JIM BITEMAN recalls that he was an eighth-grader at St. Paul’s parish school in South Seattle when Father Patrick O’Donnell pulled him out of class and brought him down to the church’s basement cafeteria to ask a few questions. According to Biteman, the young priest said he was conducting research for his psychology studies at the University of Washington—research that would be ruined if Biteman disclosed the conversation to classmates, who also were to be questioned.

Biteman says he faced a bank of windows while the priest sat behind him and proceeded to ask questions. O’Donnell asked him to picture himself naked in a mirror, then touching himself, then touching another boy in class. “This would go on for about 15 minutes,” Biteman says. In one of the two or three such sessions he had with O’Donnell, Biteman says, he happened to look back and see that the priest’s legs were apart, his hand between them.

What the priest was doing seems obvious now to Biteman, but at the time, he says, he was an innocent who went to Mass every Sunday, who had attended Catholic school since the first grade. Today, Biteman, 39, a Boeing facilities manager and the parent of a son, is among 10 plaintiffs suing O’Donnell for alleged sexual abuse years ago.

Back then, who would have guessed that a man with authoritative credentials—not only was O’Donnell a priest, but one pursuing a doctorate at the state’s top university—would invoke “research” for the purpose of exploiting young boys? Surely not the parents who signed their children up for another research project of O’Donnell’s that was the basis of his dissertation. The topic: encouraging trust between children and adults.

The 1978 dissertation can still be found on the shelves of UW’s Allen library, outlining how O’Donnell used the classic “Prisoner’s Dilemma Game,” in which supposed partners in crime each decide whether to cooperate with police and rat out the other, as a way of measuring trust. Now that O’Donnell’s history is the subject of the lawsuit and a church scandal in his hometown of Spokane, as well as an investigation by the state Board of Psychological Examiners, it is eerie to look at a consent form appended to the dissertation asking for the participation of students and parents on a Thursday, May 18, at St. Paul’s.

O’Donnell did become a psychologist, and since the mid-1980s, he has been practicing in Bellevue—a fact that raises doubt about the psychological profession’s ability to monitor itself as well as highlighting again the Catholic Church’s now-well-known lapses in dealing with priest misconduct. Despite the recent tidal wave of sex-abuse allegations nationwide, this case astonishes. Neither Richard Sipe, a former priest and prominent Catholic reformer who has consulted on more than 100 cases, nor St. Paul, Minn., attorney Jeff Anderson, who has handled about 700 lawsuits against Catholic clergy, knows of another allegedly predatory priest who went on to become a psychologist. “I was kind of shocked by this guy—that he would go from one position where he had the chance to abuse to another,” says Sipe, a psychotherapist.

How could it happen? Did O’Donnell use his psychological training and practice to further an alleged pursuit of boys? As troubling as are Biteman’s recollections and O’Donnell’s thesis, so far there is no evidence that he ever abused a patient. Last month, however, as allegations about O’Donnell were coming to light in Spokane, the state Board of Psychological Examiners received a new complaint. The board won’t release details because it is under investigation—not even whether the alleged infraction occurred while O’Donnell was acting as a priest or a psychologist. Charged with ensuring the moral and professional suitability of psychologists, the board is also investigating a host of allegations about O’Donnell’s pre- practice background that were recently brought to light by a series of articles in the Spokane Spokesman-Review. The lawsuit, meanwhile, filed last month in Spokane County Superior Court, alleges O’Donnell was a “predatory pedophile.”

OTHER THAN THE recent complaint to the state, the picture of O’Donnell’s psychology practice at this point reveals nothing amiss, although the picture is far from complete. Through his Cascade Behavioral Medicine Clinic, he has treated dozens of people experiencing pain and emotional distress after car accidents, according to documents in the King County Recorder’s Office that seem to have been filed in relation to insurance settlements or litigation. One of the people O’Donnell treated, an Edmonds woman, remembers him as “very professional” and “kindly,” a therapist who empathized with her suffering by telling her about a car accident he had been through. He kept a fridge full of complimentary juice and water in his homey office.

In keeping with this area of practice, O’Donnell is listed as a member of an interdisciplinary organization called the American Academy of Pain Management. He has treated, too, clients who were injured on the job and who were receiving worker’s compensation from the state Department of Labor and Industries. Over a period of 10 years, he billed the department for $380,000, some bills coming in as recently as May. He also has treated women who were sexually harassed, according to county documents, as well as a boy who fell from playground equipment at an elementary school.

More is known of O’Donnell’s behavior at the beginning of his psychological career, while he still served as a priest. This bizarre part of the O’Donnell saga begins when the former Boy Scout camp counselor and Army Medical Service Corps officer moved across the mountains to Seattle in 1976.

Jim Biteman remembers O’Donnell being introduced at St. Paul’s as “just one of the parish priests.” He was anything but. According to Father Steven Dublinski, vicar general of the Spokane diocese, the 34-year-old priest was in Seattle for the sole purpose of undergoing therapeutic treatment for sexual misconduct. Dublinski says the diocese knew of two such instances at that point, both at Spokane’s Assumption of the Blessed Virgin parish. Ironically, the head priest for part of O’Donnell’s tenure there was William Skylstad, Spokane’s current bishop, who’s looked to as a national leader in reform of church policy on sexual abuse.

On one occasion, the church now maintains, O’Donnell engaged in sponge bathing with boys during a gym class at the junior high school that adjoined the church. On the other, “a clear case of abuse” occurred, according to the vicar general, who would not elaborate.

THE LAWSUIT FILED last month alleges many more instances of abuse, beginning a year after O’Donnell became a priest in 1971, at Assumption as well as at two parishes he served previously. By the time he came to Seattle, according to the suit, O’Donnell had molested more than eight boys, some of whom he took on outings to Lake Coeur d’Alene in Idaho, where he kept a boat and cabin. So far, the suit doesn’t specify what kind of abuse occurred. But it does charge that O’Donnell procured boys for a friend, prominent Spokane businessman George Robey, who later killed himself. One boy abused by O’Donnell also eventually committed suicide, according to the suit; newspaper reports have linked a second suicide with his alleged abuse.

O’Donnell, whose office phone number has been disconnected and whose sprawling Yarrow Point home on the Eastside was shuttered on a recent visit, has been unavailable for comment and has made only an elliptical statement through his attorney, John Bergmann. Without admitting wrongdoing, Bergmann says his client, now 60, expressed “remorse for any harm he may have caused because of any conduct he may have engaged in.” The Spokane diocese, saying it wanted to counter a tendency to demonize the abuser, disclosed that O’Donnell himself was the victim of abuse as a child in the Boy Scouts.

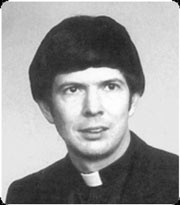

If O’Donnell was as widespread an abuser as the suit claims, it’s unclear if the church knew about it; the suit claims the church did—at the highest levels. But even Spokane Vicar General Dublinski concedes it odd, to say the least, that during a period of time when O’Donnell was undergoing treatment for some level of sexual transgression, he was given access to a Seattle parish with a school. The Seattle Archdiocese made him an associate pastor there—O’Donnell is pictured in a 1978 jubilee edition of St. Paul’s yearbook. O’Donnell’s head priest at St. Paul’s was Father Gerald Lovett, who has spent the past two decades in charge of Redmond’s St. Jude parish. Lovett says O’Donnell’s alleged background as a pedophile is “absolutely new to me.” He remembers only that the young priest was “very popular with the younger people” and a “very good homilist” who talked at a level children could understand.

As O’Donnell was becoming integrated into life at St. Paul’s, his so-far-unnamed therapist suggested that the priest go to school, according to Dublinski of the Spokane diocese, who could provide no elaboration. So O’Donnell began training to become a psychologist—a course of study that culminated in his dissertation on encouraging trust in children.

“That’s remarkable,” says Timothy Kosnoff, the plaintiffs’ attorney. “I’ve never known a pedophile to go that length—getting a Ph.D. to get kids to trust you. It’s almost as if he was applying a scientific method.” Psychologist Bruce Hillowe, who teaches the law and ethics of his profession at the Long Island Jewish Medical Center, doesn’t jump to conclusions. But he does say, “A person with such training in addition to a history of pedophilia could be particularly dangerous.”

Even if O’Donnell hadn’t looked to that particular topic for his dissertation, he would have studied ways of fostering trust, as psychologists generally do, Hillowe says. “Transference” is one phenomenon he would likely have been exposed to, whereby, as Hillowe explains, “the feelings the patient had or wanted to have toward a parent become transferred to the therapist, without the patient exercising judgment as to whether the therapist is worthy of such trust.”

WHATEVER O’DONNELL learned in his studies would have added to a gift he already had—inspiring confidence among both kids and adults. In his early days as a priest in Spokane, he was picked by the Spokane diocese to serve first as the associate director, then the acting director, of the Catholic Youth Ministry. The Boy Scouts regional council put him on its board, and the Spokane Police Department had him as a chaplain. Wherever he went, by all accounts, he developed a large following of kids. His two years at St. Paul’s in Seattle, from 1976-78, were no exception. Jim Biteman, a youthful-looking man with a goatee and slightly spiky brown hair, remembers those years. He says O’Donnell got to know him and other boys from the parish school by offering to teach them racquetball at the athletic center at Seattle University. Afterward, the priest would shower with the kids, according to Biteman. “That was part of the deal with him.”

Soon, Biteman says, O’Donnell was taking small groups of boys for sunset cruises on Lake Washington in a 35-foot boat that he kept moored at a Rainier Beach yacht club. “He would make a suggestion that it was a nice night for a swim. Of course, nobody had brought their swimsuits. He would tell us to go completely naked. He would sit in the back of the boat and encourage us to jump in and get out, jump in and get out.”

O’Donnell became a friend of Biteman’s family. Biteman says that one night, when he was in eighth grade, the same year that O’Donnell was pulling him out of classes for “research,” the priest came to Biteman’s house for dinner. Tired, Biteman says he retired early to his bedroom, only to hear O’Donnell knock on the door sometime later. “He came in and sat on the edge of the bed and asked if he could give me a massage.” In the course of the massage, Biteman says, the priest briefly fondled him. Biteman says he was stunned and quickly rolled over. He says the incident was not repeated, and he didn’t tell anybody until other alleged victims started coming forward in recent months.

Meanwhile, O’Donnell’s psychological studies (through UW’s education, rather than psychology, department) were proceeding apace. In the fall of 1977 and early in 1978, he did a six-month internship at the Highline-West Seattle Mental Health Center, where he counseled both kids and adults, dealing with issues including preadolescent and adolescent problems, according to his application, which is on file with the state psychological board. A glowing letter of recommendation by his supervisor there noted his skill at “setting appropriate therapist-client limits on the therapeutic relationship.”

In August 1978, he received his doctorate. O’Donnell returned to Spokane with a clean bill of health from his Seattle therapist, who nonetheless recommended continued treatment to prevent a relapse, according to the Spokane diocese.

It would be surprising if O’Donnell had indeed been rehabilitated, given what we know about pedophilia. “It is considered to be extremely difficult to cure,” says psychologist Hillowe, explaining that such sexual proclivities are deeply entrenched. The Spokane diocese, however, was confident enough to give him a new position as a priest, while sending him to a local therapist it frequently used for clergy. At the same time, O’Donnell worked as a therapist at a family-counseling center in Spokane.

IN THE FALL OF 1979, O’Donnell applied for a state license as a psychologist. Should the Department of Licensing, which preceded the Department of Health as the regulatory agency for the profession, have ferreted out O’Donnell’s disturbing background? “Certainly, the profession does everything it can to screen out everyone with risk factors,” says Douglas Wear, executive director of the Washington State Psychological Association. He points out that by the time candidates apply for a license, they have gone through the rigorous process of getting into a doctoral program and have been subject to “a great deal of scrutiny” in pre- and postdoctoral work experiences.

O’Donnell supplied more than one enthusiastic letter of recommendation from those experiences. Supervisors from the Spokane counseling center where he worked wrote that he was “a credit to the profession of psychologist” and that he “rates among the very best.” O’Donnell passed oral and written licensing examinations, though he failed the written test the first time. A scrawled note on the evaluation sheet of one oral examiner is a testament to O’Donnell’s way with people. It read, simply, “a real charmer.”

True, the application process at that time might be considered lax by today’s standards. Applicants did not have to fill out the one-page form used today, which asks if they have any relevant medical conditions and whether they have ever been treated for pedophilia. (Such self- disclosure, obviously, is far from fail-safe, and even a yes answer to those questions triggers an individual evaluation rather than automatic disqualification.)

Nor was there a criminal-background check when O’Donnell applied, as there is today. But even if there had been, it would have turned up nothing, because he had no record of involvement in criminal proceedings.

The state could be reasonably excused for failing to detect anything amiss in an application by a candidate who was entitled to call himself “a priest in good standing” and whose supervisor was the bishop of Spokane. The state’s subsequent actions are much harder to fathom.

In 1984, a complaint came to the Department of Licensing about O’Donnell’s behavior with two 13-year-old boys on a boating trip four years prior. They were not patients, though O’Donnell had become a licensed psychologist only months before. A disciplinary committee convened by the department investigated. Its findings of fact are reminiscent of the episode described by Biteman. Late at night in the sleeping area of a cabin cruiser, O’Donnell offered to massage the two boys—and ended up fondling them until the boys rolled over. The next day, he took a swipe at one of the boy’s bathing suits while wrestling, and O’Donnell went nude himself while the boys watched him swing over the water and drop in.

“The taking of indecent liberties with a person less then 14 years of age is a class B felony,” noted the disciplinary committee in its findings of fact. Yet the disciplinary committee made no mention of referring the case to prosecutors as it issued only a temporary sanction: a deferred suspension while, for two years, O’Donnell was to practice under supervision and to refrain from unsupervised contact with boys younger than 17.

Such a sanction, at first, sounds stricter than it was. Then, as now, a supervisor was merely required to review case files periodically, not to be on hand during sessions with patients.

At the end of O’Donnell’s two-year sanction, he was free to resume his practice as before. Like others in his field, Long Island psychologist Hillowe questions the wisdom of such a short sanction for a reputed pedophile. “Before someone like that should be allowed to practice, I would have to have evidence of some radical transformation,” he says.

Curiously, one of the three members of O’Donnell’s disciplinary committee, Anacortes psychologist Carroll Meek, now says she also finds the sanction inadequately short, though she has no recollection of how it was determined. “The information I had at the time was that people who have that type of condition do not change,” she says, although there was disagreement in the field at that time.

AS RECENTLY AS 1994, more information about O’Donnell’s background was brought to the attention of the state’s regulatory agency, now the Department of Health’s psychology board. A Spokane mother and former parishioner of O’Donnell’s wrote a letter after hearing, to her amazement, that O’Donnell was still practicing in the state as a psychologist specializing in children. (Such a specialty is not confirmed by other documents; O’Donnell is described in the 1984 findings of fact as treating families as well as individuals.)

The woman, whose name had been removed from the record released to Seattle Weekly, described how, while still a parishioner of O’Donnell’s at St. John Vianney near Spokane, she and other families there discovered why and how their priest had been disciplined by the state. Even after that process became part of the public record, O’Donnell had continued to work as a priest as well as a psychologist. As the families investigated further, she wrote, they learned of inappropriate behavior at their church, too: “The Parish Hall showers, which had been broken for 10 years, were suddenly fixed, and Pastor O’Donnell was showering there with the boys.” The priest, she wrote, had also invited a mentally disabled boy to go boating with him, causing the families to worry about a repeat of earlier behavior.

The woman wrote that the concerned families met with higher-ups at the diocese, including the bishop, to voice their concerns. The diocese seemed supportive of O’Donnell, she wrote, but he soon left the priesthood.

Eloquently, the woman expressed her thoughts about the fact that O’Donnell remained a psychologist: “Again he has managed to move himself in a position of trust to vulnerable youth. Again he has been given the opportunity to create the perfect setup for self-gratification without any compassion with (sic) the families and children who entrust him with their feelings, emotions and future.”

A glaring red flag, you would think, and one that offered numerous possibilities for follow-up. The woman invited a phone call, including her home and work phone numbers. She said there were others the psychological board could question—for starters, the bishop. The board had a unit of trained investigators at its disposal that could look into the matter, the same unit that is now investigating O’Donnell. What the board did in 1994, though, was wait two and a half months to respond with a letter to the woman that put the onus on her to supply names, dates, and witnesses. When that and two other letters the state sent her went unanswered, the matter was dropped.

Why didn’t the board at least call the woman? “I typically did not call,” says Terry West, the board’s former program manager, now an administrator with the nursing unit of the Department of Health. “It’s real hard to second-guess so many years later.”

A memo in O’Donnell’s file, however, shows that the board did consider another avenue. Written by a Department of Health attorney, the memo says it would be possible to draft a statement of charges against O’Donnell based on public-safety grounds—in other words, not on specific transgressions but on those that he might commit in the future. The memo adds, “Since such a prophylactic use of the [Uniform Disciplinary Act] would be controversial, the case should be carefully reviewed to decide the level of commitment and resources to be devoted to such an approach.”

The decided level of commitment and resources apparently was zero. O’Donnell continued his Bellevue practice unchecked.

THERE IS NO evidence that the board’s inaction had negative consequences. Nothing was heard again about O’Donnell until his story blew up in Spokane a few months ago, when alleged victims from his past came forward. Some can’t help but wonder if O’Donnell has used his second profession to abuse. “As prolific as he was [at abusing kids] in his capacity as a priest, it seems unlikely to me that he all of a sudden stopped,” says Michael Corrigan, a Spokane writer who is one of the plaintiffs. No doubt, the truth will emerge as the story continues to unravel.

Yet even if O’Donnell’s behavior has been exemplary for at least the past 15 years, one must wonder: If a reputed pedophile is allowed to remain a psychologist—not once but twice—who else is slipping through?

The Rev. Patrick O’Donnell

Born: Oct. 20, 1942, Quincy, Ill.

1958-1967: Boy Scouts camp counselor.

1964: Bachelor of arts in psychology, Gonzaga University, Spokane.

1965-1967: U.S. Army Medical Service.

1970: Master of arts in counseling and guidance, Gonzaga University.

1971: Master of divinity, St. Thomas Seminary, Kenmore.

1976: Sent to Seattle for sexual-deviancy treatment, where he was appointed to St. Paul’s parish.

1978: Internship, Highline-West Seattle Mental Health Center.

1978: Ph.D. in counseling psychology, University of Washington. Dissertation: “Evoking Trustworthy Behavior of Children and Adults in a Prisoner’s Dilemma Game.”

1979-1980: Therapist, Family Counseling Service, Spokane.

1980: Licensed as a psychologist by the State of Washington.

1984: State Department of Licensing defers suspension of psychology license after finding he committed “grossly immoral acts” involving two 13-year-old boys in 1980.

Mid-1980s-2002: Private practice psychologist, Bellevue.

1994: State chooses not to pursue another complaint that cites O’Donnell’s history.

2002: O’Donnell and Spokane diocese sued by alleged victims, now adults.

SOURCES: Washington Department of Licensing, the Roman Catholic Diocese of Spokane, personal r鳵m鮍