

“I was like, yeah, this is amazing,” Collins says. “But we only had it on vinyl.”

Collins started spinning the record at night, when his audience was more adventurous and his bosses were more flexible with what they allowed him to play. Collins took an intensely personal interest in the music he wanted to add to the station’s rotation, and his excitable demeanor led to fights with the station’s program director, Rick Lambert—until the two realized their creative tension made for an ideal match.

“We’d debate every artist,” Lambert says. “Every week we’d have debates. That’s what a program director and music director [the post to which Collins had ascended by this time] do.”

But this single wasn’t a tough sell, even thought it was released on a tiny label (Bong Load Custom), had virtually no representation, and had zero buzz and no hype. Within a month, it became the station’s most requested song, and Collins was wearing out the vinyl. He converted the song to tape, and Lambert gave the go-ahead to add the song to the entire day’s rotation.

The song exploded, and phones rang off the hook. One call was from Geffen/DGC Records. They were interested in signing the artist, and wondered whether Collins thought he’d be a good fit for their roster.

The year was 1993, the artist was Beck, and the single was “Loser.” From obscurity, Collins had plucked what would become one of the biggest songs and artists in alternative-rock history. Collins played “Loser” not because he’d been pitched the song by a label or because it had climbed the charts and into his realm of consciousness, but because when he heard it, he heard a hit.

“[Marco] heard hit songs regardless of the genre of the music,” says Debi Lipetz, who has promoted music to radio stations in the Northwest for CBS/Epic/Sony since the ’70s. “Marco could find a well-written song hidden on the last track of an album. He would find the great songs.”

Collins was the first person to play Weezer’s “Undone (The Sweater Song)”; he leaked both Pearl Jam’s Vitalogy and Vs.; and once took a call from Kurt Cobain and Courtney Love, pleading with him to explain to his listeners that the leaked copy of In Utero he was spinning included some out-of-date mixes. Today, the songs Collins and his colleagues brought to the public in the ’90s remain the backbone of alternative rock radio. Early next year, when Cleveland’s Rock and Roll Hall of Fame unveils its updated interactive DJ exhibit, Collins will be included as the DJ representing Seattle’s musical explosion of that decade. He joins KJR’s legendary Pat O’Day as our city’s only representatives in an exhibit on historic and influential rock DJs.

Listen to an audio reel of Collins’ Rock and Roll Hall of Fame clips.

“Marco was an essential part of the scene,” says R&RHOF curator Howard Kramer. “At the time that the Seattle scene exploded, radio was still very important. It was still the main way you heard music.”

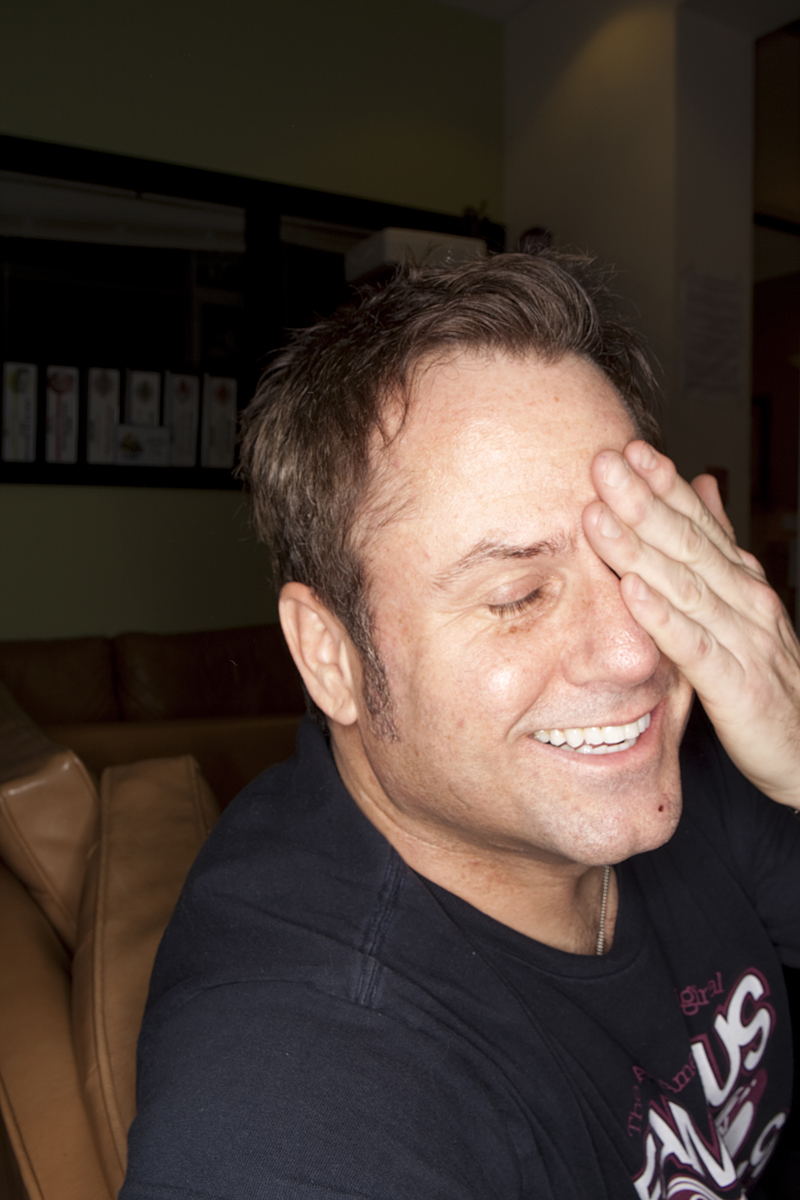

His time at The End now canonized, Collins’ 12 years away from the station since leaving in 1998 have been considerably more tumultuous. On the morning of this past September 27, Collins’ journey brought him to a fill-in shift at KEXP, where he was spinning, only partially in jest, as the “homeless DJ.”

“I’m not entirely homeless,” Collins told his listeners, “I’m kind of just in between places.” Unemployed, subbing at KEXP, and programming a couple of online stations for Slacker.com, Collins was being evicted from a home for recovering addicts, moving in with a friend. After earning an income in the neighborhood of six figures for much of the past 10 years, Collins is broke.

“Everything I made in the last decade,” Collins says, “I spent on coke.”

Now 45, Collins has the energy of a 17-year-old. Standing behind the mixing board at KEXP, he never stops moving, rarely quits talking, and shuffles among the mounds of CDs he’s pulled to his side: Beck’s Sea Change, Patti Smith’s Horses, and MGMT’s Congratulations. His assistant, Kevin Staiger, says Collins keeps the music cranked higher than the station’s other jocks. He dances more too.

On a Saturday night, Collins is filling in for Michele Myers, fielding texts from friends congratulating him on the Senate’s vote repealing the military’s antigay “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” policy. He’s sent Staiger off to find some Village People in the archives, to no avail. Collins hasn’t spoken publicly about his homosexuality since Out did a story about gay members of the grunge scene in 1994.

Collins never made his sexuality an issue on the air, partly because he didn’t want to affect ratings, but also because he didn’t see it as relevant. There was also the fear of the unknown: Even in liberal Seattle, being gay in the early ’90s wasn’t anywhere near as socially acceptable as it is today.

“I mean, it amazes me we’re having a legitimate conversation about gay marriage now, because in ’91, even in 2001, it was like ‘No way, not happening, we shouldn’t even talk about it because it will piss people off,’ ” says Dave Meinert, a longtime friend who employs Collins part-time at Fuzed Music, where Collins helps promote Seattle bands like Fences.

Before Collins came in for his KEXP shift, he had some fun with Staiger, a volunteer who’s a physics and math major at the University of Washington. Collins told Staiger that since a photographer would be stopping in during the show, he’d better wear a suit. Staiger took Collins at his word, and showed up in a shirt, tie, and slacks. Meanwhile, Collins came in wearing a silver shark-tooth necklace and a Famous Franks of Brooklyn T-shirt, looking every bit the aging frat boy—an impression he’s dealt with his entire life, even though he never spent a day in the Greek system.

“Kevin, I’m hungry, dude, but I’m also broke as fuck,” Collins says to Staiger, their banter more like that of college roommates than mentor and student. “But I have soup here. Are you up for soup?”

Staiger retreates to the KEXP kitchen and heats up a box of Trader Joe’s organic tomato soup. When he returns, he serves Collins dinner in a ceramic Cupcake Royale coffee mug.

Collins’ humble situation is the by-product of having partied away his past largesse and failing to hold down a full-time job. But for the moment, his free-agent status has allowed him to focus on his personal life.

“This year was supposed to be all about working on sobriety,” Collins says. “For nine months, in the sober house, I stayed sober. Then one day I drank some wine. This has been one of the biggest challenges of my life. The way I look at this is you may never be 100 percent perfect, but I’m working on it and trying to grow on a constant basis. But it has been a challenge.”

When Collins was at The End, kids would ask him for autographs. When he returned to town in 2008, he felt as if he’d been forgotten. But John Richards, KEXP’s premier DJ and associate program director, remembered him well. Richards, who was working at a Wallingford restaurant the first time he heard Collins spin “Loser,” credits him for being one of two DJs—the other being longtime KEXP and club disc jockey Riz Rollins, who spins several times a week on the station—who’ve had the greatest influence on his career.

When Collins moved back to Seattle to work for Meinert, he reached out to Richards, as well as to friends still at The End. Collins and The End have discussed possibilities, but KEXP proved a better immediate fit. It was the station he was listening to every day, and he’d grown tired of being the retro guy.

Aware of Collins’ personal struggles, Richards nonetheless agreed to start giving him fill-in shifts, slots typically reserved for people who have worked their way up the KEXP ladder as volunteers.

“In his case, you have one of the most well-known Seattle DJs in history, in my opinion,” Richards said. “I said, ‘Hey, man, I would love to have you on the air.’ I think I’m loud and swear a lot, [but] that guy is out of his mind. I love to see someone more animated than I am about music.”

Beyond his personal demons, another issue at hand was how KEXP’s proudly independent-minded audience would react to a commercial DJ like Collins coming into the mix, especially one associated with a rival local station. Richards says the audience reaction since Collins’ 2009 debut has been at least 90 percent positive. Spinning a track that veers a little too close to his old stomping grounds can get him in trouble with a few grumpy listeners. Yet some of those songs are ones Richards plays with impunity.

“I play ‘Cannonball’ by the Breeders, and I get people going, ‘F-you, you commercial dick,'” Collins says with a snicker. “But John can play that song a million times and people are like, ‘Yeah!’ They’re totally fine with it. It’s a perspective thing.”

In Collins’ heyday, The End gave him a long leash, because the songs he added to the station’s rotation were getting picked up by a growing flock of alternative stations around the country.

“This was pre-Internet; smart record companies were watching [the radio stations],” says Susie Tennant, who at the time was the Geffen/DGC promotions rep in the Northwest, and now runs PR and marketing for Town Hall. “If you had smart and aggressive programmers, you pay attention. It’s like having A&R people all over.”

Programming risks, like playing a song by a total unknown with no fan base, endeared listeners to Collins. “Why not look at what you do on the radio as being an A&R source?” Collins theorizes. “The payoff will come back tenfold. You make Beck a huge fucking artist, he’s gonna come do shit for you. He’s gonna talk about you in interviews. The vibe will come back around.”

Weezer thanked Collins by including an on-air interview with Collins and a shout-out to him on this year’s Pinkerton reissue. Geffen and Beck expressed their gratitude in 1994 by playing a pair of End-sponsored shows in town a few months before the March release of his Geffen debut, Mellow Gold. The first show was a 21-and-over set at the Crocodile. Collins’ recollection is that Beck’s DAT machine—on which his beats were recorded—had broken, so he played acoustic and got booed.

The next day, Collins took Beck out for lunch. Beck was bummed. He knew the show hadn’t gone well. And that night he had an all-ages show at the OK Hotel, famous as the venue where Nirvana had debuted “Smells Like Teen Spirit.”

A couple songs into the set, Chris Ballew, who would soon front the Presidents of the United States of America, observed Beck floundering. As he started laying into “Loser,” dragging the opening notes up and down the neck of his guitar, something came over Ballew, who jumped onstage, grabbed a microphone, and started beat-boxing the rhythm of the song.

“I got chills because of the vibe, just the crowd screaming, freaking out,” Collins says. “It was like night and day from the 21-and-up crowd.”

A few days later, Beck invited Ballew to travel with him to Olympia and work as an instrumentalist on his album in progress, One Foot in the Grave, and then to join his touring band to promote Mellow Gold.

“And that was the beginning of my professional career as a guy getting paid to make music,” says Ballew.

Collins grew up outside Nevada City, Calif., a hippie community near Lake Tahoe. There, in the early ’80s, Collins listened to a free-form radio station called KVMR that featured a punk-rock show from midnight to 6 a.m. on Saturday mornings, hosted by a disgruntled female DJ with the handle “Cindy Snyde.” Collins and his high-school friends used to tape each show and trade them throughout the week.

For a kid in a small mountain town, the show was Collins’ introduction to the world of punk, from Agent Orange and the Germs to the Dead Kennedys and the Clash.

“I remember hearing ‘Police on My Back’ for the first time and going, ‘That guitar is fucking genius!’ ” Collins says. “And the greatest thing about it is she would set it up with perspective. So she’d go on the air and be like, ‘Yeah, I was walking to work today and, you know, because I have dyed pink hair and, you know, I’m wearing a trench coat, the cops have to stop and mess with me. And that’s always the case. You walk through the town, the cops are always gonna screw with you. So this is for you.’ And it was the best thing ever, dude, when you’re a kid and are like ‘Fuck you! Fuck the man!’ “

When he was 16, Collins sat in with a KVMR DJ, helping out by fetching records and doing other scut work. Around the same time, his dad, a cop, divorced his mom and moved to Nevada City. Collins was sad for his mom, in whose custody he remained, but was secretly excited for himself.

“My dad just always wanted me to be the jock. I wasn’t that guy,” Collins says. “I tried every fucking sport in the world for him [and] hated them all, except swimming. And of course I go to a high school where there’s no pool. Once I sort of said ‘Fuck you’ to him and started doing what I wanted to do, everything changed in my life.”

He studied telecommunications at San Diego State University, and while still in school started working at San Diego’s 91X, where he created the station’s first-ever local-music show—and was the first person to put Eddie Vedder’s voice on the radio when he spun his band, Bad Radio. When the station’s parent company, Noble Broadcast Group, decided to spin off a sister station in Seattle, they tapped Collins.

Collins arrived in Seattle the week KMGI 107.7 changed its call letters to KNDD and rebranded itself as The End on Friday, August 23, 1991. When Collins hit town, the first two records he was handed were Pearl Jam’s Ten and Nirvana’s Nevermind. He’d always been a fan of Nirvana, but—despite his earlier advocacy of Bad Radio—didn’t warm right away to Pearl Jam. “I did have to be talked into it,” he says. “As I had to be talked into Candlebox.”

Ten was released the following Tuesday. Nevermind was released the next month, on Sept. 24, followed closely by Soundgarden’s Badmotorfinger on Oct. 8. Collins, at 26, was being dropped into a tight-knit music scene that was blowing up.

“When bands learned that I was gay—especially Nirvana—all of a sudden I became a part of [the scene],” he recalls. “It was almost like I became a little bit of a misfit to them.”

A turning point for Collins came when he was scheduled to introduce the Supersuckers at Mercer Arena. Collins ran late, and the band’s annoyed frontman, Eddie Spaghetti, walked onstage and announced into the mike: “I’m Marco Collins, and I’m a big fag.”

Collins arrived backstage just after it happened, and when the Supersuckers finished their set, the guys in Mudhoney gave Spaghetti hell. Spaghetti was shocked: He had no idea Collins was actually gay. “I’m a jackass from Arizona. It didn’t really mean ‘I’m a gay person and I’m hiding in the closet.’ It just meant ‘I’m a jerk,’ ” Spaghetti explains. “We were kind of excited to have Marco come up—’Someone from the radio station is going to come up and introduce the band, how cool is that?’ My shoes are size 10, and I can’t believe I fit that whole thing in my mouth.”

Collins was mortified. He thought he’d just been outed in front of thousands of listeners. But the only real reaction he got was from a kid who called in and said, “Dude, I didn’t know you sang for the Supersuckers.”

“I viewed my audience as not being as open-minded as I think I gave them credit for,” Collins says. “Now I think about it too, and I think, ‘There were a lot of kids that looked up to you when you were on the air. Maybe you could have been that sort of role model that you never had.’ When I grew up, there were no gay people that were role models at all. I can remember watching a gay-pride parade on TV with my parents, and all I saw on TV was dykes on bikes and dudes wearing nun costumes. And it freaked me the hell out when I was a kid. I thought, ‘Oh, no, I couldn’t be gay.’ Even though I knew inside that I was.”

Things started to unravel for Collins when The End let Lambert go in 1997. The station had just been purchased by Entercom in the wake of the Telecommunications Act, which is roundly blamed for the massive consolidation of radio in the years since. Collins told his new superiors he wanted to quit, but they convinced him to accept a compromise: They’d relieve him of his music-director duties and continue paying him the same salary to keep doing his show at night.

With his annual take-home in the six-digit range for working only four hours a night, Collins had a lot of time and money on his hands. He maintained a nice loft on Capitol Hill and was prone to last-minute trips to Europe. It marked the beginning of a decade in which Collins slipped into a pattern of partying, going to rehab, diving back into his job, and heading right back to the party. “I was living like a rock star,” Collins says. “It was a lot of fun, but that’s sort of when the drug habit got a little crazy. It did get out of control in New York.”

Collins keeps the specifics of his debauchery to himself, because when he talks about his years spent struggling with addiction, he’s not speaking in the past tense. He doesn’t want to jinx himself or be unrealistic about his situation. “If I was so far out of the woods with this—if I had, like, five [or] 10 years under my belt with sobriety—I’d be like, ‘Oh, yes, and then there was the time, you know . . . ‘ “

Collins left The End in 1998 to start a record label with Rage Against the Machine’s management. After a crazy year at an office sharing space with Wu-Tang Clan—during which he had to hide demo CDs from Old Dirty Bastard, for fear he would steal and pawn them—Collins left to become music director at VH1 in New York, at a time when the network was trying to make the transition from Michael Bolton to Pearl Jam. To Collins—used to discussing with one program director which new records to toss into the airplay rotation—VH1 was a whole different monster. Music meetings became a cacophony of a dozen Viacom employees, all pushing music from labels who’d treated them to glamorous junkets and perks. On one occasion, Collins got chewed out by his boss for introducing a single that they hadn’t discussed at an earlier strategy session. That record—”Higher,” by Creed—went to #1, and a year later Collins’ boss apologized.

“When I heard it, I was like, ‘It’s a stone-cold hit. This is perfect for the new generation that we’re bringing in to VH1,’ ” Collins says. “But because I didn’t fight that battle in the strategy meeting, I got my ass reamed.”

Collins left VH1 in 2000 after only a year, the same length of time he’d been at his previous gig with Movement Records, the label he helped start with Rage Against the Machine’s management. Maintaining a full-time job over the past 10 years hasn’t always been conducive to Collins’ “lifestyle.”

“I feel sort of like it was a disjointed decade,” Collins says. “I’d start doing some killer project or job, and then I’d spin out and move onto the next job and, you know, have a stint in rehab in between. The last decade, I’m just glad it’s behind me.”

From Andrew Harms’ chair in the booth at KNDD, the assistant program director can see Lake Union, Capitol Hill, and a list of songs about to play on his midday show—to follow “Sick of You,” a new track from Cake, who are booked to play The End’s Deck the Hall Ball, just days away. He’s also blogging, and the topic of the day is the Grammy nominations. End staples Alice in Chains, Pearl Jam, and Soundgarden have all received nods.

In 2011, the songs Collins introduced to his audience, which remain at the heart of The End’s programming—from Nirvana’s “Smells Like Teen Spirit” to Pearl Jam’s “Jeremy”—turn 20, as does the station itself. It’s the same age that albums from the likes of Led Zeppelin were when they were played on classic-rock radio in 1991. In 2011, ’90s alt-rock is now classic rock. But today, Harms says he’s spent more time talking about the nominations of newer artists on The End’s playlist than of the old warhorses. “It’s funny—I’ve found myself mentioning more that Florence and the Machine and Mumford and Sons and Arcade Fire have been nominated than those three [older] bands,” Harms says.

The End and other commercial stations no longer introduce obscure tracks to the public the way Collins once did. That’s a function that has been taken over largely by the Internet, where YouTube videos and mp3s lead to record deals. The End’s role today is to introduce its listenership (according to Arbitron, The End averages four times the market share of KEXP) to songs that have percolated up through the Internet.

“Now radio is not always the first, but they’re the ones who take it from one level to the next,” says promoter Lipetz. “In the old days, if you had a record that was played in the top 10 at any radio station, you were pretty much guaranteed an audience. Now it’s part of the mix.”

Harms points to British buzz band the xx as an example of The End’s continued influence. While the xx were making their way up the online ladder, Harms started playing their single “Crystalised.” The song and the band have since scored a AT&T commercial featuring Olympic speed-skater Apolo Ohno, and the xx played a hugely popular set at the Gorge’s Sasquatch! Festival.

Still, Collins would like to see his former employer take more chances. “I just think in a lot of ways alternative radio has been forced into a really weird place where a song has to be a massive hit for somebody to take a risk,” he says. “It used to be a sort of breeding ground for new bands. If I were to create my perfect radio station, it would be a radio station that didn’t let Pitchfork beat me to a band. I want to be the radio station who’s bringing people a reason to listen to the radio.”

In many ways, that is the role KEXP plays. But even Richards concedes that a show like his—with an influential, national reach online—doesn’t have the same impact that mainstream radio once did. That’s partially because of the new avenues for discovery on the Internet, but also because KEXP plays new or relatively obscure music every day.

“We play so much new music and so many demos and crazy shit,” Richards says, “[that] it takes a while for something to jump out from the other records that we play.”

Seattle’s KJR-FM, like KNDD, was the most influential station in town during its heyday in the 1960s and early ’70s, when it played new music. Its star DJ, Pat O’Day, became an international radio icon. But in the ’80s, KJR shut the door and stuck to bankable hits from that heyday (it’s since gone through multiple format changes). Is it possible, now that grunge and alternative hits have come of age, that The End would consider such a move, shutting out new music and focusing on the songs it’s most closely associated with?

“I hope not,” replies Harms. “I feel like if we got rid of new music, it wouldn’t be The End. I feel like it would die then. I feel like the people who listen to our radio station have the ability to like both on the same station. It’s not like old fogies listening to classic rock. It’s a tough time finding that balance. The station’s at a really good place right now, where we are doing really well with the balance. It hasn’t always been that case. That is the trick. That is the key.”

Today, Collins is in a holding pattern, considering his next move. He’s developed an affinity for independent film in recent years, and volunteers as a front-desk receptionist for the Seattle International Film Festival. He’s also been discussing a film project with Meinert that he prefers to keep hush-hush, and has been focusing on staying sober.

“It has to be cold turkey,” Collins says. “It’s the toughest battle I’ve ever fought in my life, sobriety. If I ever relapse and I fall off the wagon, it’s because I had a bottle of red wine with some amazing meal. That’s always, always been the thing, and then I’m fucked. I am a textbook drug addict.”

Collins says he’d love to land a regular radio gig again. And though permanent slots at KEXP don’t open up very often, Richards says Collins has become “one of the most loved and respected DJs by the fellow DJs,” and that he’d definitely consider Collins for future opportunities. At a minimum, he hopes to get Collins on the air more often.

“He’s got a great background in radio,” Richards says. “He can help us not make mistakes in the future, or help us do the right things. He knows more about radio than most people do—at least what he can remember.”