Because more than four years have passed since that Valentine’s Day concert at the House of Blues in Las Vegas, I can honestly say I’m no longer mad at the heckler who bellowed over and over again at the supremely confident, serenely composed figure on stage: “Erykah Badu! You a sexy motherfucker!”

At the time, I hadn’t enjoyed being wrenched out of the quasi-meditative state the neo-soul songstress had stirred me into with her crackling delivery (her voice quavered and wavered like an anxious ancient begging the sky for rain) and mystical presence (only after the show did you realize she’d barely moved). But now, with the benefit of hindsight and an even deeper appreciation for Badu’s music and its intoxicating effect, I understand why that guy risked, and eventually received, the ire of many in that sold-out crowd. His barbaric yawp wasn’t intended to announce that he was horny—it was intended to announce that he was alive.

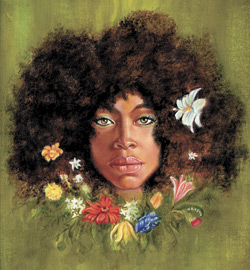

What is it about Erykah Badu—the only shaman ever to have come out of Dallas—that turns grown, apparently sober men into fools loopy with a love for sucking air on this doomed planet? She’s certainly gorgeous. Possessed of a mushroom-bloom of hair and a face whose vectors connect in a catlike mask of eerie luminosity, Badu is a graceful something to behold. Her body is a sleek statue that, on the night I saw her in 2004, she carefully calibrated to move as if in freeze frame, engaging in long, Pinteresque pauses for maximum impact before adjusting position and starting the cycle all over again. It’s called patience.

Indeed, her ability to take her time, to trust enough in herself to allow moments to progress at her pace so that she, not the howling masses, is in control of the work, not only represents the mark of a true artist—a singular voice, free from fear—but also that of a goddamn adult. Could Beyonce produce a song like “Tyrone,” a self-assured reminder—and a prime example of comedy with deadly serious intentions—to bottom-feeding boyfriends that it’s time to “call Tyrone/and tell him come on, help you get your shit”? It’s a far cry from Destiny’s Child’s exhortation for a man to pay those “Bills, Bills, Bills.”

In a musical culture that so often caters to, and is indeed performed by, Tootsie-Pop suckers fried on their own youthful narcissism, Badu’s songs serve as a reminder that most of us don’t have a thing to say until the calendar pages have flipped a few times. Badu has shown this tendency her entire career, from the playful hip-hop-style R&B (i.e., neo-soul) strutting of 1997’s Baduizm on up to this year’s politically-minded New Amerykah Part One (4th World War), which I consider her masterpiece.

While I concede that “Green Eyes,” from 2000’s Mama’s Gun, may be her most sublime and ambitious ode to her predecessors, particularly Billie Holiday, her ’08 maturation shows a willingness to drop anchor in unpredictable waters—without sinking. Her latest unspools in undulating waves of Sly-and-the-Family-Stone funk (as in the Roy Ayers–produced “Amerykahn Promise”), East-Coast cocaine rap (the Shafiq Husayn–produced “The Cell”) and a general tendency toward vertiginous soundscapes unmoored from traditional choruses, though repetition of a type heard on her hit “On & On” (from Baduizm) still reigns.

On “Master Teacher,” for example, Husayn chops up Curtis Mayfield’s “Freddie’s Dead,” elevating the resulting hypothetical refrain—”What if there was no niggas only master teachers?/I stay woke”—to a forward-looking affirmation of the continuous present that simultaneously, and strangely, points to the past. In other words, the antecedent/influence is reborn as Badu, ad infinitum.

Badu’s indebtedness to hip-hop isn’t as overt as Lauryn Hill’s, but it’s just as pronounced. She cleverly expands upon Dead Prez’s maxim “It’s bigger than hip-hop” by declaring “It’s bigger than religion/hip-hop” over Madlib’s finger-snapping yet subdued production on “The Healer.” The referential ante is further upped here when she announces that “this one for Dilla,” the producer—and Madlib collaborator—J Dilla, who died in 2006 from a blood disease.

Indeed, Dilla’s ghost floats throughout the entire 11-song disc, culminating in a final haunting on “Telephone,” which begins with a call from Ol’ Dirty Bastard. Another long-time associate, Ahmir “?uestlove” Thompson, of the Roots, and James Poyser orchestrate the affecting instrumentation. But it’s Badu, and not those in the heavens or on the ground, who ultimately shines. All hail the Queen.