Dave Osgood remembers his enthusiasm when Tom Carr first ran for City Attorney in 2001. “He was a new face, a fresh voice,” says Osgood. “He seemed to be open to discussion and reason.”

Those were qualities that Osgood, an attorney who frequently represents nightclubs, says were missing from the approach of then-reigning City Attorney Mark Sidran, Seattle’s answer to Rudolph Giuliani, the New York mayor who waged war on low-level street crimes. Sidran ranks as one of the most controversial city figures of recent years. He promoted a set of “civility laws” that criminalized aggressive panhandling, lying on downtown sidewalks, and other quality-of-life nuisances—laws that inflamed some homeless advocates. And he tried to stop drug dealing and violence around predominantly African-American clubs by shutting them down through a law that allows for the “abatement” of dangerous establishments.

Carr was then a commercial lawyer best known as the chair of a citizens’ council charged with building the ill-fated monorail. In the city voters’ pamphlet and elsewhere, he pitched himself as someone who would “take a more moderate approach” and act as a “mediator.”

But after Carr took office, “I rapidly found that I was missing Mark Sidran,” Osgood contends. As he sees it, Carr also went after clubs—masterminding the sting operation known as “Sobering Thought”— but did so “in a very passive-aggressive fashion.”

“In retrospect, Mark was great,” Osgood says. “He would say, ‘Hey, Dave, here’s a knife that I’m going to wield precisely this way.’ You knew what he was doing. With Tom, you have to turn your back and wait.”

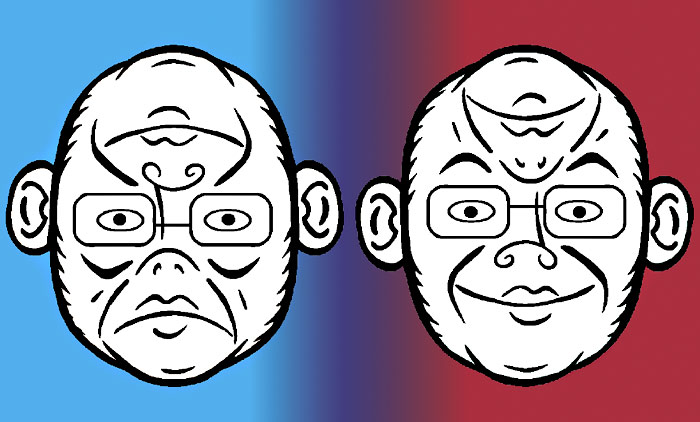

It’s an extreme characterization of the man who is now facing a heated campaign in his quest for a third term in office—he sailed into his second term unopposed. But it’s one that gets at the two sides of Carr that make him something of a puzzle, especially compared to his predecessor. “Mark was so strong and clear in his statements,” says City Councilmember Nick Licata. “Tom is more nuanced.”

The 52-year-old Carr has a hulking frame. Balding and bespectacled, he avoids the limelight that Sidran embraced, often speaks in measured tones, and can wax thoughtfully and compassionately about the problems of the homeless and addicted. His signature achievement in office has been the creation of a new court that attempts to help defendants, through access to social services like drug treatment and housing, rather than jail them.

Yet Carr can verbally pounce on critics too. As Licata puts it, he has at times a way of drawing “a line in the sand” that has given him a reputation as a stealth law-and-order man—tough, unyielding, and resistant to attempts by the press and public to examine the details of city business.

As in all puzzles, the two sides fit together. But to see that, it’s helpful to know where Carr came from.

Bob List met Carr at New York Law School (not to be confused with neighboring New York University). They went to night school, not the more rarefied environment of day classes. Students of List and Carr’s ilk needed to work during the day; they didn’t come from privilege. List worked as a paralegal, Carr as a computer programmer for Metropolitan Life Insurance Company.

“Of all the backgrounds of all the folks,” says List, who became a close friend of Carr, “Tom came from the most modest.”

Carr hails from New York City’s rough-and-tumble south Bronx, part of a big Irish-Catholic family who squeezed into a one-bedroom apartment. His parents slept in the living room on a pull-out couch. His sister unfurled on a daybed in the hall. He and his two brothers took the bedroom, for a long time sharing a single bed. The three boys formed an upside-down “T” with their bodies, Carr and one brother sleeping lengthwise and the other sleeping crosswise at the bottom.

His mother was a stenographer for Metropolitan Life, where Tom later found employment. His father “didn’t do very much,” Carr says. “My dad was an alcoholic.”

“He was a big guy, like me,” Carr adds. “At 17, he volunteered for World War II. He had his 18th birthday in a place called Anzio [an Italian beach town that became a battleground], served throughout the entire war, and came back and drank a lot.”

One day when Carr was 14, he watched his father head to a party. It was a noteworthy sight: His dad was sober. But he drank too much at the party and fell down a flight of stairs. The accident was fatal. His mother gamely took up the challenge of raising the family on her small salary. “She got three of us through college,” Carr says.

Despite all this, Carr remembers his childhood as “idyllic.” Living among large apartment blocks full of hundreds of families, he was surrounded by friends. But when asked how his background shaped him, he circles back to his father. “Having lived up close with what alcohol does, and now seeing all the defendants I see who are addicted to alcohol, it does shape my desire to try to help folks with addictions,” he says.

Laughingly pointing out that his middle name is Aquinas, Carr acknowledges that his views on such matters are also influenced by his “17 years of Catholic education,” culminating in a B.A. from St. John’s University. He says he believes in redemption: “Nobody is too far gone to save themselves.”

It is worth noting, though, that in Catholic theology redemption is not a free ride. “The other side of redemption is the concept of atonement,” says Mark Markuly, dean of theology at Seattle University. “For people to appropriate redemption, they have to confess their sins and seek to make amends.”

In the secular context of the courtroom, Carr has always held to the notion that “it’s important for people to take responsibility for their actions. It’s the first step to changing your behavior.”

Carr talked throughout law school about his interest in public service, List recalls. A few years later he got his first stab at it, handling conspiracy cases against organized crime for the U.S. Attorney’s office in the Eastern District of New York.

He switched to the private sector when he moved to Seattle in the early ’90s, working for a decade at the long-established firm Barrett Gilman & Ziker. At the same time, he became active in West Seattle Democratic circles, befriending Greg Nickels. In 1994, Carr attempted to get back into public service by running for the state legislature against longtime representative Georgette Valle, losing by less than 400 votes. Four years later, he was appointed to the Elevated Transportation Company Council, which was charged with getting the monorail off the ground.

Carr had his doubts about the project. “I was startled when Tom told me he didn’t think this thing would go,” says fellow ETCC member Dick Falkenbury, the taxi driver who famously drafted the first monorail initiative on the back of a napkin. But Carr accepted the appointment anyway, believing that Seattle, like New York City, “should control its own transportation destiny.”

Eventually, Carr became a monorail believer, and Falkenbury credits him for a “huge turnaround.” In the end, of course, costs exploded under the subsequently-formed Monorail Authority, and a 2005 advisory vote killed the once-popular idea. By that time, Carr had long since moved on to the City Attorney’s office.

When he took over, the battles of Sidran’s tenure were still raging. The city was locked in a standoff with El Centro de la Raza, which was hosting Tent City in violation of building codes. Sidran tried to force Tent City out, and the matter went to court. According to Ted Hunter, an attorney for SHARE/WHEEL, the organization behind the homeless encampment, the city refused to negotiate. “It was all just fight and bluster,” he says.

Right after Carr took over, though, Hunter says he got a call from the City Attorney’s office, which wanted to talk. “There was a significant change of culture,” Hunter says.

Carr says he did his homework before the election, and realized Tent City was “a pretty good operation [with] a strict disciplinary code. What we needed to do was put it in writing.” Carr’s office and Tent City hammered out a consent decree that allowed the encampment to exist provided that certain requirements, including health and safety inspections, were met.

The City Attorney’s approach toward Tent City was consistent with his emphasis on “the importance of putting a warm and dry space around someone who’s troubled,” even if it’s just a tent. Carr also championed the once-controversial wet-house for alcoholics known as 1811 Eastlake, notes Bill Hobson, executive director of the Downtown Emergency Service Center, which runs the facility.

Another inherited flashpoint issue shaped Carr’s reputation more, however. In 2004, the City Council deliberated over whether to repeal the Sidran-initiated vehicle impound ordinance, which allowed the city to impound the cars of people caught driving with a suspended license due to unpaid traffic tickets. Opponents argued that the law disproportionately affected African-Americans and the poor. Carr strongly lobbied in favor of keeping it.

Lisa Daugaard, deputy director of The Defender Association (TDA), a public defense group that opposed the ordinance, saw Carr’s stance as an about-face. “He campaigned on the need to amend the impoundment law,” she says.

“I never opposed impound,” Carr counters. “I may have talked about evaluating its effectiveness.” He says he came to learn that people with suspended licenses were involved in more accidents than others were. He also argued that taking their cars was not as harsh as locking them up, the tactic previously employed by the city.

The Council repealed the law over Carr’s objections. The City Attorney was left looking like a less-effectual version of Sidran, who, despite all the controversy surrounding his tenure, had succeeded in getting his laws passed. Soon after, though, Carr launched his plan for dealing with quality-of-life crimes, and it looked very different from Sidran’s.

At the time, so-called “community courts” were popping up around the country, a new approach to dealing with low-level offenders who were continually cycling though the criminal justice system. Rather than locking them up, such courts attempted to hold them accountable by other means, usually through community service requirements, and to deal with their underlying problems by connecting them with social-service providers. Seattle’s Downtown Neighborhood Association was talking up the idea, and Carr got behind it.

Carr recalls one epiphany that led to this decision. “I remember the first time I went to watch the jail calendar,” he says, alluding to a period of time set aside for a series of jailed defendants to come to court to make their pleas. “These people are sick,” he recalls thinking of defendants burdened by mental illnesses and addictions, along with homelessness and abusive pasts. “What are we doing?”

He contacted Dave Chapman, then executive director of the Associated Counsel for the Accused (ACA), another group of public defenders who work in Municipal Court, to discuss the idea, which led to a series of talks between the two men and then-Presiding Judge Fred Bonner. They later brought in other constituents. “Tom was very, very good at getting input and listening to what other people had to say,” says Chapman.

Carr didn’t seem too interested in the input of the more activist-minded Defender Association, however. The organization objected to the community-court concept because it abandoned the traditional role of defense attorneys. Rather than fighting their clients’ charges, the courts asked them to sign off on sentences—albeit ones that did not involve incarceration as long as certain conditions were met—that everyone was supposed to agree were in defendants’ best interests. That meant, at least in Seattle’s Community Court, which began in March 2005, that defendants pled guilty. It was something TDA vociferously opposed, but which Carr, with his belief that people need to take responsibility for their actions, insisted upon. Siding with Carr, the mayor’s office went so far as to marginalize TDA’s role in Municipal Court for a time because of its failure to get on board with Community Court. (See “The Defense Can’t Rest,” SW, Jan. 30, 2008.)

With the certainty of a charge on their record, however, about half of the nonviolent offenders eligible for Community Court ended up declining participation. So in mid-April, at Carr’s behest, Community Court started granting “dispositional continuances” to defendants. That means that charges against them are dropped if they complete the conditions of their sentence: 16 hours of community service for first-timers in the program, and contact with some kind of social-service provider.

Seattle’s Community Court is considered a national model, in part because it’s made efficient use of a shoestring budget, according to Julius Lang, director of technical assistance for the Center for Court Innovation, a New York think tank. The center, along with the federal Bureau of Justice Assistance, picked the Seattle court to be one of three “mentor” community courts around the country, providing assistance to others.

Yet a 2007 evaluation reported that just 32 percent of Community Court defendants completed their sentence requirements. The report, written by the Denver-based Justice Management Institute and commissioned by the court, also noted that a study of 66 Community Court defendants found that they reoffended at a slightly higher rate than those who go through traditional court.

One likely reason, according to the evaluation: The court’s defendants are some of the toughest cases, carrying extensive criminal histories and multiple problems such as homelessness, mental illnesses, and addiction. And while the court requires defendants to make “contacts” with social-service providers, it doesn’t actually have the resources to ensure that they actually receive services.

Carr, who maintains that the court has “changed lives,” says that his office is in the process of doing a more detailed study that he believes will show more encouraging results. He divulges that he also recently talked to court officials about applying for federal stimulus money to start a “treatment court” for addicts, similar to King County’s Drug Court. He says the court agreed, provided that he can find additional funding not just for the court itself (which the stimulus money would cover), but for the treatment as well.

While his attitudes toward drug and treatment courts reflect a nuanced and flexible approach, he has staunchly resisted any suggestion of easing up on drug enforcement outside of those venues.

In 2003, he opposed I-75, which called for Seattle police to make marijuana enforcement their lowest priority. He warned that it was tantamount to legalization, an idea that makes him bristle. “You need prosecution,” he says. Taking responsibility for your actions may be the first step toward transformation, but in Carr’s view, most people need an incentive: the threat of incarceration. Voters passed the initiative anyway.

The City Attorney also voiced concerns when the latest budget shortage led elected officials, including county prosecutor Dan Satterberg, to put forward more lenient drug policies to save money. Carr’s own policies in municipal courtrooms have prosecutors recommending considerably stiffer sentences for drug- and alcohol-related crimes than do prosecutors in District Court, which handles misdemeanor offense outside the city, according to current Associated Counsel for the Accused executive director Don Madsen. For instance, Carr’s prosecutors might recommend 45 days in jail for defendants charged with driving under the influence in cases where county prosecutors would recommend only one.

Carr’s motivation is simple. “DUI is dangerous,” he says.

Operation Sobering Thought represents perhaps Carr’s sharpest line in the sand. Two years later, there’s still some confusion about how the 2007 sting operation came about. Clearly Carr was involved, but was the mayor too?

“What we thought was happening was that there was an attempt to create a media sensation that would get one of Nickels’ laws passed,” says Osgood, the club lawyer. The mayor at the time was urging City Council to pass a “nightlife ordinance” that would require clubs to get a special license, one that could be revoked if they didn’t prevent violence from occurring around their establishments.

Tim Hatley, a lobbyist and old friend of Deputy Mayor Tim Ceis, says that, to the contrary, he heard that City Hall was “stunned” to learn about the sting. “He was clumsily trying a political play,” says Hatley of Carr.

Regina LaBelle, the mayor’s legal counsel, says only that the operation “was something Tom did on his own with the police department.”

Carr confirms this account. During the summer of 2007, Carr says he’d been hearing from police that they were having a problem at closing time with violence outside clubs. He tried to get the Washington State Liquor Control Board to pull the license of one problem establishment. The board said it didn’t have the evidence to do so. Hence, says Carr, “I started exploring with my folks a way to get the evidence the Liquor Board was looking for.”

City Attorney staff and police then came up with a scheme, Carr says. Over a period of weeks, police sent two young women with fake IDs to bars to see if they could get in. “The rumor was that if you were a pretty girl, you could get in anywhere,” Carr says. Police also got others to attempt to smuggle in guns. Both schemes succeeded, particularly the pretty girls. Late one Saturday night in October, police swooped down on 14 clubs and hauled 17 employees to the West Precinct; 13 additional employees were later charged.

The episode startled bartenders and doormen, who were cuffed and booked rather than issued a citation.

“If you have an issue with nightlife, you sit down with the industry,” says Osgood. “You don’t go and entrap bartenders.”

City Council member Sally Clark, who voiced some concerns about nightlife violence at the time, criticizes Carr’s handling of the issue as over-the-top. “If you want to say ‘Hey, look, we did catch you and we’re going to issue a fine,’ so be it,” she says, adding that the idea of putting bartenders in jail struck her as out of line. She also questions the wisdom of having the city enforce regulations that are under the Liquor Board’s jurisdiction, and the cost of doing so—$53,000 in police time. “I don’t know that was the best use of resources,” adds Clark.

Carr defends the operation, which he claims revealed the extent of problems in the industry. “That’s what gets lost in all this,” he says, noting that the underage girls used as police decoys got into 14 of the 15 places they tried. But are such girls really responsible for the after-hours brawling that was the supposed cause of concern? Whatever valid public-safety concerns the city had were buried beneath an outpouring of hostility over the tactics used.

In the end, the stiff penalties Carr sought failed to materialize. One case resulted in a not-guilty finding, and most of the others were resolved with a dismissal—as in one case where police nabbed the wrong bouncer— or dispositional continuance.

Today it’s hard to find anyone outside the City Attorney’s office who will speak favorably of the operation. Even Carr’s own campaign manager, a onetime bar manager named Cindi Laws, says she disagreed with him on the matter, citing the jurisdictional conflict. (Police Chief Gil Kerlikowske, recently nominated by the Obama administration to the post of national drug czar, declined to comment.)

The one thing the operation did accomplish, though, was to thoroughly alienate the nightlife industry from the City Attorney. “Mr. Carr’s got some sort of bizarre antipathy toward public drinking,” concludes Gus Hellthaler, owner of the Blue Moon Tavern. Although he was not caught in the sting, he faced his own showdown with the City Attorney in 2006 over a “Good Neighbor Agreement” Carr wanted him to sign. The lengthy contract included a provision that would have required Hellthaler to hire off-duty police officers. “It seemed like a backdoor way of being shaken down,” he says. When he refused to sign, Carr’s office filed an objection with the Liquor Board to a renewal of his license. The mayor’s office, rather atypically, played peacemaker, and Hellthaler eventually signed a much-abbreviated version of the agreement. (See also “Strange Boozefellows,” page 8, and “Full Moon Fever,” SW, June 14, 2006.)

In spite of this, Carr’s office continues to press Good Neighbor Agreements on clubs. Osgood, who defended the Blue Moon and others in the matter, says it is standard operating procedure for the city to demand that a nightlife entrepreneur sign one—or else have his or her liquor license held up by a city objection. Carr retorts that it is not standard, but that he likes such agreements because “they are parameters for behavior.” His office has persuaded 24 establishments to sign them in the past two years, according to city records.

“It’s blackmail, is what it is,” says Troy Selland, co-owner of Fusion, a University District club. He says he was led to believe he wouldn’t get a license unless he agreed to a seven-page document, so he signed it in the fall of 2007. Among other measures, it compels him to maintain security cameras, monitor the surrounding neighborhood, and limit occupancy. On the basis of Fusion’s record, which includes a violation and several written warnings from the Liquor Board for disorderly conduct, the city is now objecting to Selland’s pending license application for a pizzeria he wants to open in Belltown.

These standoffs may soon become less common, however. At the Liquor Board’s request, the Legislature just passed a law to enable the Board to issue a special nightclub license allowing local jurisdictions to petition for restrictions like a Good Neighbor Agreement. It might sound like a controversial resurrection of Nickels’ idea, but in fact many clubs are behind it because it gives the Liquor Board a role in reviewing and enforcing such restrictions. “They’d rather have a neutral third party than the city coming in and regulating,” says Hatley, who testified for the bill on behalf of the Seattle Nightlife and Music Association.

Pete Holmes, Carr’s opponent in the City Attorney race, has been seeking support from the estranged nightclub industry. Of Sobering Thought, Holmes notes the outcomes of all the cases and asks “So what did it accomplish in the end?” Although he calls Community Court a “positive step,” Holmes draws attention to Carr’s harsher stances on low-level drug and DUI crimes, contending that such offenders don’t necessarily need to go to jail.

Holmes’ most persistent campaign theme, though, revolves around transparency. Carr recently got some good press on the issue when he voiced concern in The Seattle Times about a series of private meetings held last month between the mayor and small groups of council members. But Carr has often veered in the opposite direction.

Among lawyers, Carr is renowned for the 2004 state Supreme Court case known as Hangartner v. City of Seattle, in which his office successfully argued that public agencies should not be required to disclose communication between them and their attorneys. Previously, the exemption had concerned only documents that related to ongoing or expected litigation.

The case is one reason Greg Overstreet, a lawyer who previously served as the state Attorney General’s ombudsman for public-disclosure disputes, says he called Carr a “polarizing figure” when in 2007 Governor Christine Gregoire picked him to head a “Sunshine Committee” charged with reviewing exemptions to the state’s Public Records Act.

The AG’s current ombudsman, Tim Ford, also serves on the committee, which is ongoing. He says Carr opposed the suggestion that the committee advise the Legislature to reverse the Hangartner ruling. “It was one of the few times he cared enough to weigh in,” Ford says, noting that Carr, as chair, often doesn’t vote or voice his opinion. The committee nevertheless voted to recommend a reversal last year.

Carr’s office also subpoenaed three Seattle Times reporters in 2007, asking them to reveal confidential sources for a story, on police misconduct, that had led to a lawsuit against the city. It was a highly unusual move, made all the stranger by the fact that the Legislature had just passed a Shield Law that protected reporters from having to disclose sources. As soon as the Times ran a story about the subpoenas, Carr withdrew them, according to the paper’s lawyer, Bruce Johnson.

Carr contends that he hadn’t known about the subpoenas in advance. But he also defends them, saying they were not what they appeared to be. “It was a matter of formality,” Carr says. “We wanted to know what [Times staff] were going to do if they were called into court to testify. Invoking the [shield] privilege was better for us.” If the reporters instead named city employees as their sources, that would hurt the city’s case. Not finding out the Times’ response “would seem like malpractice,” Carr contends.

Overstreet, the former AG ombudsman, seems nonplussed by that explanation. “I think subpoenas to the media that are unlawful shouldn’t be used in some sort of game,” he says, adding that the Shield Law is there for a “very important reason: the First Amendment.”

Johnson says he certainly didn’t understand that the subpoenas were a formality. “It would have been nice to know that they were playacting,” he says now. (Last December, the city settled the suit for $12,000. Plaintiffs had been seeking $6 million.)

This is all fertile ground for Holmes’ campaign. But his clarion call is another, more personal experience. In 2002, Holmes, then a bankruptcy lawyer, was appointed to a new citizens’ board charged with reviewing the work of the disciplinary office with the Seattle Police Department, known as the Office of Professional Accountability (OPA). Licata says he opposed Holmes’ appointment. “I thought Pete was going to be a white-collar stick in the mud,” he says.

But Holmes, as Licata notes, proved otherwise. As chair of the board, he loudly decried a confidentiality agreement that the city had negotiated with the Seattle Police Officers’ Guild. The agreement prevented the review board from releasing a broad category of information that was considered confidential: not only officers’ names but details related to “investigative files.” It also prevented the city from indemnifying board members who released such information.

As it got ready to issue its first substantive report in 2004, which delved into individual cases but did not name officers, the review board asked the City Attorney’s office to confirm that the report did not violate the agreement. According to Holmes, an assistant city attorney said it did.

“We dumbed the report down not once but twice,” Holmes says, adding that even then the assistant city attorney refused to sign off on it.

Carr says what the review board was really looking for was for the city to waive indemnity, which it could not do by virtue of its agreement with the Guild. But after the board complainingly released its report anyway, Carr offered to try to find a workable resolution for future reports.

According to both Carr’s and Holmes’ accounts, the talks between the City Attorney’s office and the review board went nowhere. A low point occurred when Carr and Holmes appeared on City Inside/Out, a Seattle Channel show hosted by C.R. Douglas. To Holmes’ surprise, Carr went on the attack. He accused the board of stepping outside its scope by addressing individual cases, and of failing to do the job it was supposed to do—namely, publish statistics like the number of complaints and the percentage sustained.

He later repeated this theme in a letter to Holmes: “The vast majority of the information that you are required to report would be numbers,” wrote Carr. Relations remained rancorous until Holmes left the review board last year.

With such history, the two men clearly get under each others’ skins—a situation made all the more bitter by a campaign tangle that quickly popped up over Cindi Laws, an old friend of Carr’s. Holmes had hired Laws to be his campaign manager when he was thinking about running for City Council. When he switched to the City Attorney’s race, Laws defected to Carr’s campaign. Holmes reacted “as if I had left him for another man,” Laws says.

“Of course I was upset,” Holmes responds, questioning Carr’s ethics in luring away his campaign manager. Carr maintains he was simply “being loyal to a friend” in offering Laws a job when she decided she couldn’t stomach running a campaign against him.

The temper Holmes brings out in Carr suggests that during his re-election battle, the City Attorney will reveal himself to be a far more complex figure than the mild-mannered moderate he once seemed.

“The first I heard of Pete Holmes was when he was accusing me of suppressing a report I had never seen,” Carr fumes.

And yet for all the controversies Carr has been involved in, he remains in the public mind a somewhat fuzzy figure. To Osgood, that seems partly by design: “The less people know about Tom,” he says, “the happier he is.”

Carr is combative but not self-aggrandizing. The most conspicuous ornamentation in his office is not a plaque or political photo, but a row of Pez dispensers on his windowsill, a reminder of his 12- and 15-year-old sons. The first line on his résumé under “community activity”—above his tenure on the Elevated Transportation Company Council—is coach for the West Seattle Association of Pee Wee Baseball.

He regularly handles run-of-the-mill cases in Muni Court himself. TDA’s Daugaard recalls trying a couple of theft cases against Carr when he first took office. “Not every CEO would put himself in that position, where he was just another lawyer,” she says. Sidran didn’t, according to Chapman, who notes that he has even seen Carr show up in court on Saturdays and holidays.

Carr works most often in Community Court, and he was there on the day in mid-April that it began to grant dispositional continuances. He unobtrusively walked into court rolling the kind of cart favored by flight attendants and workaday lawyers, which was piled high with boxes of case files. When a curly-haired woman with sunglasses atop her head had her case dismissed, public defender Nancy Waldman (previously a Seattle School Board chair) hugged her. Carr sat quietly by. His main role was to impassively read out the names and case numbers of defendants, then sit by while Judge Ron Mamiya dealt with them.

Because prosecutors and defense attorneys have little to spar about in Community Court, it’s the judge’s show—and Mamiya hams it up. He prods defendants into emoting about what the court experience has done for them, and upbraids them—on this day, reducing a pregnant woman to tears—if they have not fulfilled their obligations. (Mamiya perhaps needs a talking-to himself, as he recently reached a $135,000 settlement with a court employee who claimed sexual harassment.)

So why does Carr come? It keeps him committed to Community Court and its defendants, he says. “Prosecutors always refer to people by their charge. When you see people behind the crimes, it affects how you deal with them.”

It also seems a matter of his temperament, which in some ways seems more suited to the formalized legal arena than the flashier political stage. Working in court, Carr says, “is the only thing I do that’s really just lawyering.”