GENE(SIS)

Henry Art Gallery University of Washington 543-2280, $6 11 a.m.-5 p.m. Tues.-Wed., Fri.-Sat.; 11 a.m.-8 p.m. Thurs. opens Sat., April 6

IN A STUDIO NEAR the International District, artist Jaq Chartier is conducting another experiment. Clad in a paint- spattered T-shirt and jeans, she eyes her work: row after row of green, pink, and blue blobs. Over the past several days, these colorful ink spots have begun to appear from underneath layers of opaque white varnish, like spring flowers emerging from snow.

Some of the spots are covered with masking tape, while others have been exposed to the late-winter sunlight. Chartier inspects one series of blobs created with a pink dye—the kind used by biology students to stain microscope slides. She’s penciled her observations in the margins. One dot in particular catches her attention: a blemish that’s curdled and broken into a pattern resembling an amoeba.

She smiles. “That one’s doing something really cool.”

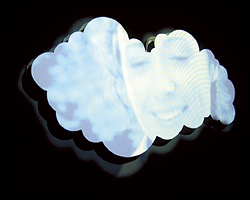

A technician of sorts in her makeshift laboratory, Jaq Chartier has turned the mixing and observation of pigments, inks, and dyes into an art form. The Seattle-based painter has found in the biosciences both a method and a language for the exploration of color. Hanging on the walls of the studio are the results of her experiments: gorgeous abstract paintings composed of blurry dots. What these paintings most resemble are the results of gel electrophoresis—DNA tests used to identify crime suspects and map the human genome.

This affinity with genetics has earned Chartier a place as one of two local artists in an ambitious new exhibit opening next weekend at the Henry Art Gallery called “Gene(sis).” Through art installations, dance, panel discussions, and film, the Henry will examine ethical issues related to cloning, genetic engineering, gene mapping, and DNA ownership.

The two dozen artists showcased in “Gene(sis)” present a wild variety of approaches, from Christine Borland’s HeLa installation—complete with microscopes and actual live cell cultures—to the bioscience-critical cartoons of Tom Tomorrow and Roz Chast. Chartier’s art is more obliquely connected to the subject. “My work really isn’t about DNA or science. It’s just kind of bouncing off it,” she says. Although Chartier intuitively incorporates the imagery of DNA science into her paintings, it’s her method—a kind of hybrid of artistic and scientific endeavor—that makes her work most relevant to “Gene(sis).”

Chartier’s paintings reduce the artistic process to its most elemental: What happens when a painter applies a material, in solution, to a surface and lets it dry? We’re often reminded of how divergent science and art are; Chartier manages to bridge the gap between the two realms.

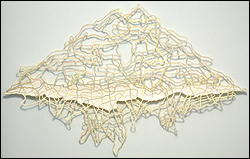

Another rigorous experimenter in materials, Susan Robb, is the other Seattle-based artist represented in “Gene(sis).” But Robb’s photographs and installations make use of a more outrageous palette: spit, moss, glass cleaner, urine, Play-Doh, and melted chocolate rabbits, to name a few. Chartier, by contrast, is a painter first and foremost.

MUCH IN THE SAME way that Alexander Fleming accidentally discovered the antibiotic properties of penicillin in his lab sink, Chartier stumbled upon her m鴩er in a seemingly banal place. While working as an instructor for an acrylics company, Chartier was always testing materials. She soon realized that the tests she’d created were more interesting than her paintings.

The paintings themselves have now become an active record of those tests: studies in how different pigments migrate and fade in reaction to other materials, sunlight, and the passage of time. Sometimes, the materials change in surprising and beautiful ways. Other times, they look bizarre or awkward. No matter: Chance and chaos are essential elements of Chartier’s work. “I need the accidents to happen to keep me interested,” she says. “If I know what’s going to happen from start to finish, I get bored. For me, making the painting is finding the painting. I want to be surprised by it.”

When she first learned about gel electrophoresis during the O.J. Simpson trial, Chartier began amassing a sizable scrapbook of biology images: pictures of mold, blood cells, and botched DNA tests. Chartier says she hasn’t yet visited a working biotech lab—she’s afraid that knowing too much will make her work too literal.

Instead, a friend who works for a biotech company regularly e-mails Chartier material. “She sends me all these JPEGS: things that, because they made a mistake with the gel, gave them a weird artifact. Now all the stuff they throw in the trash, they’re starting to look at again. They’re starting to see what they’re doing as art.”

Cynics might argue that this is exactly the audience Chartier is targeting: wealthy biotech companies that would love to put pretty paintings resembling DNA tests on their walls. This point isn’t lost on the artist or the William Traver Gallery, which represents her. Recently, Chartier sold a painting to Immunex, and she hopes to sell more to a Canadian biotech researcher. “I think it’s a great fit,” she admits.

But watching her at work in the studio, it becomes clear Chartier isn’t merely interested in becoming the region’s next Chihuly, churning out profitable candy for the walls of corporate lobbies. There’s a real integrity to her curiosity, a painstaking fascination with migration of inks that brings to mind Mark Rothko’s investigations of color 50 years ago.

“I’m really obsessed with the bleeding edge on a dot,” she says. “Putting a dot of oil paint down on a piece of paper and having that edge of oil soak out and leave this ring. There’s something about that edge. It’s one of those weird obsessive things that would be minutiae to anyone else.”