Much like Bob Marley’s towering stature in the world of reggae, it is impossible to listen to Afrobeat without encountering the mythic figure of Fela Kuti. Like Marley, Kuti is regarded as the patron saint of his art form, and his deity-like presence still permeates the music. In some ways, Kuti’s shadow looms even larger than Marley’s, as Kuti is universally regarded as the inventor of the genre. Kuti himself coined the term “afrobeat,” which is still synonymous with his name for many listeners across the globe. As the genre continues to swell in popularity, it is all too tempting for audiences to view it as a form frozen in time, forever lorded over and defined by its eternal father figure.

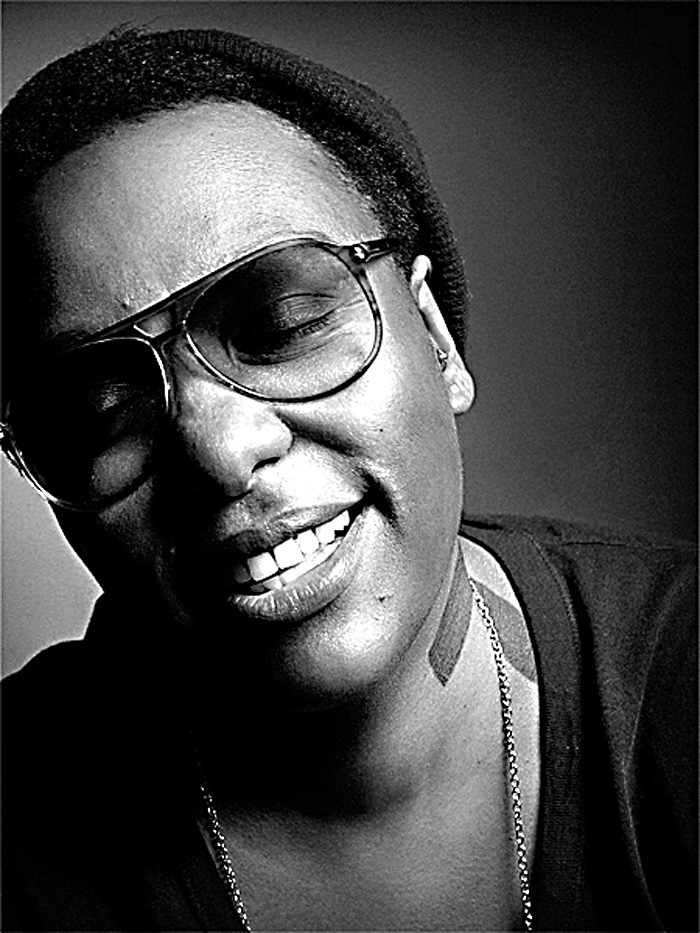

One would expect that the pressure on Fela’s oldest son, saxophonist Femi Kuti, would be tremendous. But unlike most offspring of musical giants (see Coltrane, Lennon, Dylan, and the aforementioned Marley), Femi seems to have his father’s burden comfortably in check. If the younger Kuti is, in fact, shouldering the baggage of his father’s accomplishments, he handles it with the agility and grace of one of his dancers. At the very least, it hasn’t crushed his resolve to make music, and that itself says a lot. Femi has taken it upon himself to bring afrobeat up to date, and it’s to his credit that audiences must now view the form as a living thing, with fresh potential and an enduring capacity for growth and adaptation.

Like Fela’s work, the junior Kuti’s music is filled with the hallmarks that make afrobeat such a celebrated genre in the first place—above all, groove on such a scale that a listener almost has no choice but to get enveloped in its powerful hypnotic pull. Since Femi actually played with his father, and even served as Fela’s band director in the ’80s, he has not made his creative decisions from a position of reverence. His are not the musical moves of one who feels awed, overshadowed, or otherwise confined by the parameters that Fela stamped on the music. He has, for example, introduced hip-hop, soul, and jazz elements to afrobeat and featured them prominently, as demonstrated by his collaborations with rappers like Common and Mos Def and his signing with Motown for his self-titled 1995 album.

Femi has also been clear in his insistence on playing shorter songs. Fela concerts were legendary for how drawn-out one piece of music could get, with the band sometimes working one groove for up to an hour straight.

“It wasn’t difficult to play for that long,” explains Femi on an overseas call from his home base in Lagos, Nigeria, “because many people in the band would take extended solos. You could sit there and listen to everybody improvising. But that wasn’t where I wanted to go.”

Femi remains adamant about focusing afrobeat’s groove, reeling it in, and retaining its potency in a tighter form. In a sense, he has done the same with the music’s political aspect. Like Fela, Femi’s music contains a sharp activist slant. Both musically and by other means, he directly addresses post-colonial Africa’s ongoing struggles, government corruption, and the problems wrought by the prevalence of oil in Nigeria. While his work pulls no punches—”You better ask yourself why the richest continent get the majority of the poorest people” commands the back cover of his most recent album, 2008’s Day By Day—his diplomatic touch only bolsters his message. On the album, as in previous work, Femi calls for both peace and revolution. “We work and pray for peace to reign,” he sings on the album’s title cut, and with the simple addition of the word “work,” the lyric carries 10 times the weight of your typical song about peace and love.

It’s no surprise that such sentiments don’t ring hollow coming from a guy who, much like Fela was, is routinely under government pressure that sometimes turns violent. He’s well-acquainted with the ire of the Nigerian government. The Shrine, Femi’s reincarnation of his father’s nightclub, was allegedly attacked by government militia armed with knives and baseball bats last year. The venue doubles as as a meeting place for activists and a housing center for homeless dissidents. On May 25 (days before his interview with SW), the club was cited for a noise violation and shut down the next day. The Kuti family asserts via press releases that both instances came as “retaliation for the criticism Femi has launched, in posters all over Lagos, calling for the return of electricity in his impoverished neighborhood and inciting his neighbors to revolt against the ever-deteriorating conditions prevalent in their increasingly precarious lives.”

Even with all this going on in Femi’s life, audiences should still expect a great time. The underlying urgency will likely strengthen the groove of his band, Positive Force. Femi, a firm believer in the power of music to elevate consciousness, cites (both on the album and in conversation) Miles Davis and Coltrane as examples of artists who raised awareness without even using words. Coming from someone like Femi, who has long steeped himself in his country’s hardships, this serves as a stark reminder—to American listeners in a culture that has flattened music into simple entertainment—of the role of art.

“Everybody has to play his part,” says Femi, urging people to start organizations of their own. “Lawyers, doctors—everybody.”

Including Femi’s 14-year-old son, Madé. As Femi did, Madé Kuti plays saxophone in his father’s band. But Dad is letting his son forge his own path.

“I’m not hard on him,” Femi explains. “He plays when he wants. If he doesn’t feel like playing that night, I don’t trouble him. I don’t want to put the burden of a 40-year-old man on his head. Because then when he gets to 40, he will have nothing to do. I want him to have his youth. He has to go to school, mix with his mates, play football, and run around.”

Perhaps Madé will follow his father’s lead and push afrobeat to places it hasn’t been, perhaps not—but in the meantime, the future of afrobeat looks secure as Femi carries it into the 21st century.