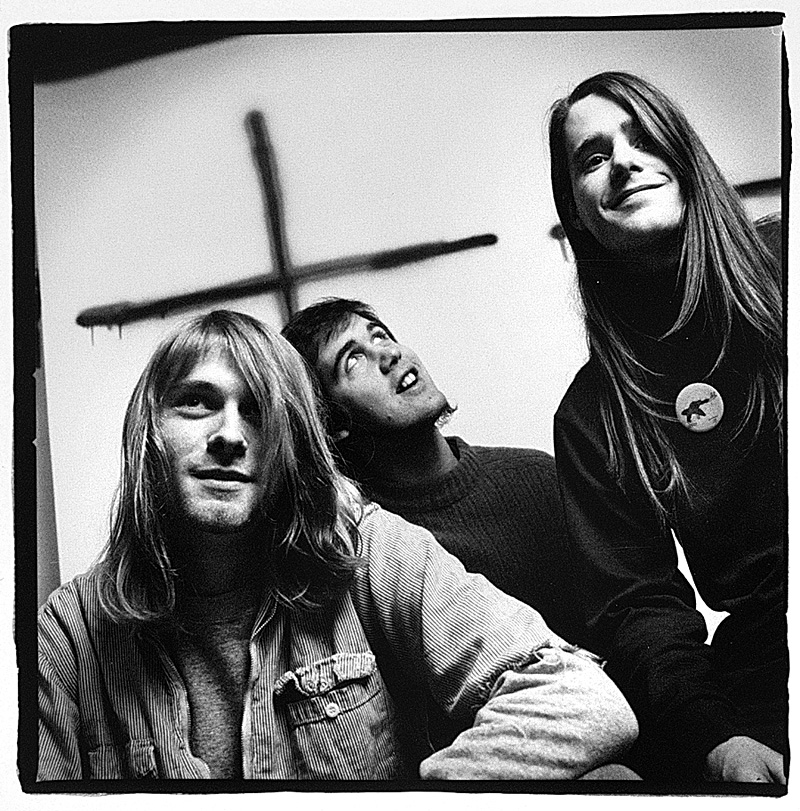

Nirvana was the opening act for Tad and Mudhoney at Sub Pop’s first Lame Fest on June 9, 1989, at the Moore. Just a year earlier, it would have been unimaginable that three local acts could fill the venerable theater. But the show drew a packed house of music fans thrilled to cheer on their friends. Nirvana duly rose to the occasion, trashing the instruments they could ill afford to repair, Kurt Cobain whirling his guitar around his head with such force it got tangled in his hair. Attendees got the chance to buy an advance copy of Nirvana’s debut album, Bleach, on white vinyl (currently valued between $400 and $600—as much as it cost to record the album originally). Drummer Chad Channing even proudly noted that the show’s flyer was the biggest one he’d ever seen the band’s name on.

The next morning, it was back to the grind. Nirvana drove down to Portland to fill in for Seattle’s Cat Butt in a show at the Blue Gallery for an audience of 12. Things weren’t much better on the band’s subsequent U.S. tour, which found the trio sleeping rough and forsaking regular meals to have sufficient funds to buy gas to take them to their next gig. Just days after the event that Sub Pop had billed, with typical hyperbole, as “Seattle’s lamest bands in a one-night orgy of sweat and insanity!”, the possibility of success on a large scale seemed as remote as ever.

Nirvana could have slipped into permanent cult status—just another band consigned to used-record bins, awaiting rediscovery. The stress of a grueling European tour in the fall of 1989 led to Cobain threatening to quit the group, for the first time disparaging the band’s growing audience as “fucking morons.” In May 1990, Nirvana lost Channing, and it took four months to find a permanent replacement.

Bleach is celebrated today less for what it is than for what it represents—the first album from a band that went on to find astonishing, and unexpected, fame. At the time of the album’s release, there were few signs of what would follow. Nirvana had been around longer than either Tad or Mudhoney, but were still third on the bill at Lame Fest. When British music weekly Melody Maker sent a reporter and photographer to Seattle to cover the burgeoning music scene, Mudhoney was given a two-page spread while Nirvana’s career was summed up in a somewhat condescending paragraph. (If they weren’t in the band, writer Everett True told readers, the members would be pursuing such lucrative careers as “working in a supermarket or lumberyard or fixing cars.” True later revealed the quote had come entirely from Sub Pop co-founder Jonathan Poneman.)

And other bands were starting to climb out of the indie realm and into the arms of major labels. In 1989, those who leaned toward the metal side of the punk/metal hybrid that came to be known as “grunge” were faring better. Mother Love Bone, formed from the wreckage of Green River (the rest of whose members had formed Mudhoney), goosed up the glam via their charismatic frontman, Andrew Wood, and landed a deal with Mercury. Soundgarden, the “thinking man’s metal band” whose wailing lead vocalist Chris Cornell prompted inevitable comparisons with Led Zeppelin, signed with A&M. Alice in Chains dropped its speed-metal affectations, added a noticeable streak of darkness to its music, and was picked up by Columbia. It seemed Nirvana was being left behind.

Listen to Bleach alongside Mother Love Bone’s Shine, Soundgarden’s Louder Than Love, Tad’s God’s Balls, and Mudhoney’s self-titled album, all released in 1989. There are some decided similarities, chiefly the pounding drums and crushing guitars. Each band was also fortunate to have a distinctive lead vocalist. But of the five, Nirvana is the band still looking to find its own voice. Most listeners point (correctly) to the melancholy “About a Girl” as evidence of the band’s penchant for tuneful pop, but few comment on how it also reveals the expressiveness of Cobain’s voice, so often buried amid the squalling noise on the rest of Bleach. Nirvana’s pop quotient was always their stealth weapon; the hooks that run through “School,” “Negative Creep,” and “Blew” were just waiting to be fleshed out, developed into the sound that would ultimately explode in the mainstream consciousness.

In the end, Bleach was an album that clearly indicated Nirvana’s potential. What was not known, or even much considered, was whether that potential would ever be fulfilled. When it was released, despite growing outside interest, wider-ranging tours, and major-label deals, it still felt as though we had the kind of small-town music scene where everyone knew each other. It was still easy to sit down with your favorite band after their set at the Central, or run into them at Cellophane Square, selling off their record collections to help pay the rent. For all its promise, Nirvana’s story could have ended with Bleach. Instead it now stands as a poignant reminder of a band’s first steps on the national stage, when all the possibilities were still endless.