Nine years ago, David Struckman was working the phones when the walls began to shake. It was February 28, 2001, the same day that movement in the Juan de Fuca plate sent a 6.8-magnitude shockwave across Puget Sound.

Inside his home on a nine-acre spread in Issaquah, paid for with earnings hidden from the Internal Revenue Service, Struckman, wavy-haired and perpetually tan, dialed into a morning teleconference with the 15 members of his company’s executive council. Scheduled for later was a second conference call with the small army of independent sales agents who hawked the tax-avoidance audiotape packages that had made him and his business partners rich. All in all, the day was unfolding routinely.

And then the house shuddered. Not because of a shift in the tectonic plates—the quake wouldn’t hit for another few hours. Standing on the front porch was a federal agent with a battering ram. On the other end of the phone, the council listened as agents from the IRS Criminal Investigation division busted through the front door.

About that moment, an estimated 300 IRS investigators across the country went raiding. It was one of the largest coordinated tax-evader crackdowns in the agency’s history. At the heart of it was Global Prosperity International, a benevolent-sounding company that federal officials would later describe as a pyramid scheme evolved for the digital age. Struckman prefers the term multilevel marketing group. But instead of women’s makeup or knives, Global “sold people truth,” he says. Less abstractly, Global sold, through a series of expensive audiotapes and offshore investment retreats, the notion that the Constitution doesn’t empower the federal government to collect income tax.

Following the raids, Global’s founders—Struckman; Daniel Andersen, the company’s 33-year-old chief financial officer from Boston; and Lorenzo “Zo” LaMantia, the jovial multilevel-marketing veteran who planned Global’s offshore investment seminars from his home in Oxnard, Calif.—were all detained while federal investigators searched their homes. All told, the IRS confiscated thousands of company records, hours of videotape, and documents containing the names of the Global “qualified retailers” who had bought into the Global system. Then the investigators left, evidence in tow.

Grand-jury proceedings followed, but the government’s case didn’t progress fast enough to snatch Struckman before he left the country. A criminal indictment was handed down in May, after he’d fled to Panama. In his wake, both LaMantia and Andersen made deals with the U.S. Department of Justice to testify against him.

Two years later, Panamanian police showed up on his doorstep in the mountainous township of David. He was taken into custody, driven by car to Panama City, and eventually returned to the U.S. According to court documents, Panamanian authorities classified it as a deportation. Struckman now says it felt more like a kidnapping.

At his 2007 trial, federal prosecutors said Global had cost the U.S. government untold millions in tax revenue and catered to a potentially dangerous subculture known as the “sovereignty movement,” a group that counts among its onetime members Oklahoma City bomber Terry Nichols.

But in a phone interview from prison earlier this month, Struckman insisted to Seattle Weekly that he’s never been an advocate for the violent overthrow of the government; he just believes in the gospel of personal sovereignty. “I believe that the right to freedom was given to us by God,” he says. “Free enterprise is freedom, and free enterprise means that if you make the money, you can pay taxes if you choose to do so.”

It’s a position that has landed many an antitax promoter in prison. In 2004, a Seattle federal court judge sentenced Keith Anderson, the sovereignty-movement guru whose ideas about the illegitimacy of the U.S. tax system formed the backbone of Global’s chief product, to 20 years in prison. Struckman himself was convicted of conspiracy to defraud the United States.

At his sentencing hearing, he told the court “I’m done fighting the IRS.” Speaking from the low-security Terminal Island federal correctional institution near Los Angeles, Struckman says he’s sticking to that promise—except he’s actually not.

As Struckman tells it, the IRS investigators who conducted the investigation used illegal means to gather evidence that they later attributed to a source whose real identity is still in dispute. So he’s appealed his conviction, even though he’s just about done serving his time.

In August, Struckman will walk out of prison after nearly five years in federal custody. But he’ll be on a short leash. The special conditions of his release seem designed to prevent him from backsliding into his old multilevel-marketing ways. To pay the $2,938,267 in restitution he owes, Struckman will have to find a job that issues him actual pay stubs, not cash. He’s barred from working for himself. Nor can he accept employment from anyone he knew prior to his incarceration without approval from his probation officer. And upon request, he’ll have to disclose all his financial records to the IRS.

But a win on appeal may result in the overturn of his conviction, with the added benefit of vacating his probation agreement. It might also give him room to sue the government for civil-rights violations. Perhaps more important, it would free him from the thing he’s railed against for nearly 30 years: government control.

Who Was “Ted?”

According to search-warrant affidavits, the investigation into Global Prosperity International began not long after the company was founded in 1996. Special agents from the IRS began staking out Struckman’s home in Issaquah. They confiscated his garbage, from which they began to piece together the company’s inner workings. Undercover IRS agents later traveled to Cancún to attend Global’s “wealth-building” seminars. Sometime in 2000, investigators claimed they began receiving phone calls from an anonymous source they dubbed “Ted.”

“Ted” had information. Not just on Struckman’s business dealings and spending habits, but intimate family details: names, phone numbers, bank accounts, the location of the vault where Struckman allegedly kept $40,000 in gold, and the supposed marital problems of his two adult daughters.

At trial, Struckman’s attorney, Robert Bernhoft, pressed government prosecutors to reveal “Ted’s” identity, arguing that much of the government’s evidence was derived from this anonymous source who may have had information favorable to Struckman’s defense as well. Compelled before the trial by U.S. District Court Judge Robert Takasugi, the government finally came clean: “Ted,” they claimed, was Gary Moritz, the current husband of Struckman’s ex-wife Bonita, mother to his daughters.

But at an evidentiary hearing prior to trial, Bonita claimed that couldn’t possibly be true. Bonita testified that in the years since she remarried, Moritz and Struckman had barely interacted. Her daughter, Jennifer, backed up the claim.

Moritz himself couldn’t say whether he was “Ted” or not. Mostly because he couldn’t remember. At some point prior to the 2007 evidentiary hearing, he fell off a ladder while cleaning out his gutters. According to testimony, Moritz suffered a brain injury that robbed him of his long-term memory. Called to testify, he said he couldn’t remember his daughter’s name, much less whether over the past half-decade he’d been feeding investigators information on the activities of his wife’s ex-husband.

“If ‘Ted’ isn’t Gary Moritz, then the information must have come from another source,” says Bernhoft. Judge Takasugi barred any evidence derived from “Ted” from being introduced at trial, stopping just short of calling the government agents who oversaw the Global investigation liars.

Struckman was convicted anyway. But in June 2009, his lawyers got a chance to present his case before three federal appeals court judges in Seattle. Arguing on Struckman’s behalf, attorney Robert Barnes told the three-judge panel that because the true source of the evidence attributed to “Ted” had never been revealed, the government agents who led Struckman’s prosecution had violated the Brady rule, the famous Supreme Court holding that requires federal prosecutors to divulge any evidence that could help prove a defendant’s innocence or impeach the testimony of a government witness. Barnes asked that Struckman’s conviction be overturned.

A year later, the ruling has yet to come down. The judges could order the IRS agents responsible to be disciplined, request a new trial, or go so far as to throw out Struckman’s conviction. If they do any of these things, they’ll be relying on Takasugi’s determination that the government was hiding something—but without knowing exactly what might have been hidden.

“Nobody knows how exculpatory the info could be,” or how it could have aided Struckman at trial, said Barnes at the hearing. But that is the fault of the government, he argued. And for that, he said, they should be “denied the fruits of their illegality, which here was to put Mr. Struckman in prison.”

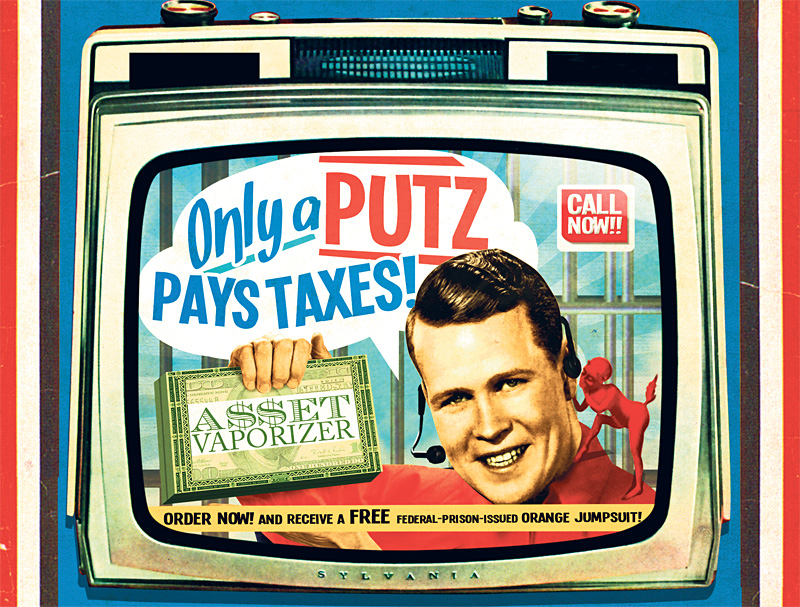

A Game for Rubes

No one likes paying taxes. Most have equal dislike for the federal agency charged with collecting them. Back in 1998, there were so many complaints about the IRS that Congress passed the IRS Reconstruction and Reform Act, legislation designed to make the agency less of a horror to work with. By then, Struckman and his cohorts had already managed tap into that anti-IRS sentiment and spin it into gold.

In a back story he repeated often, Struckman would explain how his feud with the IRS came to be. In our phone interview, he said it started when the agency put a lien on his mobile home and coerced him into a repayment agreement that left his earnings significantly garnished. But missing from his account were a few key details, specifically an explanation as to why the IRS did this.

Struckman was born in Seattle in January 1960 into a blue-collar family of Mormons. After high school, his father told him he needed to learn a trade. So he took a welding course at a Renton vocational school, and eventually got work at Seattle’s Marine Power & Equipment as a journeyman welder. For the better part of the next 20 years, he worked as a welder and fabricator.

He was promoted to foreman sometime around 1988. His added responsibilities included doling out the biweekly checks. Very soon he realized that some men on his crew were taking home paychecks much fatter than his own. Curious, he asked why. He was directed to a meeting. The names of the group and the speaker escape him now, Struckman says, but this is where he was introduced to the tenets of sovereign-citizen philosophy on federal taxation: A certain number of rich families control the country’s finances and are privy to myriad ways of avoiding paying federal taxes; the taxation of citizen income has no basis in actual law; you can opt out of government jurisdiction simply by sending a letter to the appropriate agency giving up your Social Security number.

All of it was pretty out there, he admits. “But I started doing my own research, and the more I dug, the more I began to find people who thought like me, and the more I began to think that what it was they were saying was honest and true,” he says. Afterward, paying full freight in federal taxes seemed like a game for rubes. Struckman says that he began taking out what he estimates to be the maximum in exemptions. This did not go unnoticed by the IRS.

When an IRS agent showed up at his mobile home in Renton, his wife Michelle threatened divorce if he declined the government’s deal to bring him back into compliance, he says. (According to court documents, Struckman refers to at least three women as his ex-wife.) With penalties and late charges, Struckman estimates that his bill to the government totaled around $75,000. After charting out a payment plan, he signed the IRS’s deal. Michelle left him anyway, he says. (She could not be reached for comment.)

Despite the financial and romantic setbacks, Struckman’s belief never faded. “I was raised to question authority if something didn’t make sense,” he says. “And I don’t mind paying taxes if that’s what the law requires. But until they could show me exactly where it was in the law that made paying taxes mandatory and not voluntary, I wasn’t going to give them a dime.”

The Puerto Vallarta Seminar

By 1996, Struckman found a new gig as a “marketing networker.” But multilevel marketing doesn’t allow for quick upward movement. And Struckman wasn’t happy with the amount of money he was making. So he began to search for the ideal organization in which he could launch himself to the top of the pay structure. He landed at Investors International, a firm that Struckman would later use as the blueprint for Global Prosperity International.

Like Global, Investors International sold an audiotape series on how to build wealth by hiding money in offshore bank accounts. They also made money selling tickets to retreats, held outside the U.S., where attendees were sold high-risk investments. At one such seminar, in Puerto Vallarta, Struckman met 28-year-old Daniel Andersen.

Struckman says that he and Andersen, a former carpenter, were respectively the company’s #1 and #2 salesmen. With his linebacker physique and tailored suits, Andersen looked as if he’d been hired from Central Casting to play the overprivileged bully in a John Hughes–style teen romance. But Struckman was impressed.

“Dan had savvy and drive,” says Struckman. Even better, “he was in it for the money.”

Struckman’s portrayal of this period plays out like a Horatio Alger tale, with the two of them bootstrapping their way up to what should have been a higher tax bracket by way of unbridled free enterprise. Along the way, they got a chance to rub elbows with a number of like-minded tax-deniers, like Investors International founder Rudolph Linschoten, perhaps the progenitor of the multilevel-marketing tax-shelter scheme.

“Linschoten didn’t invent the idea of pure trusts, but he was maybe the first to combine it with a multilevel marketing structure,” says Jay Adkisson, who has been tracking offshore tax-shelter promoters on his website Quatloos.com since the advent of the Internet. “And that was the same sort of structure that made Global Prosperity successful.”

Pure trusts are essentially bogus financial entities that exist only on paper, explains Adkisson. Companies like Global and Investors International were paid to help their customers set them up, then transfer ownership of their assets to the trust. The main selling point was that buyers would still maintain control and have access to all their assets, though they technically owned nothing.

To a person who has a significant problem contributing to the U.S. government’s general fund, that kind of tax shelter might sound like a dream. Unfortunately, says Adkisson, the government has long considered the so-called pure trust an obvious and illegal attempt to evade taxation.

Pure trusts have been around forever, says Adkisson, but they didn’t become nearly as popular until scammers discovered the Internet and its mass-marketing powers. From 1993 to 1996, Linschoten took investors for an estimated $6 million. He was arrested in 1999 while conducting an investment seminar on a yacht just outside the Bahamas, and later sentenced to five years in prison.

Three years before Linschoten’s arrest, Struckman and Andersen broke off on their own. They dubbed their new company the International Institute for Global Prosperity. (The name varied over the years.) They brought with them a key group from Investors International, including Keith Anderson. It was Anderson whom Struckman and the other Global principals paid to set up the trusts that they funneled their earnings into. And it was his theories on taxation and sovereignty that formed the backbone of Global’s chief product, the “Gateway to Financial Freedom” audiotape series.

“I Own Nothing”

Like Investors International, Global offered potential investors an opportunity to rise through a tiered system selling the series. Struckman also gave investors the option to jump to the top of the pyramid with a hefty financial investment. Those who bought in at the top level would be made privy to double-secret “income protection” methods available only to—as Global advertised it—the filthy rich.

Struckman began traveling across the country on a Global–themed speaking tour. In small hotel conference rooms, he’d introduce himself, then confidently explain how the federal government is not empowered to collect income tax. That was the main thrust behind Global’s pitch: The owners, Struckman included, were all blue-collar guys who had gotten rich by asserting their sovereignty from the federal government, and you could too.

In a video of those events provided to Seattle Weekly by his lawyers, Struckman told audiences that to succeed with Global, it was necessary to “become a product of the product.” To prove exactly how sovereign he was, he stated that it had been years since a check was actually written in his name. Cash was the medium of exchange in most, if not all, of his financial transactions. He had become, as he put it, “lien-proof, levy-proof, and judgment-proof.”

“I own nothing,” he said.

With Struckman overseeing the marketing side of the businesses, sales boomed. As did membership. In just a few short years, Global went from holding recruitment meetings in cramped living rooms to attracting thousands of eager prospects to bimonthly investment seminars in Aruba, Cancún, and other tropical locales. At some of those conferences, Struckman bragged that Global was attracting nearly 300 new members a week. Before investigators shut it down, Global took in an estimated $40,000,000, say court documents.

Steve Kassel, a former IRS revenue officer in California who tracks financial fraud at etaxes.com, says that tax schemes like Global’s tend to attract a type. “Generally, they’re people who are wired to distrust the government,” he says. “They all seem to worship Ayn Rand. They think they’re smarter than the judges, smarter than the IRS, and refuse to accept anything but the most literal interpretation of federal tax code.”

One former Global retailer, who spoke to Seattle Weekly on condition of anonymity and whom we’ll call John, remembers that the offshore seminars were attended by normal folks looking to get ahead—housewives and doctors, people trying to establish themselves with home-based businesses, John says. “But the higher you went up in the organization, the scarier the people got,” he says. “They had a lot of money to play with, and they wanted off the grid.”

“It was very much like a big-top tent, where they invited all the carny hucksters in the world to come pitch what they were selling,” says Bill Branscum, an IRS agent–turned–private investigator who has been on both sides of the Struckman case. Ten years ago he was hired by a client to conduct his own investigation of Global Prosperity International, and was later hired by Struckman’s attorneys to investigate allegations that the government had fabricated evidence.

“The Money Was Just Too Good”

The FBI describes the sovereign-citizen movement as “anti-government extremists who believe that even though they physically reside in this country, they are separate or ‘sovereign’ from the United States. As a result, they believe they do not have to answer to any government authority.”

Struckman now says that he’s not anti-government, and dismisses what he says were the government’s attempts to lump him in with militia types and other more outlandish members of the sovereignty movement. As proof, he cites Keith Anderson’s 1998 ouster from the Global hierarchy. “We had long been nervous that his views had become just too out-there,” says Struckman.

In 2004, Anderson was convicted of tax evasion and money laundering in a U.S. District Court in Seattle for his role in Anderson’s Ark, an offshore tax-shelter scheme that cost the federal government an estimated $120 million. As per sovereignty-movement philosophy, he represented himself. Upon being handed a 20-year sentence, Anderson did his best to paint the proceedings as a farce, calling Judge John C. Coughenour a fascist and proclaiming that he retained “all of my God-given rights as given by Yahweh.”

In his testimony at Struckman’s 2007 trial, Global CFO Daniel Andersen said that he never truly understood Keith Anderson’s byzantine arguments on the nature of personal sovereignty, but trusted assurances from Struckman and LaMantia that they were legit.

Neither LaMantia nor Andersen responded to repeated interview requests for this article. William Cohan, the attorney who negotiated Andersen’s plea agreement, said, “I think Dan would say exactly as he did in his testimony.” According to Cohan’s sentencing memo for his client, after realizing that the theories they’d been selling weren’t valid, Andersen wanted to stop. “But the money was just too good,” Andersen said.

Of course, both Struckman and LaMantia were zealots. At trial, LaMantia testified that both he and Struckman were signed plaintiffs in a 2004 lawsuit brought by We the People, an organization fronted by notorious antitax promoter Robert Schulz. And in July 2004, after the founders of Global had gone their separate ways, LaMantia and Struckman marched on IRS headquarters in a We the People antitax protest.

J.J. McNabb, who is writing a book on tax-avoidance scams like Global, says that Keith Anderson, Schulz, and Global exist in a nexus of weirdness where members of the so-called sovereignty movement and antitax protestors meet.

Starting in the mid-’90s, Schulz built a tax-denier network of self-taught legal scholars and former IRS agents. In 2000, the group took out a full-page ad in USA Today urging the federal government to release the “basic proof” of its legal authority to collect income tax. It was from these small antitax protests that the modern Tea Party movement grew, says McNabb. But this political phenomenon has largely rejected the tax-deniers and the ideas they champion, he says.

Mark Potok, a spokesman for the Southern Poverty Law Center in Montgomery, Ala., agrees. “The only real remaining market for the kinds of ideas that Global Prosperity was hawking is among the sovereignty movement.”

Potok says hard numbers on the sovereignty movement’s actual size are hard to come by. The FBI, which tracks the movements of extremist groups, did not respond to a request for an interview for this story. But in a 2007 article published in the Journal for the Study of Radicalism, Syracuse University Professor Michael Barkun writes that the sovereignty movement is “a stubbornly resilient subculture, a community of the alienated unlikely to disappear any time soon.” And it hasn’t.

Andrew Steven Gray, a Monroe man with alleged ties to the sovereignty movement, was arrested in April 2009 after an FBI search of his storage unit turned up a cache of 21 firearms, two bulletproof vests, and around 9,000 rounds of ammo. Through his attorney, Gray later claimed that he’d distanced himself from the sovereignty movement. But the sovereignty movement wasn’t done with him.

A letter from a Snohomish man named Thom Satterlee was sent to the court on Gray’s behalf. In it, Satterlee—who on the record had advocated that Snohomish County secede from the U.S. and rename itself Freedom County—wrote glowingly about Gray’s character. Gray would later plead guilty to gun possession charges.

Emptying Out the ATM

“Dave could sell a guy with no arms a wristwatch,” says John, the former Global retailer. His experience with Struckman began in 1997 through a newspaper ad. It was short on details, save for a few lines about “firing your boss” and “taking control of your financial destiny.”

Unemployed and lacking a high-school diploma, John had “tried a bunch of other home-based businesses, but none of them worked,” he recalls. “I was looking to get rich.”

The phone number led him to a local Global salesperson. Soon he was sitting inside a cramped office with a handful of other prospective recruits listening to a prerecorded conference call. The voice on the other end might have been Struckman’s; John doesn’t remember. Nor did it matter, ultimately. Make four figures per sale and pay zero taxes on your earnings, the voice said. And with that, John was sold.

John gave the Global retailer who had recruited him a cashier’s check for $1,250 for the audiotape series, and then struck out on his own. He bought from Pro-Step, the company Struckman had founded to generate leads. He listened to the prerecorded training seminars. And to his great surprise, he made a sale on the first day he tried. “I go from being out of work to making $1,000 a sale,” he says. “It was like finding a pot of gold.”

Struckman, too, was enjoying his newfound wealth. Judging from documents related to the investigation, federal investigators had reason to believe that Struckman kept large amounts of cash on hand in his Issaquah home, and $30,000 in gold at a Bank of America safe-deposit box in Renton.

According to court documents, his ex-wife Michelle—with whom he’d reconciled—would head to the bank to withdraw thousands of dollars in cash. Struckman went on wild spending sprees, say court documents, dropping hundreds, even thousands, at a time on jewelry, cars, and clothing.

“I make at least six figures a month,” he told an audience in 1999. The money was so good that Struckman couldn’t help but get his extended family in on the action. His brother, Robbie, began marketing, eventually starting his own antitax scam in Tacoma called IMF Decoder. (The company’s current owner, Sharon Kukhahn, was indicted on federal tax-evasion charges in April.)

John says he finally met Struckman at a Global II conference in Cancún. After the seminar had ended for the day, Struckman made good on a frequent boast that he could empty an ATM of cash, John recalls. Afterward, they went dancing at a local disco, where Struckman bought out the bar.

The Hidden Camera

According to his testimony, David Bowden knew from the beginning that Global Prosperity International was a scam. But that didn’t stop him from investing around $30,000 in a Global-recommended investment. Bowden, now a 62-year-old retired Boeing technician, began detailing Struckman’s cars in 1996. Back then, Struckman “was driving a beat-up pickup truck,” says Bowden. “And then within a few months, he started bringing these luxury SUVs to get detailed three or four times a week.”

Bowden says he was drawn by the prospect that Struckman could maybe, possibly, be legit. In what proved a fateful decision, Struckman asked Bowden to name a price for a 1932 Plymouth hot rod Bowden had restored. Bowden gave Struckman what he thought was the slightly inflated price of $30,000. Much to his surprise, Struckman showed up at his home garage a few days later with a wad of cash.

Sometime later, Bowden reinvested that money in a Global investment that he claims Struckman recommended to him. It was a lemon, and he lost the full amount. Struckman returned the money. But starting in 1998, Bowden began to pull Global documents from Struckman’s cars each time the entrepreneur brought them in to be detailed. Years later, Struckman’s lawyers would make an issue of whether Bowden had done so of his own volition, or because he’d been promised some quid pro quo from the federal government over a delinquent tax issue that Bowden now says he wasn’t aware of. Judge Takasugi later prevented Bowden from testifying at Struckman’s trial, citing the lingering question of whether investigators had cut him a secret deal in exchange for his testimony.

Meanwhile, John was being harassed by the IRS. It was 1999, and he’d taken the advice and become a product of the product, having decided not to pay his federally mandated tax for the third year in a row. Global’s leadership initially showed some support, he says—Struckman included. “I was their little success story,” he says. “The guy who didn’t have anything more than an 8th-grade education, but who was doing pretty well.”

John says that Struckman gave him $15,000 to help pay his legal fees. But the “we’re all in this together” attitude lasted only as long as it took him to seek a second opinion, he says. He consulted his own lawyer, and was informed that he didn’t have much hope of mounting a defense.

In September 2000, John was sentenced to eight months in federal prison for tax evasion. He also lost his investment, a total of $51,000, he says. After his release, John took Struckman, LaMantia, and Andersen to court, alleging that they had defrauded him by misrepresenting the validity of the antitax theories Global had sold him, and which he’d then sold to others. A federal court in Oklahoma eventually awarded him a judgment of $4.5 million after Struckman and the rest of the plaintiffs failed to respond to subpoenas.

Speaking of the suit, Struckman admits to making mistakes, but stops short of taking full responsibility for what became of his former customers. “Everyone makes their own choices,” he says. “That’s part of free enterprise. I understand why people would point the finger. If they get into trouble with the IRS, they say, ‘Well, this is what they taught me.’ But in the end, they chose to participate.”

According to John, there are hundreds of people with similar stories. And yet so far he is the only Global retailer to file suit against the company founders. It could be that these folks, whom one might only loosely describe as “victims,” are disinclined to speak out of embarrassment.

But there are others. If one event hastened Global’s fall, it was the 1998 48 Hours segment in which a CBS hidden-camera crew infiltrated a Global conference in Cancún. The report detailed the death of Russell Anderson, a Montana man who hung himself after losing his retirement money in Global investments.

On April 5, 2001, this report was referenced frequently during a meeting of the Senate Finance Committee on the government’s response to tax-avoidance scams. Four years earlier, IRS commissioner Charles O. Rossotti had been called by the committee to take questions addressing the IRS’s thorny relationship with American taxpayers. Afterward, President Clinton signed into law legislation aimed toward making the agency friendlier.

This time, Rossotti was called in to address accusations that the agency had not been aggressive enough in investigating tax-avoidance-scheme promoters. Pushed for hard numbers on how many antitax organizations were in operation, Rossotti estimated “thousands.” Following the hearings, the IRS Criminal Investigation division embarked on a campaign to put higher-profile tax-scam promoters behind bars.

A decade later, hard numbers on how many scams are still operating are hard to come by. The primary government agencies involved in that effort—the IRS and the Department of Justice—both declined requests for interviews.

Author McNabb says there will always be people trying to exploit other people’s anger to sell crackpot tax-avoidance theories. “Part of it is that these people need a bogeyman, and taxation is a convenient one,” he says. “Most people would get tired hating and distrusting all the time. For them it’s fuel.”

For his part, Struckman says he has no plans to get back into antitax promotion. Post-release, he plans to visit family in Idaho and Washington, and work to pay the back taxes he still owes. But even if he wanted to, he cannot ever again make money selling his theories on the U.S. tax system, he says. Struckman claims that shortly after he was indicted, federal prosecutors filed a permanent injunction barring him from publicly promoting tax evasion.

To Struckman, it’s just one more example of the government treading on his constitutional rights. His lawyer, Bernhoft, writes in an e-mail that beginning with the passage of the Tax Equity and Fiscal Responsibility Act of 1982, the federal government began to issue civil injunctions against promoters of offshore tax schemes. Bernhoft calls the injunctions “patently unconstitutional,” lamenting that the “system’s goals and strategies always take precedence over mere constitutional rights and principles.” But if the federal government ever did file such an injunction against Struckman, it doesn’t appear anywhere in his legal records.

Still, Struckman remains convinced that he’ll prevail against the government in his appeal, and in regard to the purported injunction. How does he know? The truth is in his now-favorite Bible passage,Isaiah 54:17, which contains a short but defiant line about how no weapon formed against the faithful shall prosper. Struckman says he’s been clinging to this verse since arriving at SeaTac Federal Detention Center from Panama nearly five years ago. “My faith,” he says, “is the one thing that the government hasn’t been able to take away.”