Asking Jonathan Richman for insight into his music is like having to answer the Sphinx’s riddle. His tight-lipped awkwardness during interviews is legendary. Countless interviewers have tried playing Oedipus only to be denied entry into Richman’s head, and come away from the interview more baffled than before. Even getting an interview is difficult. If Richman consents, the interviewer must provide his or her phone number, then stay glued to the phone so as not to miss Richman’s call, which could come at any time–one flummoxed journalist conducted his clumsy conversation with Richman at two in the morning.

However, there are topics Richman will discuss: One of his most candid interviews was published not in a music rag, but in Herbivore, in which he talked about his mostly-vegan diet and environmentalist philosophies. The man refuses to discuss either his music or his personal life; for decades he’s been making journalists feel insecure, not only because of his flippant responses to our most thoughtful, sincere queries but because he seems utterly indifferent to what’s written or said about him.

But in a 1986 interview on long-dead MTV show The Cutting Edge, Richman offered a rare bit of insight into his views on the media: “I’m not understood that well by the press because I think they try and complicate it too much,” Richman said. “All you gotta do with this stuff, folks, is like it or not like it.” And ever since, that’s been the media’s dominant view of Richman: that he’s a simple songwriter (his seminal work with the Modern Lovers notwithstanding) who specializes in sweet, unsophisticated ditties about ill-fitting jeans, insects, and, most famously, a special lady named Mary.

But that too is misguided. A recent article in Cincinnati paper CityBeat called Richman “the eternally endearing man-child.” Endearing? Absolutely. Childlike? Not really. When music critics discuss Richman, they mistake his songwriting’s playful simplicity for childlike naiveté. Most of those writers loved him best at the helm of the original Modern Lovers, the seminal proto-punk band that made Richman a permanent fixture in the scattered history of punk rock. These writers—nay, fans—loved Richman as he was in the beginning, a bratty youth who expressed his precocious angst in songs dripping with mockery and cynicism. How could their hero, one of punk’s innovators, start writing such gentle folk songs about such seemingly trivial subjects?

Unfortunately, what music fans—including music journalists—have difficulty accepting is that their beloved artists are human beings who grow up and out of their previous selves. Throughout Richman’s career, he’s experimented with instrumentation, style and genre (remember Jonathan Goes Country?), and the language he chooses to sing in (Spanish, French, Italian, or Hebrew). What doesn’t change is this: Richman never forgets that to wax poetic is to overcomplicate. His songs are straightforward, yes, but they are not, as so many have assumed, without depth. Instead they reflect the poignant wisdom that the simplest way to state something is usually the best way. Richman’s songwriting reflects not a step backward, but the wisdom of a man who’s learned that profundity can be found in the smallest details, and to enjoy everyday pleasures as though they were rare and special. If he is childlike, it’s only in his boundless ability to view the mundane with a child’s fresh eyes. Salon‘s Chris Colin said it well: “His is a revision of the rules codified by the paragons of sophisticated rock music. Slouching over a whiskey is not depth. Morose discomfort is not depth. Depth is not depth. What’s deep—what’s truly deep—is ‘She Doesn’t Laugh at My Jokes’ and ‘When Harpo Played His Harp.'”

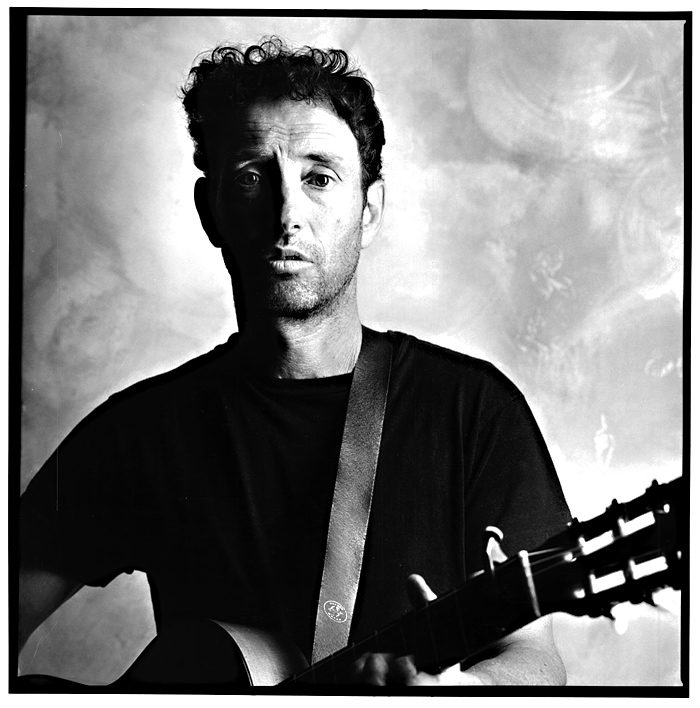

Richman’s wisdom is that he knows it can be very difficult to restore the original visceral reaction we had to a piece of music after we’ve unceremoniously critiqued and torn it apart. It’s a philosophy that seems right for a man who’s dedicated to living in the moment, to having experiences rather than discussing them—a philosophy directly at odds with art criticism, if not the profession of journalism itself. But whether or not Richman ever sits down to a straightforward interview, the reality is that the answers to our questions have been available all along in the words of his songs. In a 2006 Seattle Times interview, another famous punk icon, Joan Jett, said “If you don’t know who I am from listening to my music, then you’re not going to figure it out from me talking to you, either.” It’s in Richman’s lyrics, not in interviews, that he answers our questions. Chiefly: Who is Jonathan Richman, really? What motivates this spastic man with the pouty lips?

For one answer, look to 2004’s Not So Much to Be Loved as to Love—specifically, to the phrase emblazoned across the CD itself: “He gave us the wine to taste it, not to talk about it!” The song to which the quote refers (“He Gave Us the Wine to Taste It”) is Richman’s reminder that to criticize, or even discuss, the wine is to waste it. And what is wine criticism, if not a stone’s throw from other types of criticism? Say, music criticism?

“Es como el pan,” Richman tells us at the beginning of “El Como el Pan,” one of the best tracks on this year’s release Because Her Beauty Is Raw and Wild (an album Paste Magazine lauded as his best in years). “We don’t want the past, we want the moment…just like bread. It’s gotta be fresh. Even a day old is getting to be too much.” Like the past, he continues, “it’s better if it don’t imprison us.” But then he adds, “It’s better if words don’t imprison us, either.”