Two days after Thanksgiving 2004, a double-turboprop transport plane began its early-morning taxi toward the runway at Bagram Air Base, a half-hour north of Kabul. Army Spc. Harley Miller was one of two military passengers.

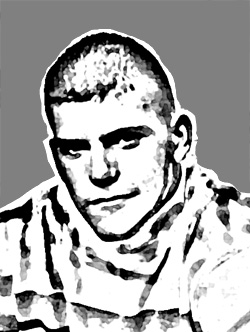

The young, stocky, square-jawed chopper crew chief had just finished a few days of R&R and was headed back to his air cavalry unit 450 miles west in Farah—a front line in the U.S. war with the Taliban. He’d chatted on the phone with his wife in Spokane and e-mailed his mother near Seattle. “Love you bunches,” he wrote.

Farah’s hair-raising gravel runway, like other remote Afghan airstrips, is best maneuvered by short-takeoff-and-landing planes such as the Spanish-made CASA 212. In Afghanistan, the planes are owned and operated by private contractors working for the U.S. government—in this case, Blackwater Worldwide.

Blackwater had just launched its operations in Afghanistan under a two-month-old, $35 million Pentagon contract, part of the Bush administration’s expanded privatization of military services, a shift intended to create what then–Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld called a leaner, lighter war machine. Blackwater’s duties included shuttling military personnel and cargo over the mountainous Afghan topography, where the ground always seemed to be rising. Upon departing Bagram, a contract pilot had to know the terrain and be ready to wing it without radio or radar tracking.

But then, Blackwater’s gung-ho pilots weren’t being paid $600 or more a day because it was easy.

In the cockpit that morning were Capt. Noel English, who formerly flew cargo planes in Alaska, and First Officer Loren “Butch” Hammer, a onetime smoke-jumper pilot in Washington state. Both were in their mid-30s and experienced with the C-212. They had arrived together in Afghanistan only two weeks before and had requested joint assignments. A Blackwater mechanic also rode up front. In addition to their two Army passengers, the three-man crew was transporting 400 pounds of low-explosive illuminating mortar rounds used to light up enemy positions.

Taxiing to Bagram’s Runway 3, English suddenly stopped the plane. “Uh, apparently they got a last-minute passenger for us here,” he told Bagram control. Lt.Col. Michael McMahon, a battlefield commander and one of the highest-ranking U.S. officers in Afghanistan, hopped aboard. He’d been late leaving a command meeting.

As they lifted into the cool, clear Afghan morning, the passengers on the flight, known as Blackwater 61, likely didn’t know they were traveling a route rarely taken over the Hindu Kush mountains—and one never before flown by this crew. But 20 minutes into the trip, as the C-212 banked over the Bamian Valley about 150 miles south of the Uzbekistan border, that inexperience had clearly become a problem. According to a transcript from the cockpit voice recorder—in which expletives were deleted—Blackwater’s pilots were already lost.

Capt. English: I hope I’m goin’ in the right valley.

First Officer Hammer: That one or this one?

English: I’m just gonna go up this one. . . . We’ll just see where this leads.

The pilots suspected it could be a dead end, but continued on, chatting about looping back if they had to. No one sounded worried.

Hammer: Yeah, this is fun!

English: We’re not suppose to be havin’ fun though.

Hammer: Exactly.

English: No fun allowed god-(expletive).

Hammer: It’s supposed to be all work, we can’t enjoy any of it.

English: Exactly.

Hammer: ‘Cause we’re getting paid too much to be havin’ fun.

Blackwater mechanic Mel Rowe, 43, a onetime Army chopper pilot, seemed to be trying to caution them. “I don’t know what we’re gonna see,” he said from his cockpit jump seat. “We don’t normally go this route.”

English: All we want is to avoid seeing rock at twelve o’clock.

Hammer: Yeah, you’re an X-wing [Star]fighter Star Wars man!

English: You’re (expletive) right. [Pause] This is fun!

The fun continued as the plane swung through a canyon. English fiddled with his MP3 player to get appropriate mood music.

English: Philip Glass or somethin’ suitably New Age’y.

Hammer: No, we gotta have butt rock, that’s the only way to go. Quiet Riot, Twisted Sister.

English: I swear to God they wouldn’t pay me if they knew how much fun this was.

But within minutes, the happy chatter turned to urgent pleas. They suddenly realized they were boxed into the canyon and the plane was dangerously low. The pilots began an emergency climb.

English: Come on baby, come on baby, you can make it.

Rowe: Okay, you guys are gonna make this, right?

English: Yeah-h-h, I’m hopin’.

Rowe: Hope we don’t have a downdraft comin’ over that, dude.

[A stall-warning device gives off one beep.]

Rowe: Got a way out?

English: Yeah. [Pause] We—we can do a one-eighty up in here.

Rowe: Yeah, I’d pick one side or the other to . . . ah.

English: Drop a, drop a quarter flaps.

Rowe: Okay, yeah, you’re . . . ah.

Hammer: Yeah, let’s turn around.

English: Yeah, drop a quarter flaps.

Rowe: Yeah, you need to, ah, make a decision.

[Sound of heavy breathing begins.]

English: God (expletive)!

Rowe: Hundred, ninety knots, call off his airspeed for him (unintelligible).

[Stall-warning alarm is now constant.]

English: Ah (expletive, expletive)!

Rowe: Call it off, help him out, call off his airspeed for him (unintelligible), Butch.

Hammer: You got ninety-five. Ninety-five.

English: Oh God!

English: Oh (expletive)!

Rowe: We’re goin’ down.

Unidentified voice: God!

Unidentified voice: God!

When rescuers finally arrived at the wreckage of Blackwater 61, they determined the plane had glanced off a peak and fallen into a snowfield. Bodies and debris were strewn for 500 feet. They also determined that Miller, the Army crew chief, had survived. He’d left a trail around the plane, along with a snuffed-out cigarette and two piss holes in the snow. The two pilots and the mechanic, along with Lt. Col. McMahon, 41, and Army Chief Warrant Officer Travis Grogan, 31, died on impact.

Miller must have been stunned in several ways—he’d hit a mountain, and lived. A wing had detached and the fuselage had come apart as the plane somersaulted in the snow, yet none of the mortar rounds had gone off. Despite cuts, broken ribs, and serious internal bleeding, Miller had crawled in and out of the wreckage, investigators discovered. He eventually settled in near the shattered tail section, and unrolled several sleeping bags. It was freezing, and he had no cold-weather gear, though there was water, military rations, and a signal flare. He lay down and waited. And waited.

Landings were not tracked at the remote airstrip in Farah. No one even missed Blackwater 61 until the afternoon, when a passenger slated for the return flight wondered where the plane was. A search was launched, but it went in the wrong direction at first because officials thought the pilots had taken a more common southerly route.

Miller, 21, lasted into the early evening—as long as 10 hours—investigators estimate. Then he succumbed to his injuries and exposure. The crash site wasn’t found until the next day, and severe weather and turbulence kept rescue teams away for another day. A recovery team found the bodies of six men, pilots all, who’d flown their final mission.

The flight of Blackwater 61 has now taken a new course. Last month, it landed in front of a skeptical congressional committee headed by the aggressive California Democrat, Rep. Henry Waxman. He revealed that the crash is part of a wide-ranging government investigation into Blackwater’s sometimes deadly world adventures. Waxman hinted he might back new legislation to rein in the company’s operations.

Perhaps more ominous for Blackwater and other contractors, the families of Harley Miller and the two other military passengers have filed a federal lawsuit that threatens to make contractors liable in court for their performance and undercut the government’s effort to privatize the war on terror. The suit seeks actual and punitive damages from Blackwater for failing to follow flight planning, safety, and rescue procedures in 61’s crash. No dollar amount is specified.

Blackwater claims the company is immune from lawsuits under a 1950 Supreme Court ruling referred to as the Feres doctrine, which blocks damage claims against the military. That same immunity extends to Blackwater as a contractor for both the Pentagon and State Department, the security firm says. But in a stunning Oct. 5 ruling, a federal appeals-court panel in Atlanta rejected Blackwater’s argument and said the families’ lawsuit can go forward.

“The thing everyone—the court, Waxman’s committee—is really wrestling with is, what are the bounds of responsibility for these private contractors?” says Jacksonville, Fla., attorney Robert Spohrer, who is handling the lawsuit against Florida-based Presidential Airways, a Blackwater subsidiary that operated the C-212. Spohrer thinks the corporation will appeal the ruling to the Supreme Court. If it loses, he says, that could leave other contractors vulnerable, too, causing their liabilities and costs to soar in war zones.

Already, government investigators have concluded that Blackwater was at fault in the Afghan crash and the loss of life was avoidable.

Relying on two crash investigation reports that are public but have received little attention—one by the National Transportation Safety Board and one by a joint U.S. Air Force and Army task force—Waxman’s House Committee on Oversight and Government Reform summed up the reports’ findings thusly: “The crash and the deaths of the crew and passengers were caused by a combination of reckless conduct by the Blackwater pilots and multiple mistakes by Blackwater.” Those mistakes included “hiring unqualified and inexperienced pilots, failure to file flight plans, and failure to have proper equipment for tracking and locating missing aircraft.”

In other words, says Sarah Miller, 23, Harley’s widow and mother of their now 4-year-old son, Korey, “They’re responsible.”

Blackwater CEO Erik Prince and his attorneys disagree with the accident findings and, in court papers, claim the company is not legally responsible for the crash (Blackwater would not comment further to Seattle Weekly). A onetime Navy SEAL and former White House intern for George H.W. Bush, the confident and well-connected (but typically camera-shy) Prince founded Blackwater in 1997, boasting that he was “trying to do for the national security apparatus what FedEx did for the Postal Service.” His company held $200,000 in government contracts in 2000; since then, it has received $1 billion worth of war work, which includes providing security for diplomats. Blackwater is now the largest of 15 private security firms operating in Iraq, where it has earned $830 million the past two years.

At its sprawling Moyock, N.C., compound and elsewhere, Blackwater trains about 40,000 people annually for law-enforcement and military roles worldwide. Employment in its private army, navy, and air force offers pay equal to risk. According to a government study, Blackwater charges U.S. taxpayers $1,222 per day for each of the more than 800 guards it employs in Iraq. That comes to an annual paycheck of $445,000 per guard, “or six times more than the cost of an equivalent U.S. soldier,” the report notes. The Bush/Cheney effort to privatize some military services and tasks, Rep. Waxman noted at his hearing, “is working especially well”—if you’re Blackwater.

Prince made a rare public appearance at the Waxman hearing. (He has since granted a number of network TV interviews and, according to recent news stories, has commanded his PR troops to take no prisoners.) He noted that his soldiers are volunteers in the war effort, and denounced what he called “negative and baseless” allegations about his company. “Most of the attacks we get in Iraq are complex,” he said at the hearing, “meaning it’s not just one bad thing, it’s a host of bad things: a car bomb followed by a small arms attack, RPGs [rocket-propelled grenades] followed by sniper fire.” Blackwater has lost 27 employees in Iraq, and numerous others have been wounded and maimed, Prince said.

A federal study recounts 195 shooting incidents in Iraq involving Blackwater forces since 2005—in most cases, Blackwater’s mercenaries fired first, often from moving vehicles in a motorcade, and were unable to determine who may have been hit. Prince, at the hearing, said that shouldn’t surprise anyone. Blackwater has conducted in excess of 16,000 Iraq missions since 2005: “In that time, did a ricochet hurt or kill an innocent person? That’s entirely possible.” And Iraq is no place to get out and ask who’s been shot, he said.

Nonetheless, Waxman’s oversight committee, along with the Justice Department, is examining a pattern of allegedly reckless shootings involving the company. The inquiry was spurred in part by the Sept. 16 deaths of 17 Iraqi civilians at the hands of Blackwater guards, who were protecting a U.S. diplomatic convoy in Baghdad. The Iraqi government says the shootings were unprovoked, but the Bush administration has backed Blackwater’s claim of self-defense. (Supervision of such convoys has now been shifted to the military.)

More than 120 Blackwater employees have been fired for improper conduct in recent years, including one now-notorious local man. Andrew Moonen, 27, of Seattle, allegedly shot and killed a guard of the Iraqi vice president around 11 p.m. Christmas Eve last year in the Little Venice international zone in Baghdad. He allegedly fired multiple shots, hitting the guard with three rounds from a Glock 9 mm. Initially too drunk to be interviewed, a government report says, Moonen later claimed he shot in self-defense. The FBI recently said it would review the case.

State Department documents show that Moonen, an ex-Army paratrooper who lives in South Park, was fired for violating alcohol and firearms policies, and forfeited $14,700 in various Blackwater payments due him, including a $3,000 Christmas bonus. He was quietly sent home to Seattle. In a memorandum to Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice, the U.S. Embassy reported that the Iraqi government agreed to keep the incident out of the press but felt justice hadn’t been done. “The Embassy,” the memo states, “described Iraqi concerns as follows: ‘Iraqis would not understand how a foreigner could kill an Iraqi and return a free man to his own country.'” Said Waxman of Moonen: “If a drunken U.S. soldier had killed an Iraqi guard, the soldier would face a court martial. But all that has happened to the Blackwater contractor is that he has lost his job.”

Moonen declined to comment. But his Seattle attorney, Stewart Riley, has complained by letter to the Waxman committee about the tone of the hearing. “People are assuming that a murder has been committed by someone who hasn’t even been charged,” Riley said in an interview. “Where is the presumption of innocence?”

Internal e-mails between the State Department and Blackwater, revealed at the hearing, debated how much the family of the dead guard should be compensated. The U.S. chargé d’affairs recommended a $250,000 payment from Blackwater. But that was pared down to $15,000 after the Diplomatic Security Service claimed desperate Iraqis might purposely get themselves killed if large payouts were available to survivors. (The price has fallen even further, it appears: The family of an innocent Iraqi killed by Blackwater this year was given just $5,000).

The Iraqi parliament is weighing changes that could lead to future prosecutions of U.S. contractors. But as it stands, contract workers such as Moonen are immune from Iraqi law and can’t be tried in military courts. As for applicable U.S. laws, “My understanding,” says attorney Riley, “is that [the Justice Department] has not arrived at a decision on that.”

Such shooting incidents, as well as the crash of Blackwater 61 and the ambush deaths of four Blackwater employees in 2004 (leading to the infamous hanging of their burned bodies from a bridge in Fallujah), ought to have the U.S. thinking twice about privatizing its wars, Waxman says. He recently promised Sarah Miller and others that “Blackwater will be [held] accountable.”

But the families of the soldiers are holding their own hearings, of sorts. “When this [crash] happened, I didn’t even know what Blackwater did, who it was—I honestly didn’t,” says Sarah Miller. “I had talked [a day] earlier with Harley, and he said he was going to another city, but I didn’t even know he was taking a plane.” Miller and her child are joined in the suit by Harley’s mother, Christine Miller of Everett, and by military widows Tracy Grogan (along with her two children) and Jeanette McMahon (with her three children).

“At first, I didn’t want to take part in the lawsuit,” says Miller. “I didn’t want to deal with it, to go over Harley’s death again. It’s a horrible thing. Then I thought about other wives who might have to go through it if I did nothing. And that my husband loved the military and he would have fought to find the truth.”

A week after the crash, services for all six men were held in Afghanistan, followed by burials in the U.S. One of Mike McMahon’s executive officers remembered him as a strapping chopper pilot and “the man who championed the cause of the underdog or the less fortunate.” Travis Grogan, an Oklahoman partial to Stetsons and Hawaiian shirts, was fondly recalled by a friend as someone who could sleep “for 18 hours in 100-degree heat in a crowded tent 500 feet from a runway.”

Harley Miller grew up with three older sisters in Idaho and Spokane. In a written remembrance, his mother recalled that his final e-mail spoke of his love for wife Sarah and “his other love”: “the love of the men he served with.” At his request, she’d prepared a huge holiday meal for his buddies in Afghanistan, including chicken, ham, mashed potatoes, and pumpkin pie. “The first boxes,” she wrote, “were arriving the week of Harley’s passing.”

At the Afghanistan services, a Blackwater official also spoke about the loss of his pilots and mechanic, and their dedication to the U.S. effort. “To have such noble efforts marred by the deaths of these fine men is a tragedy beyond my words to express.”

In mid-November 2004, Blackwater was literally just getting its operations off the ground. As a result, according to copies of internal Blackwater documents, the company knowingly hired inexperienced personnel for its operations. Sixteen days before 61’s crash, the company’s Afghan site manager wrote to another top Blackwater official: “By necessity the initial group hired to support the Afghanistan operation did not meet the criteria identified in e-mail traffic and had some background and experience shortfalls overlooked in favor of getting the requisite number of personnel on board to start up the contract.”

Both pilots had good records when earlier flying the stubby C-212s—English for a private cargo firm in Anchorage and Hammer for the U.S. Forest Service, guiding C-212 smoke-jumper planes and DC-7 air tankers over Eastern Washington. But investigators concluded that English and Hammer “were behaving unprofessionally” and were “deliberately flying the nonstandard route low through the valley for ‘fun'” on Nov. 27, 2004. Weather and enemy fire were not factors when Blackwater 61 slammed into a 16,500-foot peak around the 14,600-foot level, but poor decision making was: Probers said there was no evidence the pilots used their oxygen in the unpressurized 212. Without oxygen, above 10,000 feet, pilots can become disoriented (use is mandatory at 12,000 feet).

The families of English and Hammer couldn’t be reached for this story. But last week, Vern Arledge, chaplain for the Redmond Fire Department in Oregon, who officiated at Hammer’s memorial at the local airport, recalled Butch as “a very dedicated person, a very dedicated pilot.” Hammer’s father ran the FAA facility in Redmond, and Butch fueled airplanes as a teenager. “He loved flying,” said Arledge, “and he was very qualified.” Even so, accident investigators say, Blackwater should not have paired two newcomers to the Afghan theater.

Investigators also cited several regulatory violations, including stopping on the taxiway to pick up a passenger. If the crew had followed the rules, Lt. Col. McMahon would not have been allowed to board that day. As head of the U.S. military’s Task Force Saber units of western Afghanistan, he was, until this year, the highest-ranking officer killed in Afghanistan. (In May 2007, Army Col. James Harrison was shot by a deranged Afghan soldier.)

When McMahon’s widow, Jeanette—an Army colonel and also a chopper pilot—appeared at the oversight committee hearing last month, she cuttingly suggested the wrong person died that day in the Hindu Kush. Referring to the Blackwater founder sitting in the audience, she said her husband, “like Mr. Prince, was a CEO of sorts in the military, as an aviation commander, and as such had amassed a great safety record in his unit. It is ironic and unfortunate that he had to be a passenger on this plane, versus one of the people responsible for its safe operation.”

Harley Miller’s widow opted not to attend the D.C. hearing. She has difficulty discussing her husband’s death with strangers. The two were friends since junior high and married in 2003, the year after he graduated from high school and enlisted. “It sounded like he was very disoriented,” Sarah Miller says about his miraculous, if brief, survival. “He couldn’t think straight—maybe he knew he wasn’t going to last, I don’t know. If they’d just gotten there in time….”

Blackwater was not penalized by the government for the crash, and no contracting changes were made to improve safety, the oversight committee found. In September, the Defense Department awarded a new, $92 million contract to the company. It guarantees Blackwater’s services in Afghanistan for at least five more years.