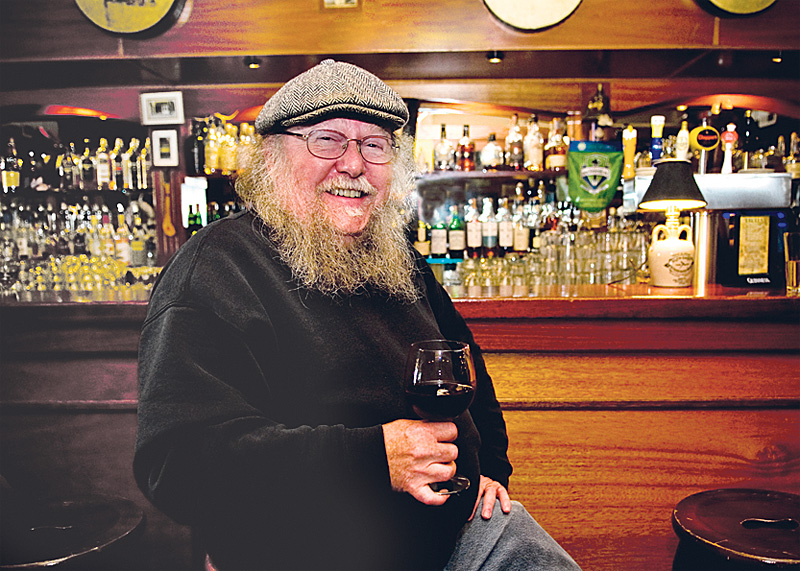

Seattle social worker Joe Martin never knew his father—Dad died shortly after Joe was born to his Irish mom in Boston—but he seems to know everyone else. “Hey, Joe,” says the Pike Place Market Balloon Man passing by. Others nod and wave. He’s been at an aisle table at Kells Pub for just a few minutes, and already an ensemble of his friends, clients, and acquaintances have filed past, none of them stopping to interrupt, of course, seeing as how he’s having a serious moment with a pint of Guinness.

It’s a brief play time for the round man with a tweed cap pulled over his bald pate, a wispy-bearded, 5-foot-tall leprechaun who looks like he fell off a charm bracelet. He will be 60 in September, he says, having spent almost 40 of those years pulling others out of emotional, financial, and alcoholic free falls. He finds housing for the homeless, help for the penniless, teeth for the toothless. Some arrive in such despair at being evicted or losing their meager dole that suicide sounds like a nice way to end the day. But we can fix these things, Martin says, and he does.

After graduating from Northeastern in 1973, he worked as an attendant at a Boston mental hospital, became a teacher in the VISTA program, and eventually found his way to Seattle, working at a mental-health institute. With other activists, he co-founded the Downtown Emergency Service Center and—his base of operations today—the Pike Market Medical Clinic in a vacant tavern site in 1978. Now in a modern facility at Post Alley and Virginia Street, it serves 3,600 patients annually, most of them low-income and elderly.

Four years ago, Operation Nightwatch, a Christian group serving people on the street, named Martin its annual Hero of the Homeless, and a few years earlier he’d been honored as “a compassionate housing activist” by the Low Income Housing Institute, which named one of its Georgetown renovation developments Martin Court. He lives with his wife Martha and teen sons John and Brendan (as in Behan, the Irish writer) on Capitol Hill and buses to work in jeans and a sweatshirt. He doesn’t need much of anything to get by. “If you want to know what God thinks of money,” he says, “just look at who he gives it to.”

Martin recalls demonstrating in the ’70s against the arrival of the gas-guzzling, air-fouling supersonic transport at Boston’s Logan Airport, thinking the country was finally waking up to the threats to its environment. “And today we’re dealing with the biggest oil spill in our history,” he moans. Progress and social change for the underdog has been equally glacial, he says.

Almost two-thirds of the clients who come to the Pike Market Medical Clinic have mental disabilities and addiction problems. About a third are homeless and physically disabled. It’s important to keep in mind not only who they are but who they were, Martin says.

“I talked to a man at the Morrison Hotel [a downtown facility for the homeless] who looked like he stepped out of GQ,” says Martin. “Handsome, well groomed. He said, ‘I don’t belong here. I’m not one of these people.’ He drank himself into poverty.”

“The point is that we all could be one of ‘these people,'” Martin says. “Any of us, for a number of tragic reasons, could end up on the street.” Fortunately, Joe Martin will be waiting should we arrive.