THE WONDERBRA HOOPLA of the mid-’90s was probably the biggest snow job ever pulled off on lingerie-hungry women. Even though its manufacturer Sara Lee (the corporation which brings you everything from pound cake to Coach leather products) convinced bustline-deficient women that it had invented the Last Word in boob inflation, the exact same bra had been on the market for 20 years. Furthermore, any bra company worth its salt had been selling push-ups years before the Wonderbra publicity fracas, replete with its arrival, in an armored truck, at Macy’s in New York City.

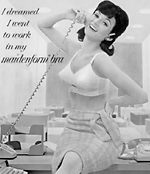

According to Katie Kretschmer, editor of BFIA (Body Fashions/intimate apparel), a trade magazine for the intimate apparel industry, here’s what really happened: A Canadian company called Canadelle actually invented the Wonderbra in the ’60s. Sara Lee later bought Canadelle, and Canadelle then licensed the manufacture of the Wonderbra to Gossard, a firm in the UK. When that license expired, Sara Lee took it back and relaunched the Wonderbra as the first and last word in bust enhancement—even though our sisters to the north had been in the know for decades. But the notion of “lift and separate” is not as old as you might think. In fact, the bra is a 20th-century invention and a damned good example of the “necessity is the mother of invention” maxim. A quick lesson in fashion history helps explain why this item women take for granted was such a late bloomer.

1910: Corsets had long done the trick of pushing up the bustline from below, until fashion started to become less restrictive in the 1910s. As the hourglass and monobosom silhouettes lost favor, the corset became obsolete. The burning question then became: How does a gal fight gravity?

1920: For some, it wasn’t much of an issue. By the early ’20s the flapper look was in vogue. Women were adopting looks that diminished the differences between the sexes. Long hair was out and the bob was in. The bright young things actually wanted to flatten their busts. In order to squelch nature’s inclination for outward expansion, they wore tight-fitting bandeaux, which were essentially strips of fabric, embellished with lace depending on the buyer’s budget. (The Boy’sh Form Bandeau, for example, made no bones about its breast-banishing purpose.)

But some forward-thinking New Yorkers were having none of that. Enid Bissett and Ida Rosenthal were partners in an exclusive Manhattan dress shop. In 1922 Bissett believed that the boyish look was on its way out, and she wanted to create an undergarment that would allow dresses to fit better over a woman’s bustline. She reshaped a bandeau so that it had two cups separated by a center piece of elastic. Rosenthal’s husband William got in on the act (not how you’d think). He put some finishing touches on her creation, transforming it into an attractive garment shaped to support the breasts’ natural contours. Voila! The first Maidenform brassiere.

These early bras lacked the seams and construction that shape and support in the manner to which women have become accustomed. They were made from relatively ethereal fabrics—silk chiffon, cotton net, and lace—that do little in the way of molding and shaping when compared to today’s Lycra-enhanced fabrics.

The notion that a bra could provide uplift was not introduced until William Rosenthal (who, as president and chief designer of Maidenform for decades, was recognized as one of the bra industry’s consistent design innovators) received a patent for the first seamed uplift brassiere in 1927. This novel garment featured a three-seamed cup, which created more uplift and definition to each breast.

1930: By the ’30s the notion of two naturally separated breasts was the norm, and cotton, considered the far more supportive fabric, was commonplace. In 1935, the Warner Company introduced the cup system.

1940: The notion of uplift reached its zenith in the late 1940s with the introduction of a highly constructed bra, which has been dubbed the bullet bra, torpedo bra, cone bra, etc. You know, the spoked bra you find in vintage stores or in grandma’s attic. Call it what you like, it created the bust silhouette from the late ’40s and through much of the ’60s.

Anyone who thinks bra design is simply a matter of prettily assembled laces and fabrics should take a look at the highly engineered design of a bullet bra. Due to its spokelike construction and reinforced rows of concentric lock stitching, this style produced the thoroughly artificial breast shape associated with the hubba-hubba stars of the period: Lana Turner, Jane Russell, Marilyn Monroe. No, their boobs really weren’t that perky—it was the bra. Perhaps it’s just coincidence, but consider the fact that this missile-like garment was designed and worn during the Cold War, creating an at-the-ready silhouette similar to the shape of a radome (otherwise known to civilians as the nose of a plane). The result: in your face sexuality, literally and otherwise. These breasts were impossible to ignore, declarations of highly stylized femininity, and most likely an extension of the period’s fascination with the shapes and contours found on cars and planes.

Wearing a bullet bra was definitely an exercise in control. Some women ironed these cotton broadcloth brassieres to eliminate distracting wrinkles and to insure a picture perfect point; others bought pads to insure that their points were indeed points and not just forlorn little puckers.

1950: With the advent of strapless dresses in the late ’50s, strapless bras were soon called for. Enter the underwire. Ask any woman who went to a prom in a strapless evening dress around 1959 and you’ll get an earful—stories abound about dire pain around the rib cage and emergency readjustments in the powder room. That’s because the early underwires were actually made from metal, rather than today’s infinitely more flexible and comfortable plastic components.

1960-1970: Underwires—and sometimes bras themselves—went out the window by the early 1970s, as women adopted a more natural look. For those who could go braless, this was the moment of let-it-all-hang-out glory. Young people eschewed any sign of constriction in clothing, so the highly structured bullet bra quickly became dated. For those whose breasts required support, seamless bras that created a rounded, natural no-bra look became popular.

1980: The ’80s brought yuppie excess to the cultural forefront, and lingerie was no exception: Satin and lacy concoctions evolved at a time when more and more women were entering the professional workplace, and ads were full of escapist, romantic imagery. But there was also a strain of practicality. The “Should we dress like men for business?” question (which launched the silly woman-with-tie-and-briefcase look) extended to the underpinnings department. Hence, the advent of Jockey For Her underwear, and numerous imitations. Lingerie of the late ’80s began to shift toward the idea of expressing power through sexuality and the display of a well-worked-out physique.

1990: Hello to Victoria’s Secret, which in tandem with the Wonderbra’s popularity in the mid-’90s, has transformed lingerie from a relatively private, girls-only discussion topic to something worthy of hour-long specials on E! Entertainment Television and the “innerwear as outerwear” trend which continues today.

The latest lingerie gimmick is the Water Bra from Fashion Forms, which is padded with a water and oil cookie (the industry term for the pads that create the oomph in a push-up bra) that aims to look and feel like the real thing.

Size Matters

We see you on the bus, trying in vain to scratch the middle of your back, subtly shrugging that strap back up, looking somehow a little pinched, perhaps even vexed. We feel your pain, and we have a name for it: Bra Tension. In the interests of eradicating this scourge, we sent an intrepid Seattle Weekly reporter to a Certain Large Department Store to be officially, professionally Fit. She reports:

*You, yes you, are wearing the wrong size. Everyone is, unless for some reason you’ve actually been fit as an adult, which is rare. As the charming Lingerie Specialist put it, “We all got fit once in junior high by the woman with the cold hands at Frederick & Nelson’s and never looked back.” Now is that any kind of prescription for undergarment happiness? I was wearing the wrong size in two different dimensions! The mind reels!

*You need professional help. If you’re going to bother to wear a brassiere, that is. Yes, this involves partially disrobing in front of a stranger, but think of her as the Bra Doctor. My Bra Doctor said, “Take off your shirt,” in such a straightforward, clinical manner that I obeyed without thought, any embarrassment taking flight in the face of such a serious sizing endeavor. Your rib cage will be measured. Your Bra Doctor will deploy specific brassiere terminology in assessing the fit of various possibilities. She will knock lightly prior to coming into the dressing room—each time. As mine put it, “It’s kind of weird being naked in front of a stranger, but we try to make it no big deal.” Mission accomplished.

*You should try on lots of different models. They have a bra for everyone, and for most people many styles that will accomplish your bosom’s desire: minimize, maximize, bring them up just under your chin. I got a neat new kind called “balconette.” Where do they come up with these things? They must be in cahoots with the people who name cars.

*You had better be prepared to shell out. A mid-range bra at Certain Dept. Store costs about $35. The women of Lingerie will not hard-sell you, but I wanted three bras and, what the heck, some skivvies (another good thing to consult about: “There’s a lot of angry panties out there,” my professional said, also asking me how tall I was to get the right size!), so there went $200. Trust me, my friends: The banishing of Bra Tension is worth it.

Clare McClean is a Seattle-based freelance writer and former director of the Maidenform Museum in New York City.