Forget Green Lake. I wanted to walk around Lake Washington. Why? Of course it was hard to explain.

“To reflect on our urban relationships with the lake” was sort of true, but it sounded like grad-school mumbo-speak, and I happily fled grad school a quarter-century ago, a long way from earning any degree. I wanted to gather evidence that the increasing wealth necklacing the lake is choking it for the rest of us, but hesitated to say this. Communism is a hard sell in Kirkland.

Eventually I realized the best explanation was the simplest and most honest one: I like the lake, and I like to walk. And I wanted to see what would happen.

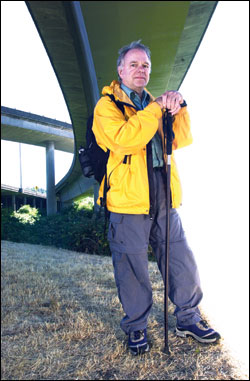

MY WIFE, PATTY, deposits me under the I-90 bridge in Bellevue on her way to work. There’s a park here, Enatai Beach. It has a counterpart where I-90 launches itself off Seattle, Day Street Park. These are bizarre, contradictory environments: softly sculpted arcs of manicured grass contravened by virtuosic feats of concrete engineering thrusting overhead and the endless rumble, swish, and shriek of freeway traffic. They’re uneasy places to spend time. They trigger an instinctive flee-or-duck reaction in the human brain, not very different from when a marmot unhappily finds itself wrapped in a hawk’s shadow. But the alternativeleaving these under-freeway wedges as weed-infested wastelandswould be worse.

I have a bias about land use around the lake, and I might as well lay it out now: There’s not nearly enough for the public. Roughly 76 percent of the lakeshore is locked up as private homes, private clubs, and private marinas and for other restricted uses. The shore of Lake Washington could have been an entirely public treasure, like Oregon’s seacoast, where all 362 miles of beach and headland have been preserved for everyone’s use.

Why wasn’t it? The Olmsted brothers tried, and thanks in great part to their visionary master plan for the Seattle park system, Seattle gives the people more than twice as much shore as all the suburbs combinedabout 11 miles, not counting the University of Washington’s shoreline. Mark Hinshaw, former chief urban designer for Bellevue, tells me the attitude toward public space in the burbs was different, at least back when waterfront property might have been available. “Suburbs have seemed to be based on notions of exclusivity and private space,” he says. “I’m not sure that was ever a public policy, but it was a private attitude.”

I’m packing some contrarian reading on my trek: Thoreau’s Walking, a slim book published posthumously in 1862. Thoreau suspected an American future where most of our land would be locked up behind fences and “No Trespassing” signs, and the thought made him apoplecticyou can sense his blood approaching boil as the sentences tumble forward:

At present, in this vicinity, the best part of the land is not private property; the landscape is not owned, and the walker enjoys comparative freedom. But possibly the day will come when it will be partitioned off into so-called pleasure-grounds . . . when fences shall be multiplied, and man-traps and other engines invented to confine men to the public road, and walking over the surface of God’s earth shall be construed to mean trespassing on some gentleman’s ground. To enjoy a thing exclusively is commonly to exclude yourself from the true enjoyment of it. Let us improve our opportunities, then, before the evil days come.

I pick my way north under I-90 along a 12-foot-wide corridor enforced by chain-link fences on each side. These, in concert with the freeway ramps slashing overhead, would for Thoreau constitute Evil Days indeed. My expedition is just beginning, though, and it would be a shame to let cranky Henry sour the project within the first couple of miles. Anyway, the freeway roar begins to ebb as I plod into the slough, the avian commotion increases, and my mood brightens.

Mercer Slough is one of the urban area’s least plausible environmental triumphs. As the Army Corps of Engineers dredged the Lake Washington Ship Canal, they drained 9 feet of water out of Lake Washington in 1916, exposing assorted peat bogs for imaginative uses. Union Bay and Columbia City wetlands became landfills; Mercer Slough for a while tolerated farming. When an oddball named Siegfried Semrau became Bellevue’s parks director in 1962the incorporated town was then only nine years oldhe hatched the radical-for-its-time idea of leaving it alone as an urban nature preserve. Despite a consulting biologist’s 1970 report that called it “unattractive, unfishable and unproductive,” by 1989 the city had pieced together about 320 acres, fulfilling Semrau’s vision.

It’s frightening how fast our perception and understanding of environmental issues can change: One generation’s wasteland becomes the next’s treasure, or vice versa. We now know that the dense wetland vegetation filters sediment from river water and urban runoff en route to Lake Washington and provides habitat that’s hardly “unproductive” for great blue herons and muskrats.

And mosquitoes. I duck into a small clearing to pee and suffer my first wildlife attack of the trek. Hey, we’ve saved your home from development, and this is our reward?

It isn’t easy to walk the lakefront through Bellevue. I wind through the upper- middle-class neighborhoods west of Bellevue Way looking for unadvertised trails and pocket beaches. There are some, but they’re tough to negotiate without a local escort. I have the uneasy feeling of being an interloper, even when I’m staying on public streets. In one cul-de-sac, a pair of golden retrievers growl a command to retreat. On another placid street, I see a warning tacked to a tree: “Mailbox Is Under Video Surveillance.” I’m relieved when I get to Chism Beach Park, except I remember coming to this park once before, six or seven years ago, and a city employee ordered me not to sit on the boulders bordering the beach. What, my buns might scratch the municipal rocks?

ALL THE PARKS HAVE rules, but I discover that their density and the way they’re expressed bear directly on my mood. In Kirkland, Waverly Beach Park posts “A Friendly Reminder” to keep dogs on leash. I’d do it, cheerfully, if I’d brought a dog. Renton, though, posts its full constellation of 30 park rules, spelling out in lawyerly detail how I may not fire up a portable barbecue “over 36 inches in length” or tote a sword (!) into the park.

Chism Beach is all but deserted; there’s exactly me and two women. We start to talk. They wonder what I’m doing scribbling in a notebook. “You look too professional to just be wandering around the beach,” one says. I tell the truth, that I’m hiking around Lake Washington, aware that it sounds about as professionaland as saneas looking for stray meteorites. But they both exclaim “Cool!” and actually seem envious. They say they wish they could do it. I suggest they do.

Our beach talk turns to Bellevue. “I’ve been all over the world,” says one of the women, “and I haven’t seen any place I like better.” I ask her why. She doesn’t hesitate a second: “Because it’s well kept.”

It is that. Bellevue’s parks seem manicured, more carefully tended than those of the other municipalities bordering the lake. Houses are painted, lawns watered and mowed, downtown so pristine it looks like it’s vacuumed and squeegeed daily. There are pockets of urban grit, but a resident never has to see them if she doesn’t care to. I plod north from Chism Beach, wondering why a city correctly described as “well kept” makes me feel vaguely uncomfortable. Squalor isn’t an alternativeI’ve been in slums in Mexico and Moscow, and squeaky-clean is clearly better.

I recall a conversation with Philip Langdon, one of the country’s most articulate urban-design critics. “It’s a dangerous world, and people are fragile,” he said. “I think we crave harmony and coherence in our environment because it establishes that there’s some safety where we live. At the same time, I think it’s wrong to say that we want only harmony.”

On through Medina, where I notice no one else walking with a backpackin fact, almost no one else on foot at all. I figure that if the police are to take an interest in me anywhere, it will be in Medina, and I sort of want to make it happenpart of the experiment. I plod back and forth in front of the cop shop, conveniently located at the town’s lone beach park, but the law doesn’t stir.

Midafternoon through this first day, in fact, I’m astonished by the solitude of my urban adventure. It’s late June and the weather’s inviting enoughmid-60s, light overcast, no rain expectedbut the Eastside parks, sidewalks, and trails are all but deserted. I’ve had more company in the Cascades. On a Saturday hike to Snow Lake, I once counted 197 other hikers in three miles, an encounter every 80 feet on average. Today I’ve seen an actual pedestrian, not counting yard workers and people ambling to their cars, maybe every half-mile. Maybe it’s the allure of the mountains, maybe the compulsion to cram in more efficient exercise at the gym. Maybe nobody has realized that we’re allowed to walk around the lake.

I plod into Kirkland and an appointment at a B&B a few blocks off the lake at 4:30 p.m. My pedometer reads 17.7 miles. I’ve never walked this far in a day, never had a reason to. I’ve had a craving for junk food for the past couple of hours, which is one of the hazards of urban hiking. What fool would grope for gorp when there’s a Kidd Valley right across the street? But I settle for a root beer float and a date with my wife later at Szmania’s. Pan-roasted halibut with sweet onions, then a triple-turbo-chocolate-mocha assault for dessert. Look, the point of an urban hike is not sensory deprivation, but exactly its opposite.

“I STARTED HERE 19 years ago,” says Neal Christensen, sales manager at Hallmark Realty in downtown Kirkland. “You could buy a waterfront house for $150,000. Now, one just went for $1.2 millionan 800-square-foot bungalow.”

Christensen prints out a sheaf of multiple listing reports on waterfront properties. I’m surprised: There are several one-bedroom condos in the $250,000 range, most of them in those ’60s complexes built like sheds on piers. No other prospects appear to be of relevance to, say, a mildly successful writer. I see a modest 3BR, 1.75BA, 2090SF in Renton for $2.3 million and a rather more imposing 7100SF in Hunts Point for $8.45 million. Christensen tells me that the recession hit the $400,000-$800,000 market hardest; prices are down, though he couldn’t say how much. Higher up, he says, the buyer demographics have shifted. “It used to be techies; now it’s older money.”

Whether it’s new or old money, it’s not squeezing into those 800-square-foot bungalowsit’s tearing them down and building megahouses. “Progress is progress,” says Christensen. “It doesn’t make economic sense to have a bungalow on those lots anymore.”

Tere Gidlof lives in one of those 800-square-foot bungalows, and she has to agree. “He’s rightand it’s really sad,” she tells me. “I’ve lived in this house for 33 years now, and it’s gone from the place I thought I would die in to a place I don’t see how I can afford to keep much longer. And I’m not retired.”

Gidlof chairs the Kirkland Alliance of Neighborhoods, and she says teardowns, view blockers, and crushing property taxes have become a chronic issue in three once ordinary Kirkland neighborhoods. She describes the growing clash of cultures: “Some people are talking about how to bury the wires, while others are trying to figure out how to stay in their homes.”

Kirkland has made an earnest effort to lay out a “public pathway” that weaves among several of the big condo buildings and the lake, but it’s more novelty than useful trail. I found I liked the idea of sauntering between the affluent and their lake view more than the reality. One condo for sale offers “No public paths” as a selling point, hinting at how some residents feel about it.

The northeast lakeshore has plenty of parks, and I walk through all of them. Juanita Bay serves up a glimpse of a redwing blackbird, an exclamation point flashing in the air. A row of defunct pilings off the north boardwalk functions as a great blue heron airport; jumbo birds arrive and depart every few minutes. A few ghosts of the golf course that existed here until 1975 persist, such as weeping willows, but nature has reclaimed much of the artificial landscape.

I’m no landscape anarchist; I appreciate a garden skillfully orchestrated with color and the cool green carpet of a well-tended park (as long as I don’t have to do the work). But there’s a price for reshaping landscape for human recreation or aesthetic pleasure. We usually think of landscape architecture as a way to impose order on chaos, but it’s really the oppositelandscaping introduces chaos. Why else would nature keep pushing to repair to its own equilibrium?

St. Edward State Park is another jewel, and the public a beneficiary of another land use that went obsoletea seminary closed here in 1977, and a 316-acre state park materialized a year later. I come here often, more to lose myself in the South Canyon than to visit the lake. It’s a 200-foot-deep geological yawn with groves of big-leaf maple 60 to 80 feet high that practically form a canopy over the canyon. Never mind the clich黠this is a green cathedral.

And a legitimate wilderness experience. Naturalist John Tallmadge wrote in Audubon magazine that to appreciate nature enclosed within a city, we only need to adjust our perspective of scale and “regain that beginner’s mind before which the world still appears fresh and luminous and unbounded”in other words, see and think like a kid again. It works, and more crucially, it’s essential. In the last century, civilization has eclipsed and usurped nature so rapaciously that our best shot at saving her probably starts in the enclosed and protected vestiges like this park.

And anyway, a round-the-lake hiker needs this refuge from the nastiest leg of the circuit: five miles of Juanita Drive with no sidewalk, only the asphalt shoulder. The traffic noise is tense and abrasive. I’m unwelcome here, a skater in a buffalo herd. I pick up the Burke-Gilman Trail at Bothell Way, gratefully, and plod toward my drop for the night, a friendly Lake City church where Patty joins me to sleep on a fold-out couch in the library. Second day: 15.3 miles.

I BREAK AT A park bench near 145th Street and the Burke-Gilman Trail. The bench faces a private beach garden and the lake, but you’d have to build bleachers to enjoy the viewsomeone has woven plastic inserts through the chain-link fence between the trail and the beach.

A pear-shaped man rattles by on a creaky one-speed bike. “Must have been a nice little rest stop before some asshole put up that fence,” he growls.

In fact, the B-G resembles a green tunnel in its two miles through Lake Forest Park, a concrete wall on its west side and a fence toward the lake. Bud Parker, who managed the trail construction for King County in the 1970s, tells me it was the product of a series of “very heated meetings” with lakeshore home owners. “The fence became the pivotal point that got them tonot like it, but at least accept it.”

Peter Lagerwey, Pedestrian/Bike Program coordinator for the city of Seattle, says that homeowners invariably howl at the proposal of an adjacent trail. “They say people are going to throw trash in my yard, run off with my TV,” he says. “But I’ve been here 18 years, and I can’t recall a single complaint from a homeowner after a trail was built. Their fears just don’t materialize.”

In Walking, my transcendentalist companion grudgingly admits to the occasional appreciation of “the beauty and the glory of architecture.” I appreciate it more than occasionallyI’ve written far more about architecture than nature, and I can recognize a lot more architectural styles than tree species. And sure, I’ll take a house on the lakeif I ever become Stephen King (unlikely) or Deepak Chopra (even less). Mine would be on the Seattle side.

All generalizations are suspect (including that one), but on this hike and on earlier kayak expeditions around the lake, I’ve pegged the differences between the domestic architecture on the Seattle and Eastside shores. Those on the Eastside are newer, of course, but also more likely to be dressed for some kind of historic costume party. Mediterranean (Motel) Revival seems especially popular (Kirklanders are currently deriding one sprawling new lakeside manor as “Ramada Inn West”). The Eastside houses are bigger and more pretentious; Seattle houses smaller and more restrained.

An obvious reason is the bigger suburban lots, but the houses also reflect the differences between the old and new facets of the Seattle city-state. The old one dictated that money be spent quietly and deliberately, whether on oneself or on the community weal. The new one shakes and splatters wealth around like a dog emerging from a swim. Paul Allen’s EMP is its centerpiece and symbol, as exhibitionist as it is undisciplined.

Or maybe it’s just that ostentation wears better when it’s a couple of generations old. I spot neo-Tudor and mock-medieval mansions in Laurelhurst and Madrona that are, in a cold objective light, as silly as anything in Bellevue and Kirkland, but they’ve matured into cultural artifacts. It’s as F. Scott Fitzgerald wrote: “Gatsby turned out all right at the end.”

THE ONE CONSTANT in all the neighborhoods ringing Lake Washington is their lack of eccentricityor humor or provocation. I spotted one house in Renton where somebody had built a gag birdhouse 8 feet tall, but that was it. Public art in the parks is likewise safe and predictable. The single exception is John T. Young’s garden of submarine finsThe Fin Project: From Swords Into Plowsharesin Magnuson Park.

Why the compulsion to live on a beachor on a riverfront or in a houseboat or sailboat? It seems like a nearly universal, atavistic urge, a drive to claim two environments at once, to revert to amphibian life. Ask people who live by the lake and they almost always talk about the “soothing” nature of the waterscape, but it goes deeper than that. “There may be some thing in my genetic makeup that makes me want to live on the water,” says Doug Lee, an oncologist who lived on a Lake Union houseboat for three years, then moved to a Lake Washington address on the west shore. “My heritage is Cantonese, and seafaring folk have lived there for generations.”

I ask Lee if there are disadvantages to lakeshore living. “Oh, yeah!” he laughs. “The mortgage payments and taxes are horrendous. You have a dock to maintain, and if you ever want to do anything to it, you have to get a permit. Every two or three years, you have to replace the soil on your lawn because it washes away.” On balance? “I love it.”

A lakeshore homeowner who wanted to stay nameless told me how a heating-oil leak turned into a nine-month nightmare of repair, cleanup, and paperwork when his sump pump flushed the oil into the lake. Obvious question: How healthy can our big urban lake be with a collar of homes, and for that matter, landscaped parks, tight around it?

I call Jonathan Frodge, a King County limnologist who’s been recommended as a straight-talking scientist. “Out in the middle of Lake Washington,” he says, “the water quality is probably better than the drinking water in a lot of metropolitan areas. A lot of the stuff we wash into the lake washes out pretty quickly.”

The problems, he says, attend the shorelines. Lawns that slope into the lake spill pesticides and fertilizers into it, which can’t be healthy for the lake’s inhabitants. Build a bulkhead, and you create an artificial environment that favors predators over Chinook fry, among other things. Still, for an urban lake that we’ve messed with and used so intensely, Frodge says it’s in “great shape.” And the price of keeping it that way, he adds, is “eternal vigilance for everybody.”

Cheers for the lake; now what about me? At the end of Day Three, I check into a hotel near U-Dub after 46 miles in three days. My feet, legs, heart, and lungs are fine; I could walk another half-dozen miles today if these were all that mattered. But the spasming muscles in my lower back and butt feel like washrags being wrung dry by the Hulk; like half the middle-aged human race, I have chronic lower-back trouble. But it’s worse when I’m not walking.

IT RAINS.

A gossamer drizzle greets my fourth day, barely more wet than fog. Then an insistent patter. Then a drencher, accompanied by growls of thunder. I trespass into a shed in a homeowner’s yard and wait. But the rain doesn’t relent, sowhat the hell, I’d rather be walking. I once talked with a bookstore owner in Forks who claimed, more than a little contemptuously, that “people in Seattle are a little afraid of the rain.” The words still sting, but it’s true: The streets and beaches are deserted; we’re hardly the neoprene-skinned land seals we claim to be.

I join a lifeguard training class at Madison Park. I mean “join” in the brotherly sensethey’re wet and cold, and so am I. I watch from the beach as they gamely practice assessing and reviving drowning victims, one rescuer in a rowboat and the other in the water. It reminds me that the lake is deceptive in its picturesque serenity, as is most of nature.

Three years ago, I oversaw the near-death of a friend in Lake Washington.

He was a 50-year-old lawyer, a confessed incompetent in the full spectrum of outdoor sports, but he craved a try at sea kayaking. We took my boats to the placid launch at Mercer Slough, where I spent 15 minutes rehearsing him in forward strokes, controlling the boat, and the wet exit”very unlikely you’ll need it,” I assured him.

After an hour on the lake he was paddling reasonably well, and I did something stupid: I wanted to demonstrate how fast a kayak could move6 knots or so in a sprint. It triggered a squirt of his competitive testosterone, and he tried to keep up. The wind grabbed his poorly controlled paddle, whipped it under the boat, and inverted him. I waited for him to wet exit and pop up, but he didn’t. I had 30 yards to cover, too far to help before he drowned. But he wrenched free enough to grab a mouthful of half air, half water, then finally burst out of the boat as I got there.

By then he was too panicked even to try the re-entry we’d rehearsed in theory. I told him to climb halfway onto my aft deck and I’d paddle him to shore. But with his drag and a headwind, I couldn’t make much progress. I blew my emergency whistle, and a boater at the nearest marina sped out to rescue him.

The sun emerges, grudgingly, in late afternoon. A chilling June wind skips off the lake. The water temperature is in the low 60s; the official swim season opens next weekend. Two people have drowned in Lake Washington so far this year. I bunk down at a friend’s house near Seward Park after 15.8 more miles.

I’VE INVITED A FRIEND to meet me at Seward Park for the last leg of the expedition. He brings a friend, too, a bright and energetic woman who has a secret passion for writing, thinking we will have plenty to talk about.

We do. In fact, I find both of them such good company that I barely take note of the lake and the neighborhoods we breeze through. It seems like a reasonable diversion and rewardI’ve already passed four days meditating on the lake and its neighborhoods mostly in solitude.

But our best walker-essayists have usually traveled alone: Thoreau, Muir, Audubon, Edward Abbey, even Harvey Manning. The curmudgeon of Cougar Mountain told me that he preferred not only to hike alone, but also to flout the fundamental rule of telling someone where you’re going.

“So if something happened, you’d just die out there?”

“Yes, as God intended of us.”

Walking alone, in wilderness or city, is uniquely clarifying. One mind makes all the decisions, editing the environmental inputs so as to meditate fiercely on just one thing or struggle to assemble the Big Picture. The solo walker solely decides where to go, what to see and do and listen to, and what, if anything, it all means.

AND HERE IS what might occur to you as you walk around Lake Washington (which, by the way, becomes a hike of 75.9 miles if you weave and bob capriciously, as I did):

Nobody you meet thinks you’re a doofus for doing it. Most, in fact, seem openly envious. They’d do it themselves, only they don’t have enough time off, or they don’t know how they’d explain it to their families.

Nothing bad happens to youyou aren’t robbed, run over, chewed up, panhandled, or questioned by police. This speaks well of the Emerald City and its suburbs, contradicting the conventional wisdom that abrasive California emigr鳠are grinding away at our legendary amiability. Novelist Jonathan Franzen, who calls himself a “recreational walker,” writes that in recent years, walking in places such as suburban St. Louis and Denver, “a not negligible percentage of the men speeding by me in their cars or sport-utility vehicles feel moved to yell obscenities at me.” But not here.

To your surprise, you shed first your resentment and finally your envy of all the lakeshore homeowners, who initially seemed either more industrious, smarter, or mostly just luckier than you. In four or five days of urban hiking, you’ve gained secret knowledge of the lake in more forms than they’ll ever know from their private decks. And if you want to own Lake Washington all by yourself, all 22,000 acres of it, why’s your kayak lounging on its rack in the garage, dummy?

You’re still a populist at heart, and you still think there ought to be more lakeshore parks and fewer rules. And that more of those parks ought to resemble Seward or Mercer Slough, with substantial vestiges of old-growth forest or working wetlands. At the same time, you’re not unhappy that the goose-extermination program appears to have been working, and that your sneakers (and likely the lake) are cleaner because of it. Yes, you’re inconsistent and hypocritical.

In Walking, Thoreau wrote that almost all man’s improvements “simply deform the landscape, and make it more and more tame and cheap.” I imagine he rode miserably in my backpack, since I generally like cities and think that the intersections of civilization and nature, such as the edges of Lake Washington, are the most intriguing places in the world because they expose us at our most arrogant, careless worstand at our muddling, haphazard best, trying to do the right thing.

Lawrence W. Cheek is an Issaquah-based writer who has written for Seattle Weekly and was a regular contributor to Eastsideweek. He is the author of several books and travel guides.